About the Authors

Chris Brown is the Director of Policy and Research with Common Sense Institute where he leads the research efforts of CSI to provide insightful, accurate and actionable information on the implications of public policy issues throughout the state of Colorado.

Abigail Giannou is a Research Analyst with Common Sense Institute where she supports the research efforts of CSI. Abigail is going into her senior year at University of Colorado Denver. She is studying International Business with a minor in Economics.

Bella Lawrence is a Research Analyst Intern with Common Sense Institute where she supports the research efforts of CSI. Bella recently graduated from Colorado College in 2020 with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in History.

About Common Sense Institute

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

Executive Summary

At the November 2020 election, Colorado voters approved Amendment B, a constitutional ballot measure which repealed a key formula that has controlled the state’s property tax system for almost 40 years.

In the short term, passage of Amendment B has frozen Colorado’s current system in place. However, it is possible – if not likely – that further reforms will be proposed and debated in the years to come. With this in mind, a logical place to start these discussions is by reviewing how Colorado’s property tax system compares to the systems in place in other Western states.

In this study, the Common Sense Institute (CSI) conducted a detailed review of the following seven state property tax systems: Colorado, Arizona, California, Idaho, Texas, Utah and Wyoming.

Further, the analysis looks at each state across six critical areas of property tax policy.

- Are Property Tax Rates Determined at Local or State Level?

- Does Each Type of Property Pay Equivalent Tax Rates?

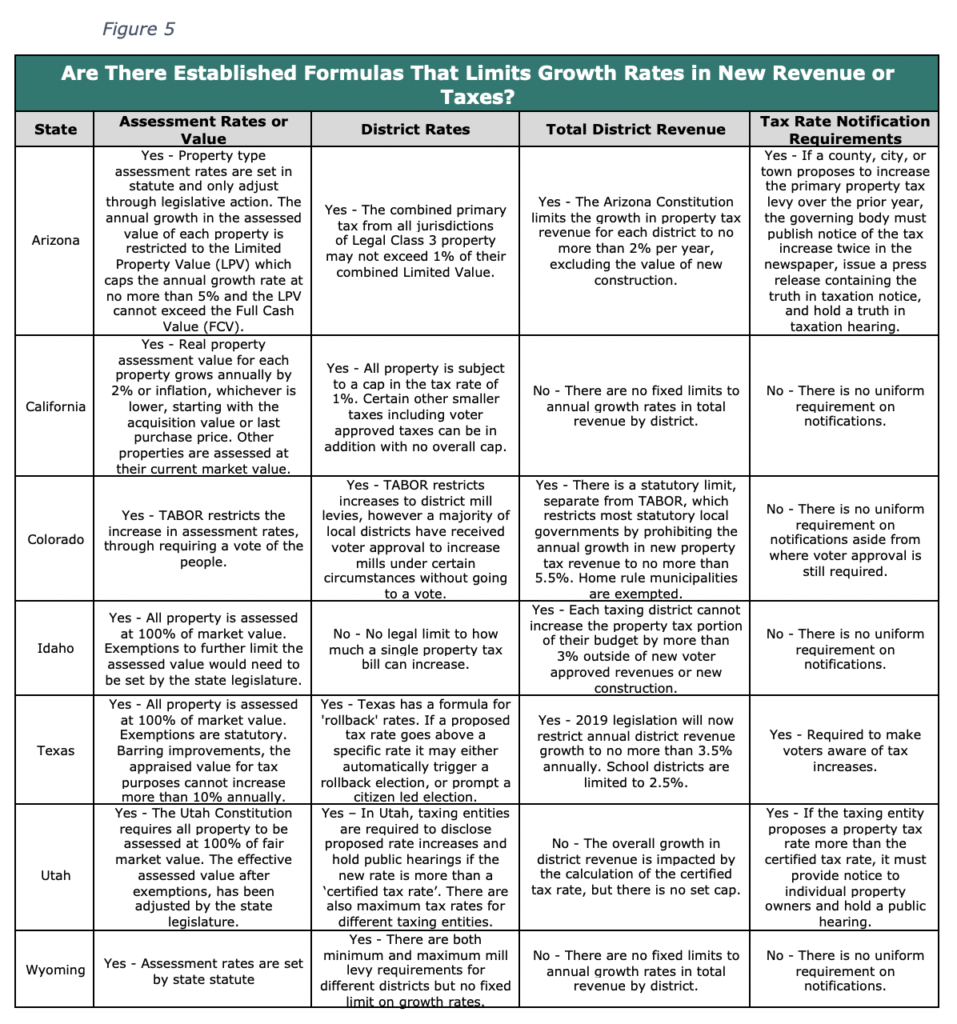

- Are There Established Formulas That Limits Growth Rates in New Revenue or Taxes?

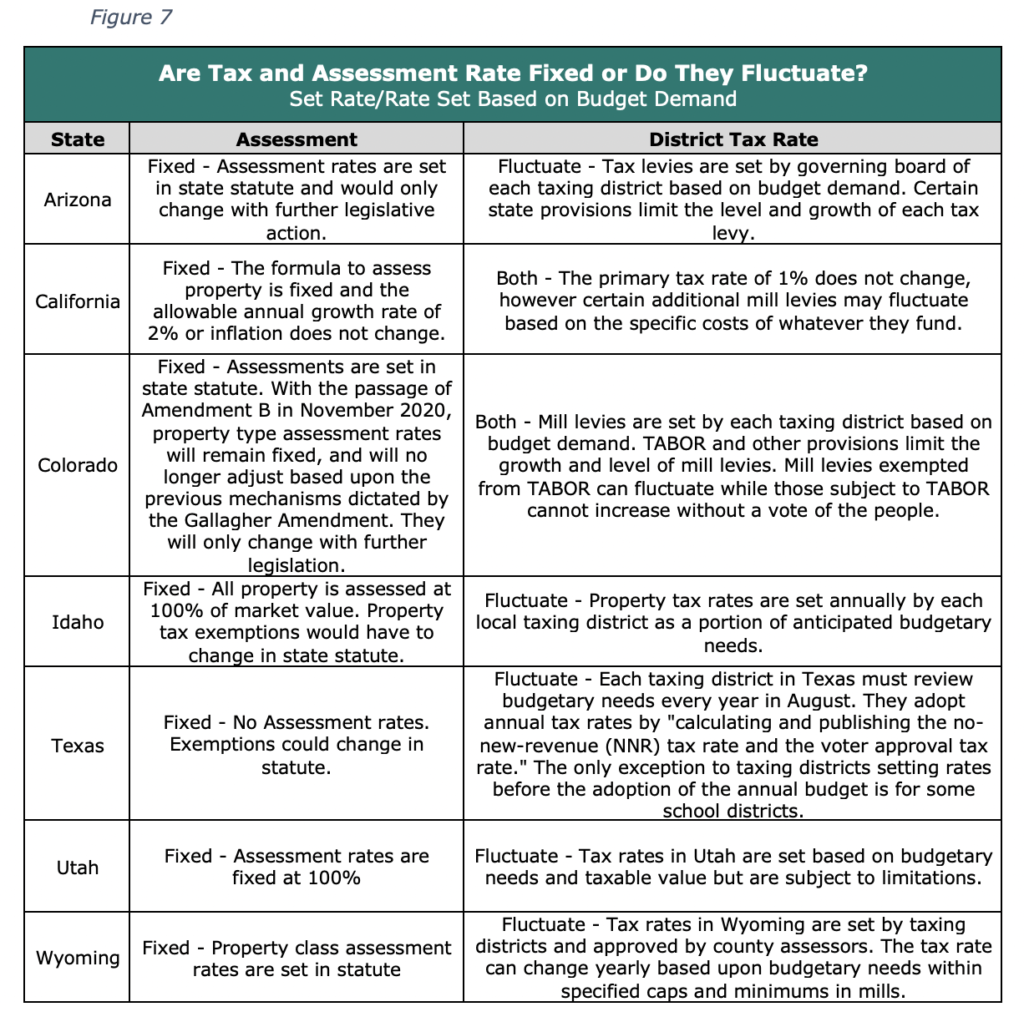

- Are Tax and Assessment Rates Fixed or Do They Fluctuate Based on Budget Demand?

