About the Authors

Chris Brown is the Director of Policy and Research with Common Sense Institute where he leads the research efforts of CSI to provide insightful, accurate and actionable information on the implications of public policy issues throughout the state of Colorado.

Erik Gamm is the Research Analyst with Common Sense Institute where he supports the research efforts of CSI. Erik recently graduated from the University of Michigan in 2020 with a Bachelor of Arts in Economics.

About Common Sense Institute

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

Key Findings

- If passed, Amendment B would repeal the primary law governing how property taxation works in Colorado. However, whether Amendment B passes or fails, many issues surrounding the future of the state’s system of property taxation will remain, and still require a long-term solution.

- The history of property tax revenue, and the relative tax burden since the passage of the Gallagher Amendment has produced some clear trends.

-

- Given residential property value has outpaced commercial, the residential assessment rate has fallen from 21% in 1983, to 7.15% in 2019.

- Residential property paid 46% of total local property tax revenue in 2019, despite consisting of 79% of all local property value.

-

- Businesses in some Colorado cities pay much higher effective property tax rates than businesses in large cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

-

- For example: Denver, Colorado Springs, and the small city of Walsenburg in Southern Colorado have effective property tax rates of between 2.039% and 2.295%, compared to 1.317% in New York, 1.180% in San Francisco and 1.175% in Los Angeles, according to data from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

-

- If passed, Amendment B would have the effect of freezing the residential assessment rate at 7.15% and most non-residential assessment rates at 29%.

-

- Freezing the residential assessment rate would halt the anticipated reduction to 5.88%, which is estimated to reduce local property tax revenue by nearly $700 million annually.

- Residential homeowners will likely pay higher taxes in the future as their property tax burden will grow in-line with the value of their home.

-

- The legislature would be able to lower residential or non-residential assessment rates in future years, but still cannot raise rates, unless referred to voters.

- While Colorado households will continue to pay some of the lowest property taxes in the country, if Amendment B fails, the current trends brought about from the existing property tax formula will continue.

-

- The anticipated reduction in the residential assessment rate to 5.88%, and associated reduction in local tax revenue would likely prompt a series of further government and fiscal responses.