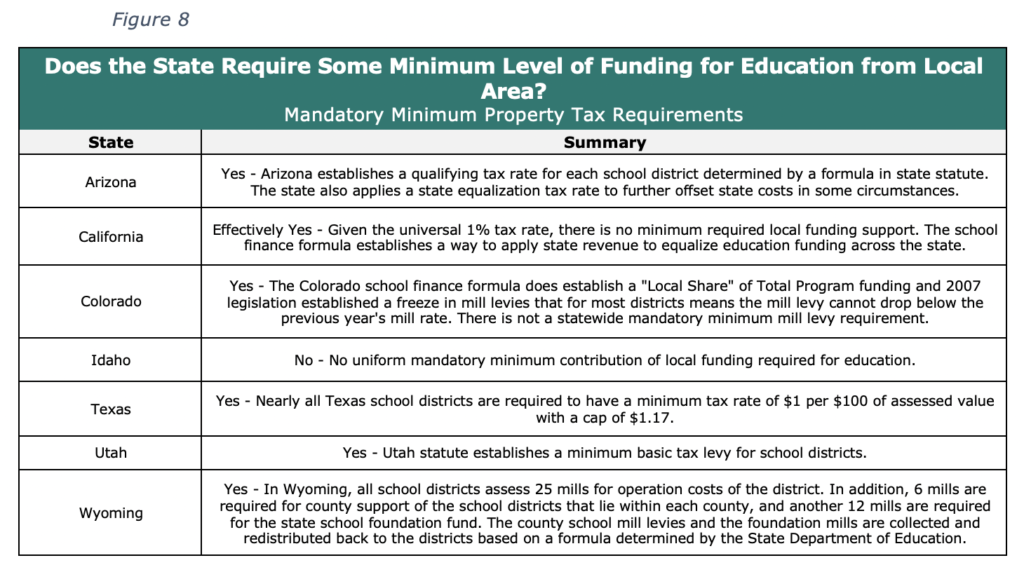

- Does the State Require Some Minimum Level of Funding for Education from Local Area?

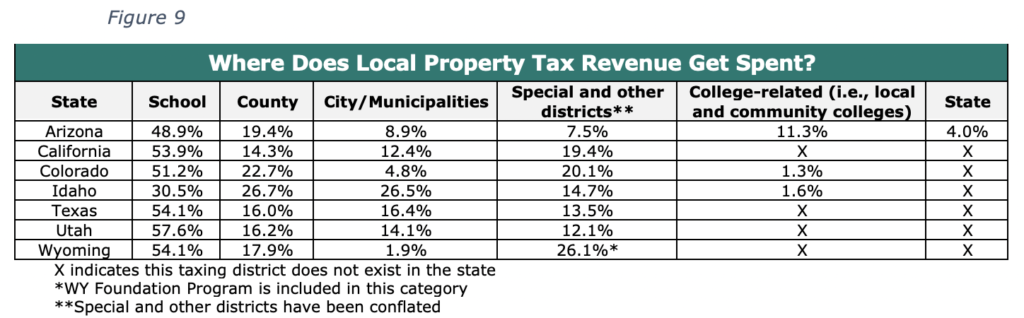

- Where Does Local Property Tax Revenue Get Spent?

While there are many points of similarity along with major differences across these 7 states, some key findings include:

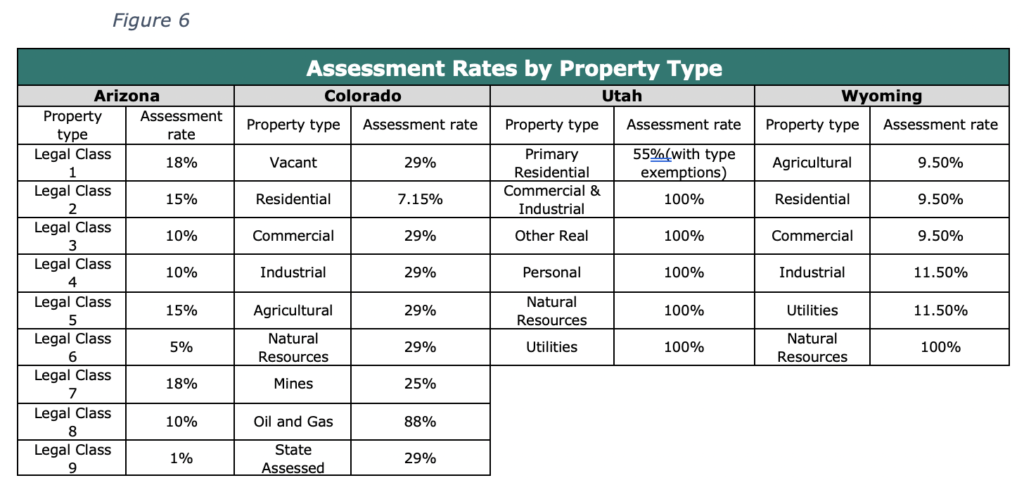

- Each state taxes different types of property (e., residential, commercial, agricultural, mineral etc.) at different effective tax rates. This is done through establishing different assessment rates across property types, or through the offering of exemptions that partially or wholly exempt value of certain property types from taxation.

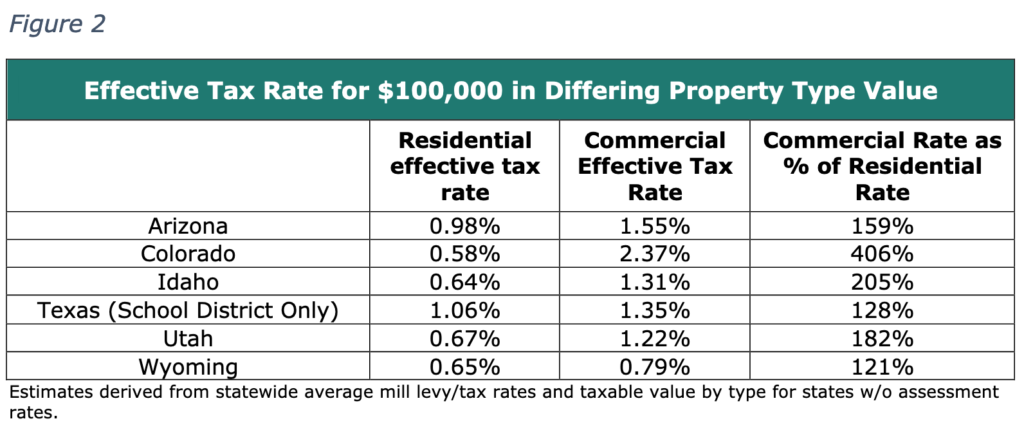

- In Colorado, the state property tax assessment rate for commercial property is 300% – e., 4 times – higher than residential property. This is the widest margin between commercial and residential property tax assessment rates observed across all seven Western states examined in this study.

- By comparison, Arizona and Utah have the next widest margin – roughly 80%, less than 2 times – between state assessment rates for commercial property and residential property.

- Three states – California, Idaho and Texas – do not set different statewide assessment rates for different classes of property. However, a number of exemptions exists that result in a lower effective tax rate for residential property than other property classes.

- Out of the seven states studied, only Texas gave local governments explicit flexibility to adjust assessment rates for different classes of property through exemptions. Under Texas law, these local exemptions are limited to 20% or less of a property’s market value. As a result, the taxable value of single-family residential property, including individual exemptions, is 78.1% of market value within Texas school districts.

- All of the seven states studied limit the growth in property taxes through one or more restrictions, including tax rate caps, revenue caps, annual growth restrictions or taxpayer notifications.

- With the exception of Idaho, all of the states studied require a minimum level of local property tax revenue to be dedicated towards public education.

- While all states have some form of special taxation districts, Colorado has the highest percentage of revenue going towards special districts, which provide a range of services including fire protection and water and sewer infrastructure.

These observations suggest that even after the passage of Amendment B, further structural reforms are likely to be pursued by state policymakers and taxpayers.

While some components of Colorado’s property tax system are largely consistent with those of other Western states, other components continue to be out of step. To be certain, it may be argued that some of these differences produce competitive advantages for our state economy, businesses and working families. However, there may also be competitive disadvantages that result in Colorado losing jobs and investment to other Western states, among other negative economic impacts.

No matter where individual policymakers, constituencies or citizens stand on the issue of property taxation, the outcome of this debate is too important to leave to chance. Given the pivotal role that property taxes play in supporting essential services in our state, it is essential that the debate over potential reforms be guided by the facts. This study aims to start the discussion on the right path.

Introduction

For the first time in almost four decades, Colorado voters have approved a major reform in the way property taxes are assessed. In the November 2020 election, by a margin of 57.5% to 42.5%, voters passed Amendment B, removing a key formula from the Colorado Constitution which had controlled the state’s property tax system since 1982.

The 1982 formula, known as the Gallagher Amendment, applied a fixed ratio to the amount of revenue collected from residential and non-residential property classes. However, over the course of almost four decades, the amount and value of residential property in Colorado grew much faster than all other property classes.