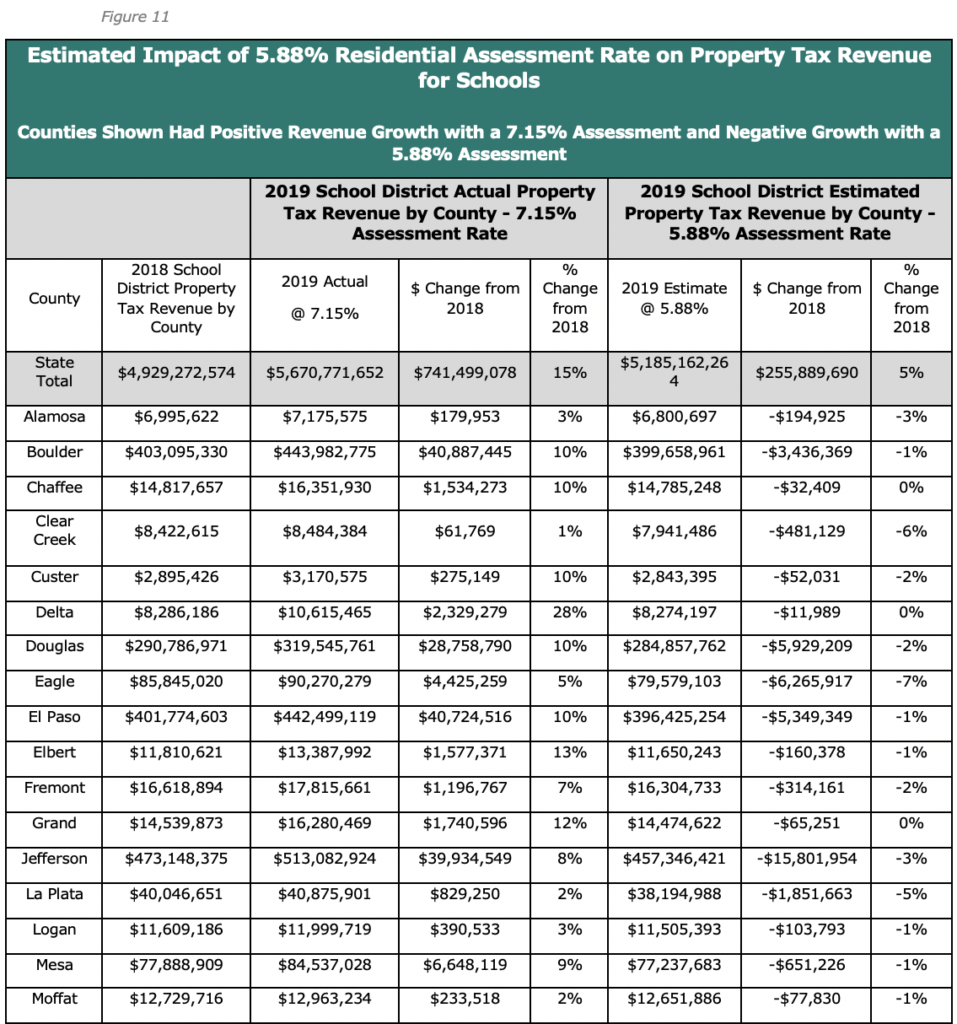

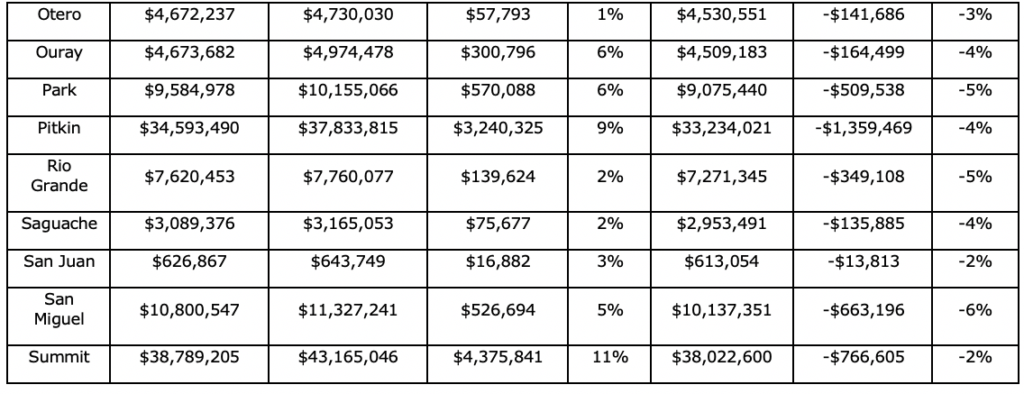

- Lower local property tax revenue to K-12 school districts will increase the pressure on the State General Fund budget to backfill funding for K-12 education. DOLA modeling of 2019 property data indicates that property tax revenue across all school districts in 26 counties, including, Mesa, Pitkin, Park and Alamosa, would have experienced a reduction in revenue from 2018 to 2019, if the anticipated lower assessment rate of 5.88% were enacted.

-

Overview of Amendment B

This fall, Colorado voters will be asked to approve or reject a proposed reform of the state’s property tax system through a repeal of the Gallagher Amendment of 1982. The proposed repeal was referred to the ballot during the 2020 legislative session by supermajorities of the Colorado State House and Senate.