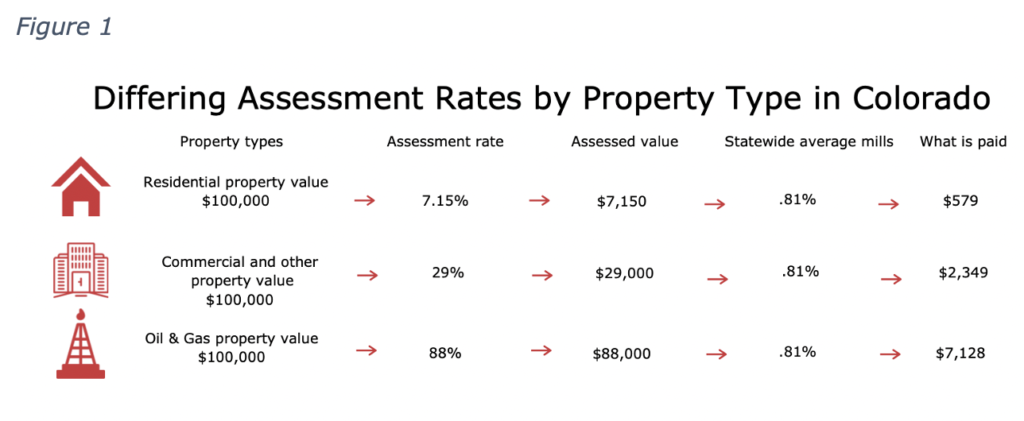

To maintain the fixed ratio, the share of residential property subject to taxation in Colorado was automatically lowered by the Gallagher formula, from 21% in 1983 to 7.15% in 2020. However, the Gallagher formula kept the share of non-residential property subject to taxation fixed at 29% over the same timeframe, which produced a number of unintended consequences.

One of which was a major increase in the relative property tax burden for non-residential property classes, including restaurants, retail stores, office buildings, industrial parks and agricultural land. In 1983, for example, the Gallagher formula required that an average business pay 38% more in property taxes than a residence of the same value.

By 2020, however, the Gallagher formula set business property tax rates four times higher than residential property tax rates. Moreover, if Amendment B had failed and the Gallagher formula remained in effect, it was estimated that business property tax rates would increase again in 2021 to almost five times the residential level.

Another result of the Gallagher formula was reducing the size of the local tax base in many communities, particularly in rural Colorado. This was a major concern because property taxes are a critical source of funding for K-12 schools, fire departments, hospitals and many other essential services at the local level. In 2019, for example, property taxes generated more than $11 billion in revenue across Colorado, which is more than the state generates from personal and corporate income taxes combined.

For this reason, the Gallagher formula was viewed as a threat to local budgets and a major source of uncertainty for local communities. For example: before the passage of Amendment B, a coalition of state and local business groups estimated more than $650 million in cuts to local services in 2021 due to the Gallagher formula. It also created a growing burden on the state budget through education funding requirement. Two credit rating agencies, Moody’s and Fitch, both indicated that the passage of Amendment B was a positive for the state’s credit rating given that less state funding would likely be needed in future to backfill education expenses.[i][ii]

In connection with Amendment B, state lawmakers approved a moratorium on changes to statewide assessment rates – SB20-223. In effect, this means statewide assessment rates – which determine the percentage of a property’s value that local governments, school boards and other special districts are allowed to tax – are now frozen at their current levels in Colorado: 7.15% for residential property and 29% for most other kinds of non-residential property.

Going forward, changes to assessment rates would require statutory changes initiated by either the legislature or at the ballot. Due to the TABOR provisions of the Colorado Constitution, any increase would require approval from voters. Therefore, at a minimum, the repeal of the Gallagher formula and the moratorium on changes to statewide property tax assessment rates will stabilize the state’s property tax system – and the services funded by property taxes – at least in the near-term.

At the same time, however, the passage of Amendment B is likely to spur further discussion and debate over more improvements to the Colorado property tax system beyond the current freeze in statewide assessment rates. For example: The advocacy group Colorado Rising State Action has proposed an initiative for the 2022 ballot which would reduce the residential assessment rate to 6.5% and the commercial assessment rate to 27%.

In short, lawmakers and voters may soon be asking themselves: Is the current system satisfactory or are there better alternatives? Through this study, the Common Sense Institute seeks to inform discussions over the future of Colorado’s property tax system.

Colorado’s Property Tax System: Before and After Amendment B

Colorado property taxes are determined using a two-year cycle process that is partially controlled by the state and partially controlled by local taxing authorities, such as cities, counties and school districts. The amount of property tax due is determined in the following manner:

Before the passage of Amendment B, the assessment rate for residential property – which represents approximately 80% of all property value in Colorado – was variable and depended on the workings of the Gallagher formula. Under the formula, statewide assessment rates could be changed at the start of every two-year property tax cycle, injecting considerable uncertainty into Colorado’s property tax system.

For example, in the 2017-18 and 2019-20 property tax cycles, the Gallagher formula reset residential assessment rates consecutively. If Amendment B had not repealed the Gallagher formula, state officials predicted a third successive reset would have occurred in the 2021-22 property tax cycle. Altogether, these three successive changes in assessment rates could have cut the amount of residential property value subject to taxation in Colorado by 26%, in less than six years.

Today, following the passage of Amendment B, the residential assessment rate is fixed, just like non-residential property. This provides a significant measure of certainty for local communities and other stakeholders, because now there are only two variables in Colorado’s property tax formula – actual values and local mill levies – instead of three. This will likely make budgeting more predictable at the local level and also reduce the need for local mill levy increases. Given the higher assessment rate for businesses, this means property tax increases that have four times the financial impact on businesses for an equivalent value to residential property owners are less likely to occur.

However, the benefits of this stability must be weighed against other potential consequences, including:

Impacts on residential property bills

This issue was discussed at length during the campaign over Amendment B. By keeping the residential assessment rate fixed at 7.15%, instead of allowing future reductions under the Gallagher formula, a relatively larger share of residential property value will be subject to local mill levies than prior to the passage of Amendment B. Therefore, if the value of residential property increases, then it is possible that individual homeowners will pay higher property taxes and see their taxes go up faster than they otherwise might have.

However, it should be noted that local mill levies are not static. They can be reduced by local governments, school boards and other special districts in response to projected revenue increases. In many cases, these reductions are required under TABOR or other statutory limitations. For this reason, discussions concerning potential residential property tax increases should not overlook all the other factors at play besides the fixed assessment rate of 7.15%.

Continued disparity between residential and business property tax rates

Voter approval of Amendment B prevented businesses from paying five times the tax rate applied to residential property. But the current freeze still leaves businesses paying four times the residential rate. In some communities, including Denver and Colorado Springs, this means businesses are paying much higher effective property tax rates than businesses located in major cities like New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco.[iii]

Tension between statewide assessment rates and unique local conditions

There are more than 4,100 local tax authorities in Colorado, including school districts, cities, counties, fire protection districts, metropolitan districts and hospital districts.[iv] Each have distinctive boundaries and a unique mix of residential and non-residential property that contributes to their respective local tax bases.

One of the criticisms against the Gallagher formula was that assessment rates would reset automatically and without regard for the wishes of local communities. This was largely because the Gallagher formula was intended to maintain a fixed statewide ratio for the amount of tax revenue collected from residential and non-residential property classes.

Gallagher’s fixed statewide ratio failed to account for the wide variation in local tax bases across the state. Many local tax districts have a mix of homes and businesses that looks very different than the statewide totals for these property classes. But the Gallagher formula effectively assumed all communities had the same property tax base as the entire state, just on a smaller scale. For this reason, rural communities – which typically have less commercial property than urban and suburban communities and have not experienced the same level of residential property growth as urban and suburban communities – were disproportionately impacted.

While some communities may welcome the repeal of the Gallagher Amendment and the stability this brings, the assessment rates now in place for residential and non-residential property are still statewide in nature. It is possible that with stable statewide assessment rates, the use of local mill levies may give communities sufficient control over their respective tax bases to succeed economically and maintain funding for essential public services.

However, it is also possible that the fixed statewide assessment rates of 7.15% for residential property and 29% for non-residential property may not allow the flexibility that some communities seek when it comes to shaping their own property tax bases.

To be clear, these and other potential consequences may not come to pass, and if they do, it does not necessarily mean that better alternatives will be identified and pursued. However, in the event that policymakers, stakeholders, and the general public decide to review potential alternatives, the discussion may center on a number of structural elements that already exist in Colorado and other Western states.

Property Tax System Comparisons Across Western State

The process for determining property taxes is complex and varies across states. While homes and non-residential properties exist in every state, the tax systems that arrive at the final collected amounts of revenue vary. As Colorado examines potential paths forward, it is important to note that property tax structures across states all have tradeoffs, thus there is no silver bullet.

However, the steps along the way to reach the final tax requirement follow a sequence of related steps that are all similar in each state.

- Define the type of property that is subject to taxation.

- Determine how much of the total value of property is subject to taxation.

- Determine the taxing authorities that are legally able to apply a tax.

- Determine the tax rate charged by each taxing authority.

Along with determining the manner with which properties are taxed, there are also often statutory or constitutional parameters that limit or restrict different aspects of the collection process. Those different areas of limitation include.

- Whether different classes of property are, or can legally be taxed at different rates.

- The amount of annual growth for assessment rates.

- Limitation on growth in assessed values for each property.

- Limitations on growth rates in mills or district tax rates.

- Limitations on growth rates of revenue collection by district.

- Required minimum levels for local tax revenue contributions towards education funding.

While these steps may capture the general process of determining property taxes, the actual manner with which any state actually taxes property is far more complex. The following set of tables outlines several key dimensions to property taxation across seven western states often viewed as competitors or peers to Colorado.

Key Dimensions to State Property Tax Systems

- Are Property Tax Rates Determined at Local or State Level?

- Does Each Type of Property Pay Equivalent Tax Rates?

- Are There Established Formulas That Limits Growth Rates in New Revenue or Taxes?

- Are Tax and Assessment Rates Fixed or Do They Fluctuate Based on Budget Demand?

- Does the State Require Some Minimum Level of Funding for Education from Local Area?

- Where Does Local Property Tax Revenue Get Spent?

Are Property Tax Rates Determined at Local or State Level?

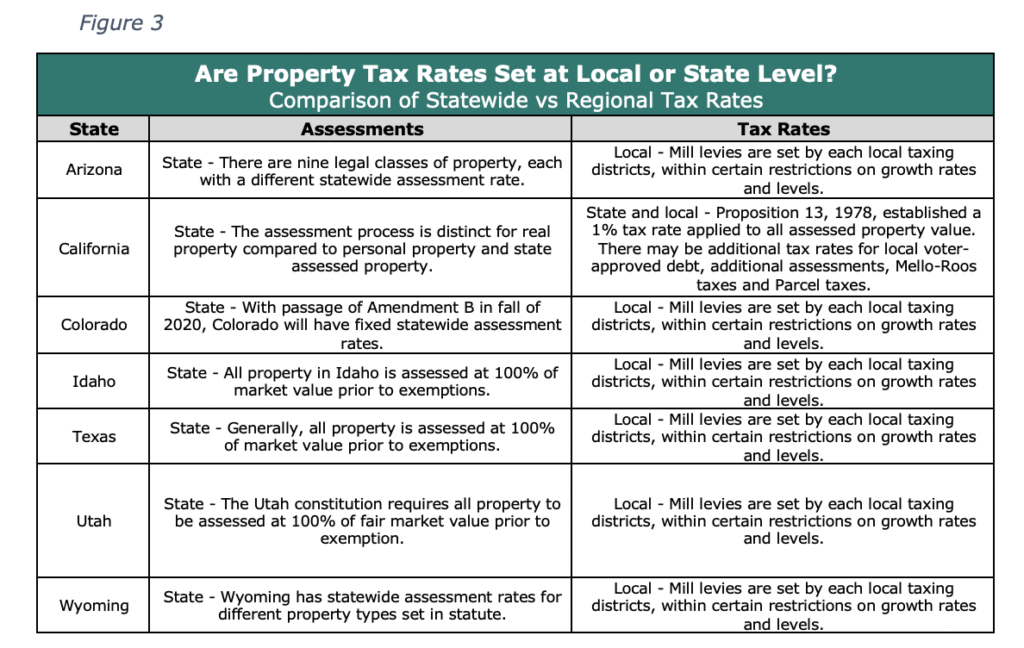

The amount of property tax due for each taxable property is primarily determined by two factors:

- The taxable value of the property

- The sum of all tax rates for districts that cover the property

How these two factors are governed in each state varies slightly, however one important dimension to consider is whether those rates are set by the state or by the local district. Figure 3 gives a summary on the degree to which each of these two aspects of state property taxes are determined by the state or local government.

Key findings

- All seven states have assessment rates that apply uniformly across entire state.

- Six of the seven states studied allows each taxing district to establish their respective mill levy or tax rate within other legal constraints.

- California is only state with a fixed starting tax rate set by the state government. However, the state allows for several other types of voter approved taxes to be applied to local property on top of the base rate.

Does Each Type of Property Pay Equivalent Tax Rates?

Every taxing district charges a single tax rate on all taxable property value within their boundaries. However, it is not always the case that the assessed value of the property being taxed is equivalent to its current market value. Therefore, while each property is subject to the same tax rate from each taxing district, certain properties will have different effective tax rates, as their tax bill will be a different percentage of their market value based on their taxable assessed value as a percent of their market value.

States and local governments lower the assessed value of a property relative to its market value in two ways:

- Varying assessment rates across property types.

- Varying partial or entire exemptions of property value by either class or status of property owner/occupant.

For public policy purposes there may be very legitimate reasons why laws have been created to modify the assessed value of property relative to its market value. As an example, an owner-occupied residential property does not generate an annual income for the owner in the same way commercial property or oil and gas production does. Therefore, whether by changing statute, or through the existence of a set formula, the amount of taxable value relative to market value is an area of property tax policy which changes most frequently.

Figure 4 offers a summary of how assessed value relative to market value differs across states.

Key findings

- Four of the seven states studied establish statewide assessment rates that differ across different property types. The other three states apply some property tax exemptions that establish a difference between the actual value and assessed value of certain property types.

- The largest property type exemption offered in states that assess property at 100% of actual value is for primary residences.

- All four of the states with different assessed rates for different property classes have a lower assessment rate for residential property relative to other property types.

- Colorado has the widest margin between the residential assessment rate and all other property assessment rates. This means that relative to the sum of the market value of residential property, this class provides the lowest relative share of revenue to other property types.

Are There Established Formulas That Limits Growth Rates on Revenue or Taxes?

Along with laws that establish the fundamentals for how property taxes are determined, there are also a set of laws that often establish limitations to the fundamental structure. Often those laws fall under the general category of Truth-in-Taxation laws. While these laws vary from state to state, they generally cover a similar set of limitations intended to improve accountability, transparency and to restrict the growth in property tax revenue relative to the property value.

- Annual growth rates for district tax rates

- Annual growth rates for district revenue

- Annual growth rates in assessed values for individual properties

- Tax rate caps

- Notification of taxpayers on proposed changes to rates

- Voter approval or denial of proposed rates, and voter approval.

Coloradans are very familiar with the provisions of TABOR that limit the annual growth in revenue for both state and local governments and requires voter approval for tax increases.

The interaction of the Gallagher formula and TABOR resulted in a falling residential assessment rate and severe revenue reductions in some parts of the state over the years. As a result, many local property tax districts have received approval from voters to override one, or both limitations of TABOR. Therefore, while TABOR remains an integral part of the state’s constitution, it currently has varying impacts on local property tax decisions.

Key findings

- All states apply at least one limitation to the growth of property taxes across the different possible growth areas.

- None of the other six states reviewed had a similar formula to the repealed Gallagher amendment which maintained a fixed ratio of residential property tax revenue relative to other property classes.

- Colorado and California are the only two states that do not allow tax rates to increase without voter approval. However, most Colorado tax districts have received voter approval to at least partially over-ride this limitation. Many of the voter approved taxes in California can increase based on budget demand without further approval.

- Several states require notification, and public hearings in the event a local tax district proposes a rate increase.

Are Tax and Assessment Rates Fixed or Do They Fluctuate Based on Budget Demand?

The largest components when determining local property taxes are related to addressing the taxable assessed value and the local tax rate. However, how those factors can change differs across states.

Most taxing entities determine their property tax rate by dividing their budget by total taxable value. This means that fluctuation in tax rate can occur based on changes in either the assessed value or budgetary needs or both.

Key findings

- California is the only state with a formula for determining assessed value that starts with the most recent sales price, rather than current market value.

- In Colorado, prior to passage of Amendment B in 2020, the formula established by the Gallagher Amendment stood out for several reasons:

- It was the only formula that adjusted assessment rates to maintain fixed ratios of assessed value across property types.

- It was the only formula that adjusted assessment rates based on changes in value rather than through changes in statute.

- While other limitations apply, California is the only state where the local tax rate is primarily fixed and does not adjust based on local budgetary needs or changes in taxable value.

Does the State Require Some Minimum Level of Funding for Education from Local Area?

All the states evaluated in this report fund public education with both local and state funding, along with other sources. A primary objective of education funding for many states is to “equalize” funding across all parts of the state to ensure all students have similar opportunities to learn and exceed through equivalent public funding.