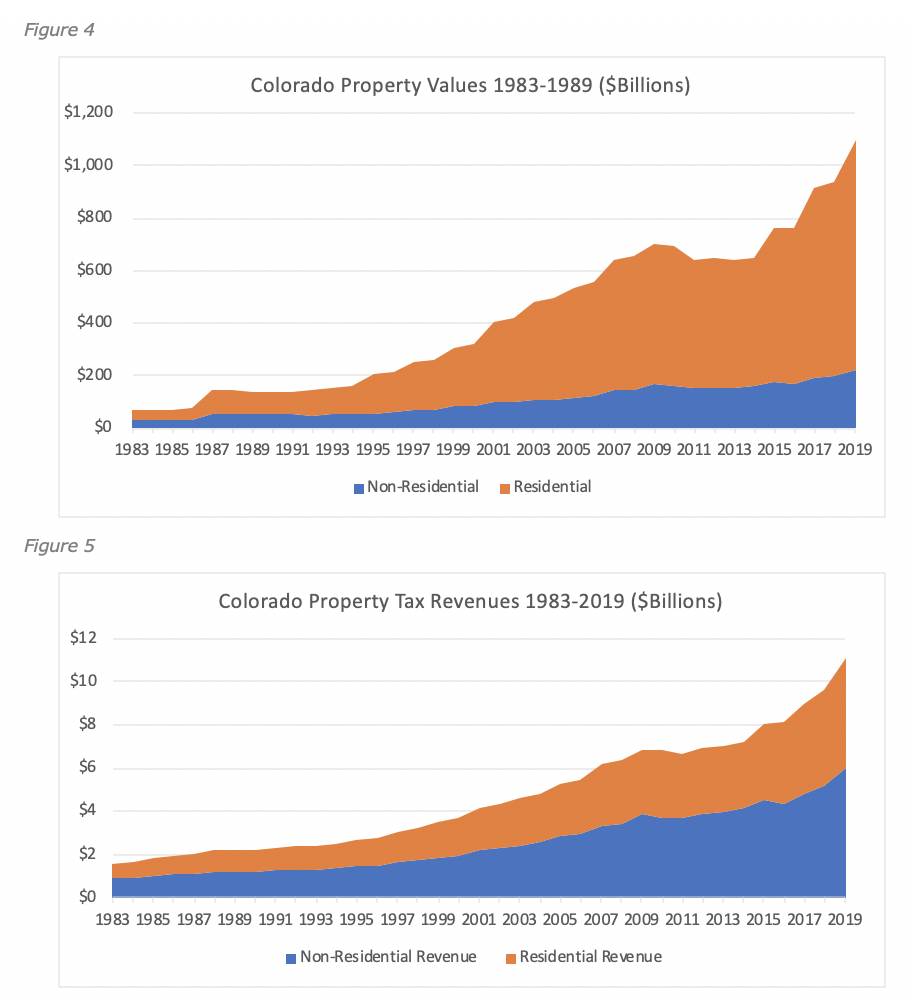

The Gallagher Amendment governs the collection of property taxes, which are a major source of revenue for services provided by local governments in Colorado. In 2019, for example, property taxes raised $11.08 billion for K-12 education, municipal and county government, fire and rescue services, water and sanitation infrastructure, parks and recreation departments, hospitals, libraries and other local services.[i]

Amendment B would:

- Repeal the Gallagher Amendment’s fixed statewide formula that requires approximately 45% of total taxable property to come from residential property and 55% to come from non-residential property.

- Keep property tax assessment rates in state law at their current levels (i.e. 7.15% for residential property and 29% for most types of non-residential property).

- End the practice of automatic decreases in the residential property tax assessment rate to maintain the Gallagher formula’s 45/55 split between residential and non-residential tax revenues.

- Subject any proposed increases in tax assessment rates to voter approval as required under the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights in the Colorado Constitution.

History of the Colorado Constitutional Amendment Known as the “Gallagher Amendment”

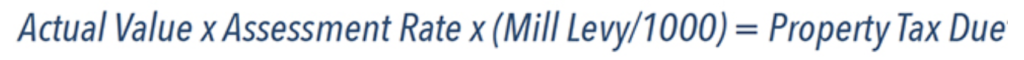

Colorado property taxes are determined under a process that is partially controlled by the state and partially controlled by local taxing authorities, such as cities, counties and school districts. The process can be described in the following manner:

The actual value of a property is determined every two years by county-level officials, with the exception of public utilities and railroads, which are assessed by state officials. Local taxing authorities, with the approval of voters, determine the mill levies that apply to properties within their respective jurisdictions. But the assessment rate – which determines how much of a property’s value is subject to local mill levies – is set by the state and controlled by a constitutional formula that was created by the Gallagher Amendment.

The actual value of a property is determined every two years by county-level officials, with the exception of public utilities and railroads, which are assessed by state officials. Local taxing authorities, with the approval of voters, determine the mill levies that apply to properties within their respective jurisdictions. But the assessment rate – which determines how much of a property’s value is subject to local mill levies – is set by the state and controlled by a constitutional formula that was created by the Gallagher Amendment.