The primary challenge in achieving this objective can be weighing the balance of local funds compared to state funds. If the state establishes a desired amount of spending on a per-student basis for instance, then it has a financial incentive to ensure that each local district contributes a certain amount to the total, or else the state may be required to fund the desired amount in full, crowding out other state spending priorities. Therefore, a minimum amount of local funding is set by the state, to either receive the additional state funds or to simply comply with state law.

The two main ways that the seven states studied establish minimum funding requirements for education are through either mandatory minimum tax rates, or through establishing a required portion of local education funding to be provided by local property taxes.

Key findings

- Of the states evaluated, Idaho is the only state which does not have a required minimum contribution towards local school districts. California technically also does not have a mandatory minimum however its fixed 1% tax rate acts as a minimum.

- Wyoming is the only state where the state government collects additional local property taxes that are used to distributes across all school districts.

Where Does Local Property Tax Revenue Get Spent?

Unlike income taxes or sales taxes, revenue generated from local property taxes goes primarily to local government functions. These taxing districts, as they are often referred, include school districts, county governments, city governments along with a wide range of local districts, broadly described as special districts.

Key findings

- Arizona is the only state that has any property tax revenue allocated towards state government spending.

- Colorado has the highest percentage of revenue going towards special districts and all states have some form of special taxing districts.

- Wyoming is the only state where the state government collects additional property tax revenue to redistribute to local school districts across the state.

Structure of Property Taxes and Outcomes Across Select Western States

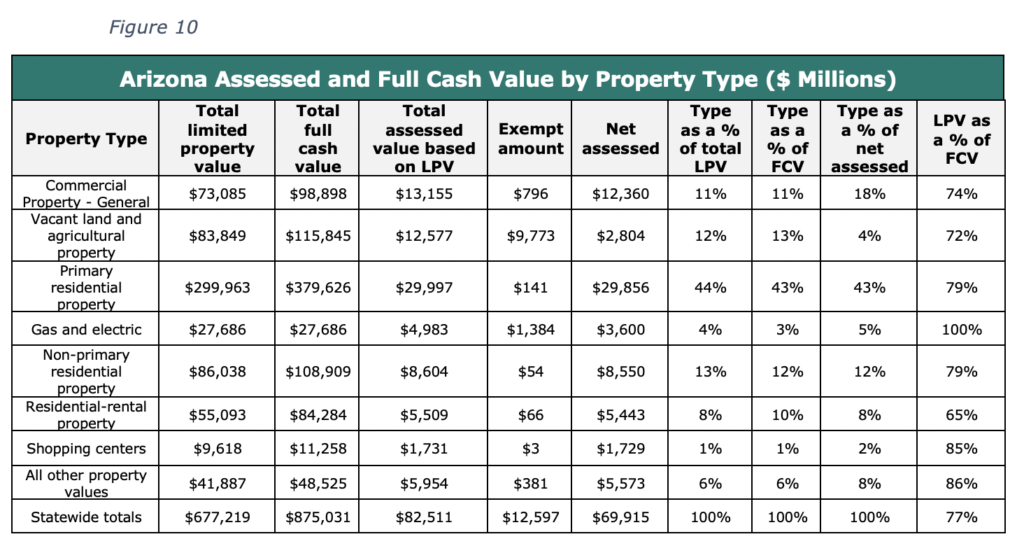

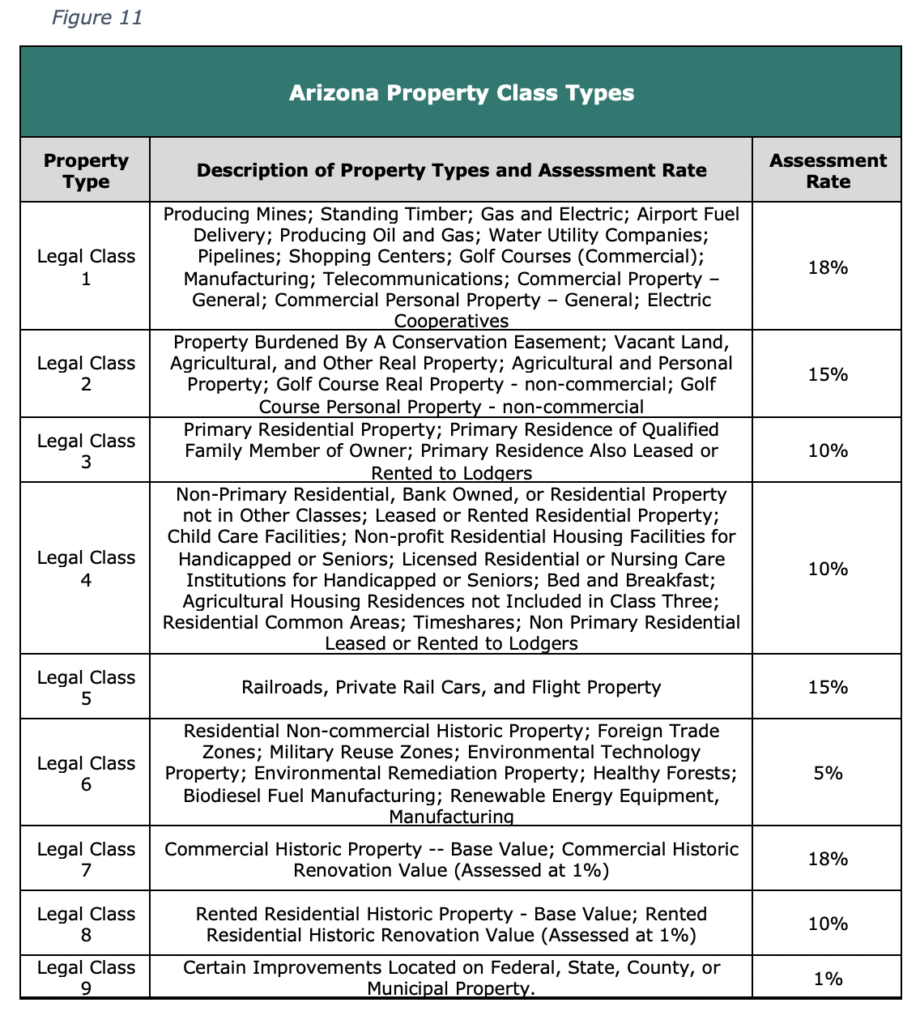

Arizona Summary

Excerpts from description of Arizona property tax system from the Arizona Department of Revenue 2020 “Abstract of the Assessment Rolls.”

“Since 1980, Arizona has operated under two distinct valuation bases for levying the ad valorem property tax. Every property has two values, referred to as the Limited Value and the Full Cash Value. On November 6, 2012, voters approved Proposition 117 which amended the Arizona Constitution. Under the provisions of Proposition 117, beginning in Tax Year 2015, all property taxes, both primary and secondary, are levied against the Limited Value.

Primary taxes are tax dollars generated and used for the maintenance and operation of counties, cities/towns, school districts and community college districts.

Secondary taxes are tax dollars generated and used for debt retirement, voter-approved budget overrides, and the maintenance and operation of special service districts such as sanitary, fire, and road improvement districts.

Limited Property Value (LPV)

The Limited Property Value can equal but cannot exceed the Full Cash Value of a property. Limited Property Valuations are derived on an individual parcel basis by using one of the following methods:

(a) For parcels in existence in the previous year that did not undergo modification through construction, destruction, split, assemblage or change in use, current year Limited Values are established based on the previous year’s Limited Value with no more than a 5 percent increase over the prior year’s Limited Value.

(b) For parcels subject to modification through construction, destruction, or change in use, and for new parcels, including those that were the result of a split or assemblage, Limited Values are established by applying a ratio of Full Cash Value to Limited Property Value of existing properties of the same use or legal classification.

The Limited and Full Cash Values of personal property (except mobile homes) and most centrally valued property are the same.

Full Cash Value (FCV)

Full Cash Value means the value determined as prescribed by statute. If no statutory method is prescribed, Full Cash Value is synonymous with market value. The valuation information displayed in this publication contains both Limited and Full Cash composite valuations for:

(a) Centrally (State) valued property, both real and personal, (utilities, mines, railroads, etc.)

(b) Locally assessed property, both real and personal.”