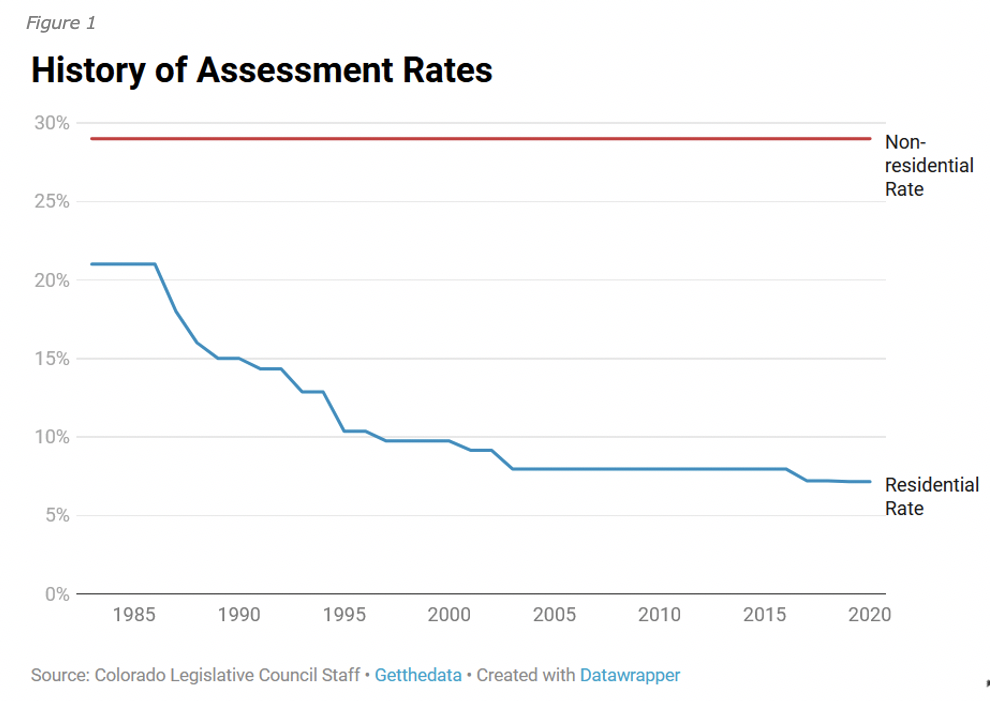

The Gallagher Amendment of 1982 was added to the Colorado Constitution by voters to stabilize the residential and non-residential share of the state’s property tax base, after significant escalations in residential property taxes in the 1970s. In the years immediately following the passage of the Gallagher Amendment, residential property tax assessment rates did stabilize, i.e. from 1983 to 1986, the residential property tax assessment rate remained at 21%. However, since the late 1980s, the Gallagher formula – when combined with prevailing real estate trends – has dramatically reduced residential property tax assessment rates, with further reductions expected in the coming years as shown in Figure 1.

When Gallagher came into force, roughly 45% of property subject to local mill levies in Colorado was residential, and 55% was non-residential. The Gallagher formula effectively requires the 45/55 ratio that existed in the early 1980s to remain relatively constant. Under Gallagher, to maintain the 45/55 ratio, the state legislature must reset the residential assessment rate every two years. However, Gallagher does not allow any change in the assessment rate – or the percentage of a property’s value that is subject to local mill levies – for commercial, agricultural, industrial and other non-residential property classes.

When Gallagher came into force, roughly 45% of property subject to local mill levies in Colorado was residential, and 55% was non-residential. The Gallagher formula effectively requires the 45/55 ratio that existed in the early 1980s to remain relatively constant. Under Gallagher, to maintain the 45/55 ratio, the state legislature must reset the residential assessment rate every two years. However, Gallagher does not allow any change in the assessment rate – or the percentage of a property’s value that is subject to local mill levies – for commercial, agricultural, industrial and other non-residential property classes.

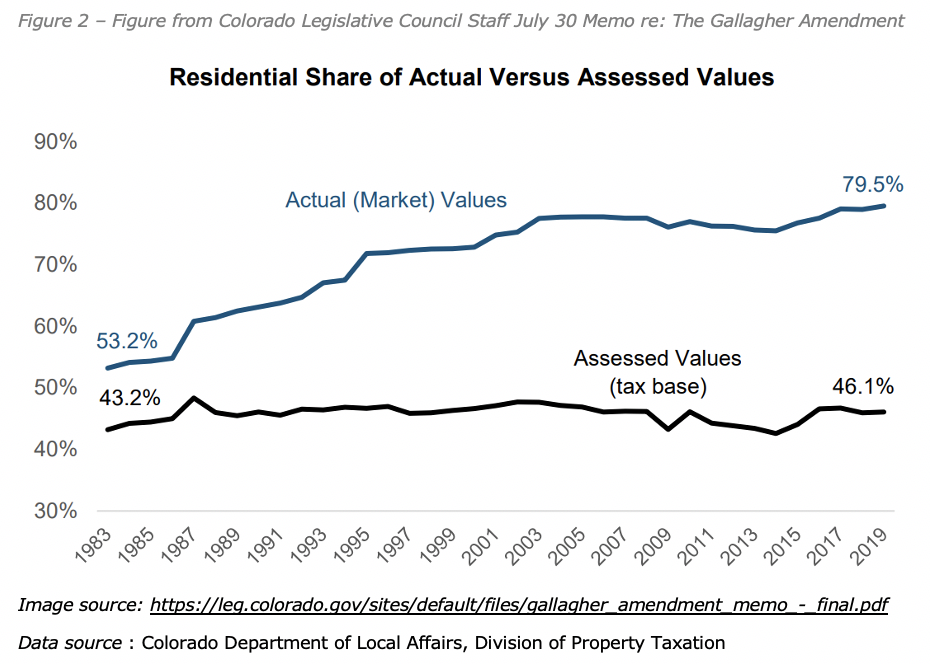

Over the past four decades, residential property values have increased at a higher rate than non-residential property values in Colorado. In 1983, the market value of residential properties was 53.2% of all property value. In 2019, the residential share grew to 79.5%.[ii] The residential market trend, together with the application of the Gallagher Amendment, has resulted in repeated reductions in the assessment rate for residential property in order to maintain the 45/55 ratio – from 21% in 1983 to 7.15% in 2020. This represents a 65.95% reduction in the residential property tax assessment rate.

However, the Gallagher formula locked in place the assessment rate for all other property classes. For commercial and agricultural property, this assessment rate is 29%, but varies for oil and gas and producing mines as shown in Figure 2.

However, the Gallagher formula locked in place the assessment rate for all other property classes. For commercial and agricultural property, this assessment rate is 29%, but varies for oil and gas and producing mines as shown in Figure 2.

Over time, fixed non-residential rates and a declining residential rate, has increased the ratio of commercial and agricultural property tax rates to residential property tax rates from 1.38:1 in the early 1980s to 4.06:1 today.

Over time, fixed non-residential rates and a declining residential rate, has increased the ratio of commercial and agricultural property tax rates to residential property tax rates from 1.38:1 in the early 1980s to 4.06:1 today.

At the same time, however, the non-residential sector – which includes retail, restaurants, hotels, office buildings and farmland – now represents a much smaller share of the state’s property values. In 1983, non-residential property represented 46.8% of actual property values. In 2020, the non-residential share of actual property values has contracted by more than half to 20.46%. However, under the Gallagher formula, non-residential property classes are still required to pay roughly 55% of all property tax revenues.

By contrast, in 1983 the residential sector represented 53.2% of actual property values. In 2020, the residential share of actual property values stood at 79.54%, driven by both a growing population size and appreciating value of homes. However, under the Gallagher formula, the residential sector pays a significantly smaller share – 45% – of the state’s property tax revenues.

The net effect of the Gallagher formula, therefore, has been to move the state’s property tax base away from the fastest growing sector (i.e. residential) towards the slowest growing sector (i.e. non-residential).

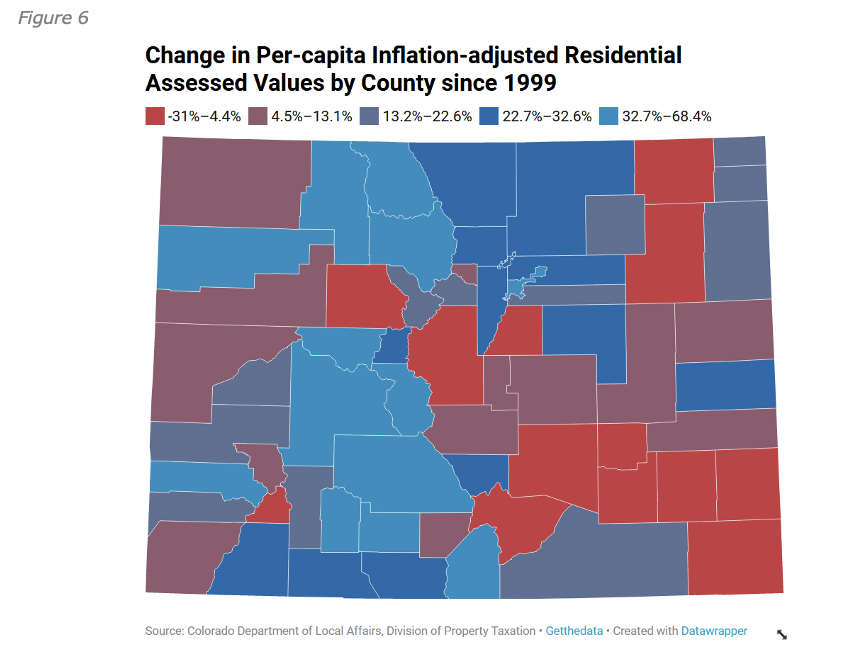

In the early 2000s, the Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) identified another significant trend: Major regional disparities in the impacts of the statewide Gallagher formula. For example, during the 2001 budget year, DOLA found that statewide property tax revenues increased 5.3% and yet more than 200 local taxing authorities faced significant revenue shortfalls. “This is over 20% of all property taxing jurisdictions, many of which are small, rural entities facing severe budget cuts, although their decline in revenue represented less than 1/10 of one percent loss in the overall property tax system,” the DOLA report concluded.[iii]