Links to Arizona Property Tax Data and Description – https://azdor.gov/businesses-arizona/property-tax

2019 Arizona Annual Report – https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/REPORTS_ANNUAL_2019_ASSETS_fy19_annual_report.pdf

Arizona 2020: Abstract of the Assessment Roll – https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/PROPERTY_AbstractAssessmentRoll.pdf

https://sboe.az.gov/faq

Legal class property tax clarifications – https://www.steptoe.com/images/content/1/5/v1/1585/2545.pdf

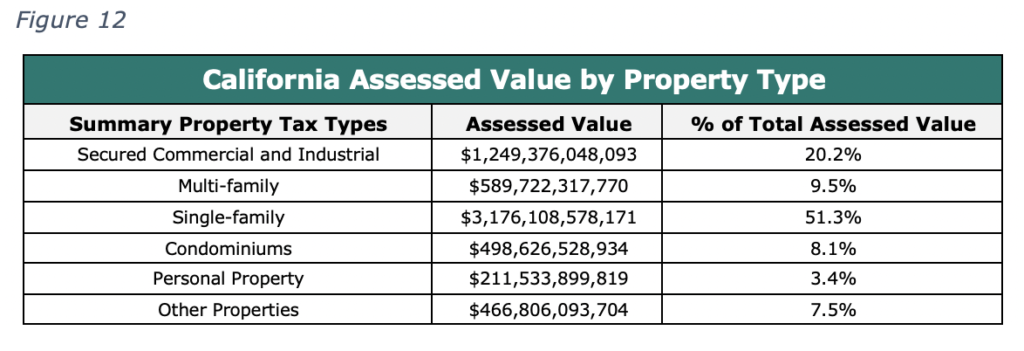

California summary

Excerpts from description of California’s property tax overview from their Board of Equalization office.

“Prior to 1912, the state derived up to 70 percent of its revenue from property taxes. The state no longer relies on property taxes as its primary source of funds—since 1933, the only property tax directly levied, collected, and retained by the state has been the tax on privately owned railroad cars. Currently, the state’s principal revenue sources are personal income taxes, sales and use taxes, bank and corporation taxes, and a series of excise taxes.

Unless the California Constitution or federal law specifies otherwise, all property is taxable. Property is defined as all matters and things—real, personal, and mixed—that a private party can own. Today, it is California’s counties, cities, schools, and special districts that depend on the property tax as a primary source of revenue.

Real Property is defined as: the possession of, claim to, ownership of, or right to the possession of land; all mines, minerals, and quarries in the land, all standing timber whether or not belonging to the owner of the land, and all pertinent rights and privilege; improvements—defined as all buildings, structures, fixtures, and fences erected on or affixed to the land, and all fruit, nut bearing, or ornamental trees and vines, not growing naturally, and not exempt from taxation, except date palms under eight years old. Real property, interests in real property, and taxable possessory interests are taxable in the county where they are located, regardless of where the owner lives. If a parcel of real property spans more than one revenue district, the portion lying within each district is taxable in that district.

Personal Property is defined as: all property except real property. Personal property is either tangible or intangible. Generally, all tangible personal property is taxable except where specific exemptions are provided. Tangible personal property is any property, except land or improvements, that may be seen, weighed, measured, felt, or touched, or which is in any other manner perceptible to the senses.

Secured Roll The county tax collector is responsible for preparing property tax bills. Bills for the regular secured assessment roll (generally real property) are mailed by November 1 and are due in two equal installments. The first installment is due November 1 and becomes delinquent December 10. The second installment is due on February 1 and becomes delinquent April 10. If taxes are not paid by the delinquent date, there is a 10 percent penalty. If a taxpayer receives a notice of impending default, and the taxes remain unpaid on the date the notice says they are due, the property is declared tax-defaulted. Monthly redemption penalties of 1.5 percent are added to the unpaid taxes. The property owner has the right to redeem the property by paying the taxes, penalties, and costs within five years of the date the property becomes tax-defaulted. If the property is not redeemed within five years, the property may be sold at public auction or acquired by a public agency.

Unsecured Roll Property on the unsecured roll is primarily tenant-owned personal property and fixtures (such as office equipment and machinery), boats, aircraft, and possessory interests. Property taxes on the unsecured roll are due in one payment. They are due on January 1 and become delinquent August 31. The property tax rate on unsecured property is based on the previous year’s secured property tax rate. To collect delinquent property taxes on the unsecured roll, the tax collector may seize and sell the property, file suit for taxes owed, seek a summary judgment against the assessee, or file a certificate of lien.”

Links to California Property Tax Data and Description

California Property Tax, An Overview – https://www.boe.ca.gov/proptaxes/pdf/pub29.pdf

California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office 2012 Property Tax Structure Summary – https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2012/tax/property-tax-primer-112912.aspx#:~:text=Under%20California’s%20tax%20system%2C%20the,%2C%20and%20other%20permanent%20structures

California State Board of Equalization 2017-18 Annual Report – https://www.boe.ca.gov/legdiv/2017-2018/pub306.pdf

California Property Tax Exemptions – https://www.boe.ca.gov/proptaxes/exempt.htm

California School Finance Formula – https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/aa/lc/lcffoverview.asp

https://ed100.org/lessons/lcff

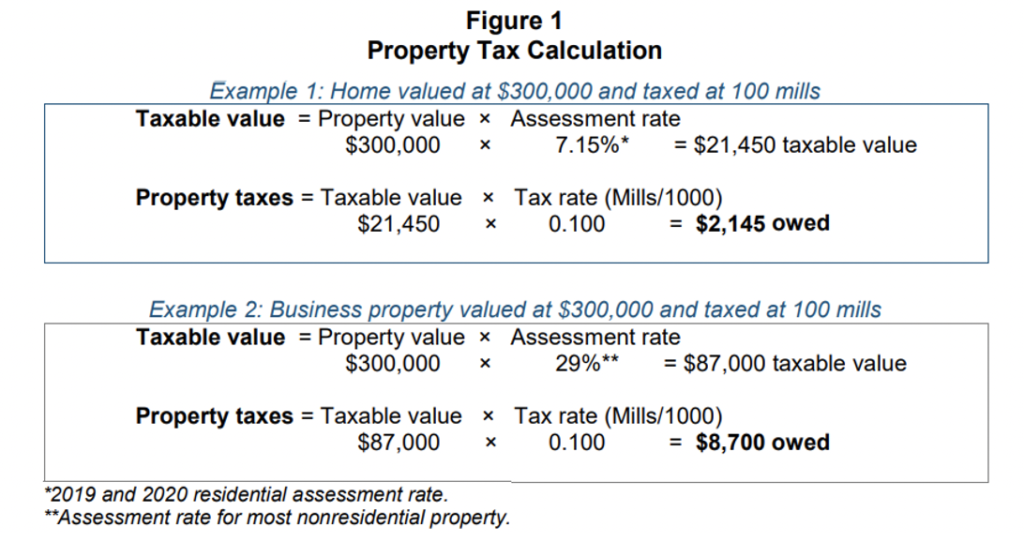

Colorado summary

The following is an excerpt from the description of the Colorado property tax system from the Colorado Legislative Council Staff July 2020 memo “The Gallagher Amendment.”

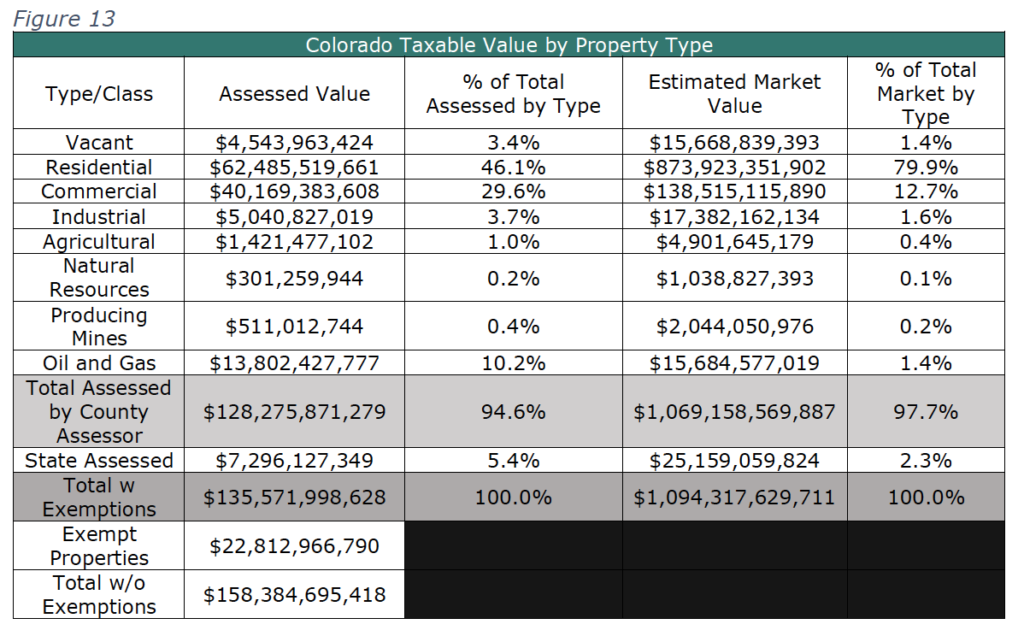

“In Colorado, all property taxes are imposed by and paid to local governments. There is no federal or state property tax. Property taxes are paid on residential and nonresidential property. Nonresidential property includes commercial, industrial, agricultural, business, and oil and gas property, among others. The largest classes of property are residential, commercial, and oil and gas properties. How are property taxes calculated? Property taxes are determined by the actual value of the property, the assessment rate or share of the property value that is taxable, and the number of mills levied by local governments. Figure 1 shows the calculation of property taxes along with examples of property taxes on residential and nonresidential properties valued at $300,000.”

“County assessors determine the actual value of locally assessed property in their county. The division determines the actual value of large utilities and property that exists in multiple counties. The state legislature sets the RAR every two years based on requirements in Gallagher and state law. Finally, mills are a local tax rate determined by local governments, including school districts, cities, counties, and special districts. The taxable value or assessed value of a property is equal to the actual value of the property multiplied by the assessment rate. The property tax base of a given local government is the sum of all the taxable values of individual properties within its jurisdiction, an area commonly known as a taxing district.

The actual value of most real property is updated on a two-year reassessment cycle to reflect current property values. For residential property, county assessors use recent sales of similar properties to reassess every property in the county. For most nonresidential property, county assessors use recent sales, recent income, or recent cost estimates to value the property. For the 2021 reassessment cycle, county assessors will value each property as of July 1, 2020 and the property will be taxed on that value beginning January 1, 2021. The actual value will remain constant for 2021 and 2022 and be reassessed in 2023. If assessment rates do not change, the taxable value of a property will change proportionally to the change in the property’s actual value. The nonresidential assessment rate for most nonresidential property is fixed at 29 percent in the Constitution, and the residential assessment rate is adjusted every two years, following the reassessment cycle based on the requirements of Gallagher.”

Links to Colorado Property Tax Data and Description

Colorado Special District – https://cdola.colorado.gov/special-districts

Colorado Counties, Inc. Resources – https://ccionline.org/info-center-library/research-miscellaneous-publications/

Colorado School Finance Formula – https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdefinance/generalinfo

DOLA Division of Property Taxation 2019 Annual Report– https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QyS0LzOrYeygHMH9dDfR2UYw0J5-apJ8/view

Idaho Summary

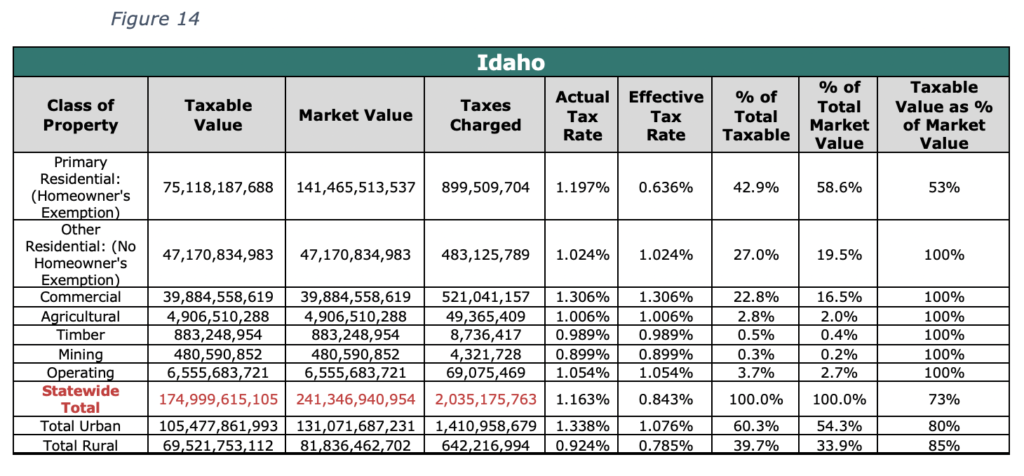

Excerpts are from Idaho’s, “Understanding Property Tax” review.

“To understand Idaho’s tax assessments and rates, the structure needs to be understood. Counties levy and collect property tax to provide local services and support for independent local taxing districts, such as cities and schools. The State of Idaho doesn’t receive any property tax. Property tax applies to all nonexempt property including: Homes (including manufactured housing); Farmland; Commercial properties; Industrial properties; Business personal property (if owned by a single taxpayer and with an aggregate value greater than $100,000 per county).

The role of the Tax Commission is to oversee the property tax system and ensure compliance with state laws. The Tax Commission also determines the assessed value of operating property such as electric utility companies, railroads and railcar companies. The Tax Commission doesn’t collect property tax. Each year the county assessor’s office must estimate how much a typical buyer would pay for your property as of January 1. It is assessed at 100% of market value less any exceptions. One can check with their county assessor to determine what constitutes as an exemption. Generally speaking, assessors use sales prices from properties in the county to develop guidelines. They also consider features that could influence what a buyer would pay for the property. These features include size, location, quality of construction, age and condition.

Idaho law doesn’t limit increases or decreases to property value from year to year

Your property value can change periodically for reasons: changes to the market value of all properties in your neighborhood; your county assessor’s office discovers more accurate information.

Several factors can affect your property value. These factors include the addition of new structures or making other improvements that add value. Market conditions also can affect your property value, even if you don’t make any physical changes to it.

There’s no legal limit to how much any property’s tax bill can increase or decrease. But each taxing district can raise the property tax portion of its budget by no more than 3% unless one or both of these apply: voters approve an increase to property tax revenue (e.g., bonds, overrides); your taxing districts apply new construction or new annexations.”

Links to Idaho Property Tax Data and Description

Idaho State Tax Commission

Understanding Property Tax – https://tax.idaho.gov/i-1129.cfm

Market Value Reports – https://tax.idaho.gov/search-reports.cfm?ch=EPB00132

2019 Annual Report – https://tax.idaho.gov/reports/EPB00033_12-16-2019.pdf

Property Tax Reductions – https://tax.idaho.gov/i-1052.cfm

Utah summary

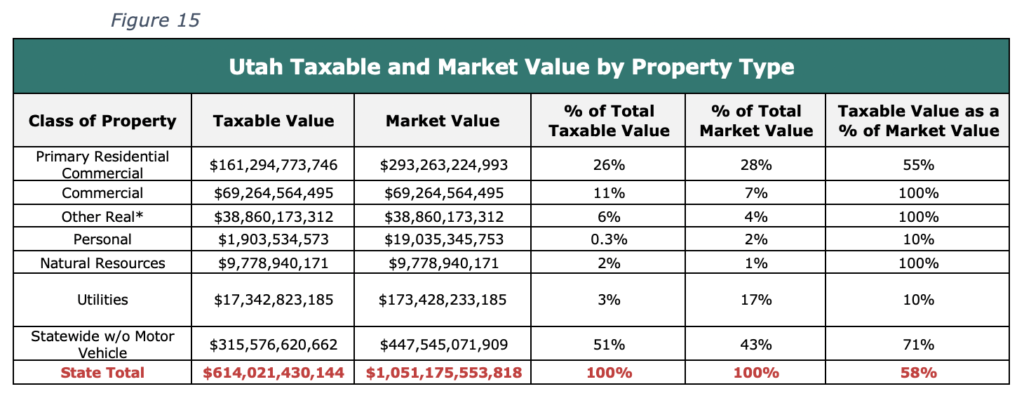

Excerpts are from the “Utah Property Tax Annual Statistical Report.”

“Property Value with the exception of state-assessed properties, county assessors value all taxable real property and personal property which are collectively referred to as locally assessed property. The Property Tax Division of the State Tax Commission values utilities, mines and railroads, which are collectively referred to as centrally assessed property.

All taxable property in Utah is valued at 100 percent of its fair market value, based upon its location and status as of January 1st of each year. Fair market value less any exemptions equals taxable value. Taxable value is the value against which the tax rate is applied to compute taxes charged.

Fair market value means the amount at which property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or sell and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.

See Utah Code Annotated Section 59-2-103. 3 See Utah Code Annotated Section 59-2-501 through 516. 4 Age based fees are not based on market value. Numbers in this report are converted to an estimated market value. This value per Administrative Rule R884-24P-60(M) is calculated by dividing age-based revenues by 0.015.

Currently, primary residential properties receive a 45% exemption. Primary residential property is any dwelling used as a person’s primary residence, including condominiums, apartments and rental property, and includes up to one acre of land. The taxable value of all other properties, except some agricultural land, is assessed at 100% of fair market value. Utah motor vehicles are charged a fee-in-lieu of property taxes which is identified throughout this report as “fee-in-lieu.” This report addresses taxable value.

The relationship of taxable value to fair market value is illustrated in the table below.”

Links to Utah Property Tax Data and Description

Utah Property Tax Annual Statistical Reports – https://propertytax.utah.gov/annual-reports/2019annual.pdf

How Property Taxes Work in Utah – https://www.webercountyutah.gov/Assessor/how_tax.php

Utah Association of Special Districts – https://www.uasd.org/about-us

Utah Certified Tax Rates – https://propertytax.utah.gov/rates/

Utah Basic Tax Levy for Education – https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title59/Chapter2/59-2-S902.html

Utah Property Tax Descriptions from Dept Board of Education – https://www.schools.utah.gov/financialoperations/propertytax?mid=2198&tid=0

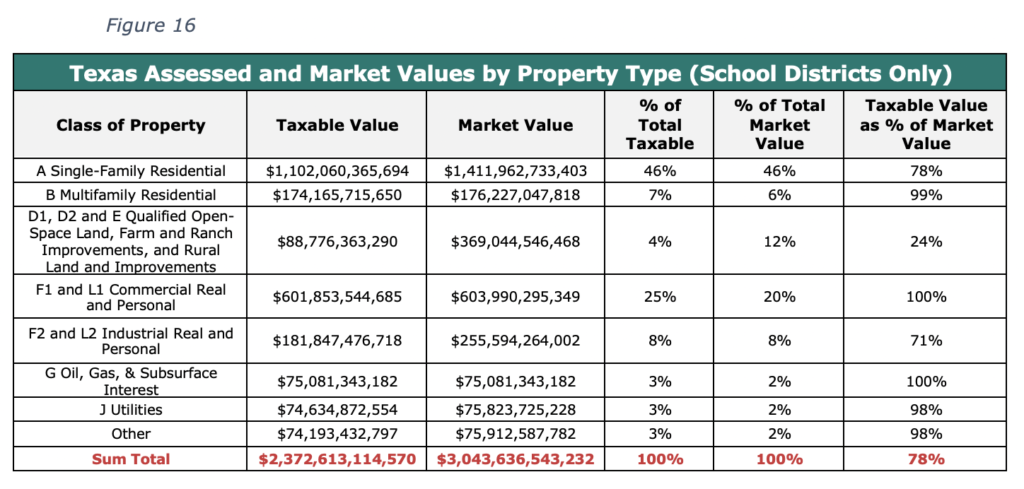

Texas Summary

Excerpts are from the “Texas Property Tax Basics,” report.

“The state of Texas has no property tax. Local governments set tax rates and collect property taxes that are used to provide local services including schools, streets, roads, police, fire protection, and many other services.

Texas law requires property values used in determining taxes to be equal and uniform and establishes the process to be followed by local officials in determining property values, setting tax rates, and collecting taxes. The Texas Property Taxpayer Bill of Rights requires all property to be taxed equally and uniformly. No single property or type of property should be taxed more than its fair market value.

There are several types of local governments may tax property Texas counties and local school districts tax all nonexempt property within their jurisdiction Cities and special purpose districts such as hospitals, junior colleges or water districts, may also collect certain property taxes.

The Comptroller’s office helps ensure that taxpayers have the information needed to preserve their rights and pursue appropriate remedies. In keeping with this commitment, the Comptroller’s Property Tax Assistance Division (PTAD) created the summary of property tax rights.

As a taxpayer, it is important for a property owner to understand how government spending affects the size of a tax bill. Changes in property values may affect a tax bill, but do not necessarily increase or decrease the total amount of taxes paid to a taxing unit; that is determined by the taxing unit’s budget. Total taxes collected increase only when government spending increases, but Texas law gives taxpayers a voice in decisions affecting property tax rates.”

Links to Texas Property Tax Data and Description

Texas Property Tax Basics – https://comptroller.texas.gov/taxes/property-tax/docs/96-1425.pdf

Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

Biennial Property Tax Report – https://comptroller.texas.gov/search/?site=ctg_collection&q=property+tax+biennial

Texas Comptroller: Property Tax Assistance – https://comptroller.texas.gov/taxes/property-tax/

School funding requirement – https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/fiscal-notes/2019/jan/funding.php

Wyoming Summary

Excerpts are from the “Wyoming Tax Facts: Property Tax,” report.

“If you own real estate in Wyoming, you pay property taxes on that property. Property taxes are applied to land and anything attached to the land, such as a home or other building, fence, or shed. Property taxes are an important source of funding for our local governments; however, because many homeowners have their property tax bill rolled into their monthly mortgage payment, it’s easy to forget or ignore the annual bill that we pay. Even though we may not see the separate bill every month, it is important for property owners in Wyoming to understand the property taxes we pay and what our property taxes fund.

Property tax is an ‘ad valorem’ tax, which means it is based on the value of the thing being taxed, so the value of your property determines how much tax you pay, the greater the property value, the higher the tax.

A tax district is a geographical area where a certain taxing authority has the right to levy, or collect, a tax. Taxing authorities include school districts, counties or cities, water districts, fire districts, and other specially formed districts that have been designated by state statute. These taxing authorities have a geographical boundary, or district, where they can levy a tax. Sometimes a tax district encompasses an entire city or county, but usually it divides a county into smaller areas for taxation purposes. For example, most counties in Wyoming have multiple school districts. Depending on where you live in a county, you fall within one specific school district’s boundary. This determines which school you or your children attend, and it also determines which school district receives funds from the property taxes you pay. Some tax districts even span multiple counties; for example, a hospital district might levy taxes on individuals residing within its boundary, which might include multiple counties.

The simple definition of a “mill” is one one-thousandth (1/1,000, or 0.001). When we consider a “mill” in relation to property taxes, a mill is how much money someone pays for every thousand dollars of taxable property they own. Each taxing authority or tax district has a legal right to collect a certain number of mills on the property in its district and is subject to certain minimum and maximum limits of mills.

The “mill levy” is the total number of mills applied to the assessed value of property. Depending on where the property is located, it may fall into several distinct tax districts: a school district, community college district, fire district, weed and pest district, and so on. These tax districts, typically governed by a board of directors, determine their budgetary needs each year. Then they determine the mills necessary to provide the funds to meet their budget, and the county commissioners in that county approve the mill levies each year. The mill levy is the combined total of all of the mills charged by all the tax districts that have taxing authority in the area where your property is located.”

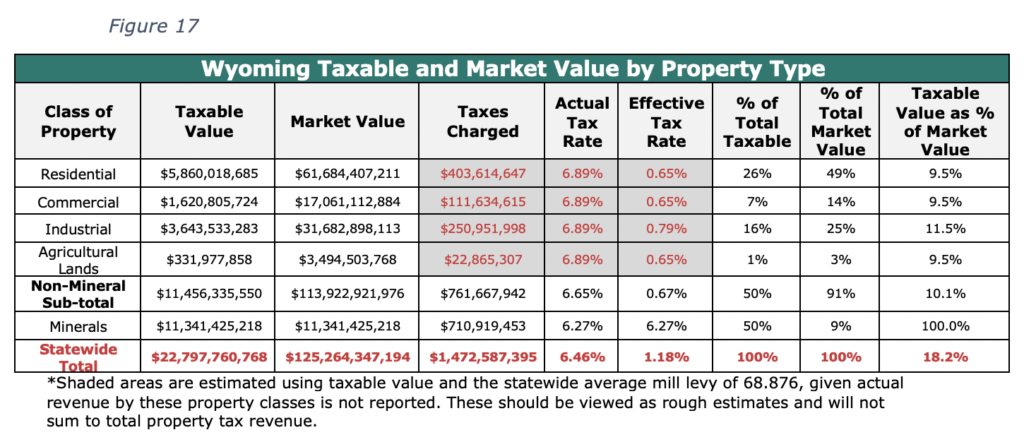

*Shaded areas are estimated using taxable value and the statewide average mill levy of 68.876, given actual revenue by these property classes is not reported. These should be viewed as rough estimates and will not sum to total property tax revenue.

Links to Wyoming Property Tax Data and Description

Wyoming Tax Facts: Property Tax – http://wyoextension.org/publications/html/MP130-3/

State Board of Equalization – http://taxappeals.state.wy.us

Wyoming Property Tax Division – http://wyo-prop-div.wyo.gov/tax-districts

Wyoming Property Tax Relief – http://wyo-prop-div.wyo.gov/tax-relief

[i] https://gazette.com/colorado_politics/fitch-maintains-colorado-s-credit-ratings-in-wake-of-ballot-initiatives/article_0a1f9f4c-f6b8-51cd-a97f-7352116e4a0e.html

[ii] https://www.reporterherald.com/2020/11/06/moodys-praises-gallagher-amendment-repeal-as-a-boon-for-colorados-creditworthiness/

[iii] https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/the-inherent-tradeoffs-in-amendment-b/

[iv] Active Colorado Local Governments (4,180 local governments) | Colorado Department of Local Affairs