In the early 2000s, the Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) identified another significant trend: Major regional disparities in the impacts of the statewide Gallagher formula. For example, during the 2001 budget year, DOLA found that statewide property tax revenues increased 5.3% and yet more than 200 local taxing authorities faced significant revenue shortfalls. “This is over 20% of all property taxing jurisdictions, many of which are small, rural entities facing severe budget cuts, although their decline in revenue represented less than 1/10 of one percent loss in the overall property tax system,” the DOLA report concluded.[iii]

In 2018, a bipartisan study committee was convened to examine the Gallagher Amendment and its effect on homeowners, business owners, local governments and the state budget. The study committee also highlighted significant “regional disparities” that have resulted from the statewide Gallagher formula and significant appreciation in home values along Colorado’s I-25 corridor:

The growth and home price appreciation in the housing markets along the Front Range largely drove the required statewide reduction in the residential assessment rate. Several local governments outside of the Front Range shared how assessed values declined in their districts even though home prices increased, resulting in local government budgetary pressures that required counties and special districts to reduce the services provided to cut costs.[iv]

More recently, in July 2020, a staff report from the Legislative Council of the Colorado General Assembly echoed these findings:

The impact of Gallagher has varied across different regions of the state. In some rural areas where property values have not increased as significantly, Gallagher has resulted in substantial reductions in the tax base.[v]

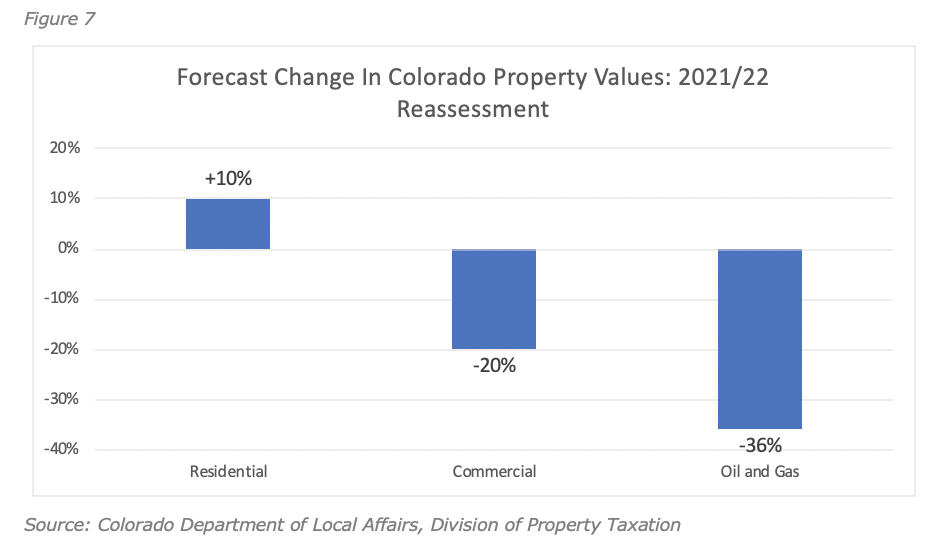

In addition to these long-term trends, recent research into the Gallagher Amendment has focused on how the application of the statewide formula may be affected by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. In short, state officials and analysts have concluded that the most likely outcome is significant reduction property tax revenues due to the different forces impacting residential and non-residential property classes.

In addition to these long-term trends, recent research into the Gallagher Amendment has focused on how the application of the statewide formula may be affected by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. In short, state officials and analysts have concluded that the most likely outcome is significant reduction property tax revenues due to the different forces impacting residential and non-residential property classes.

According to DOLA’s Division of Property Taxation, the three largest classes of property in Colorado in terms of value are residential, commercial and oil and natural gas.[vi] In response to the COVID-19 recession, commercial and oil and gas property valuations are falling – but residential valuations continue to grow.

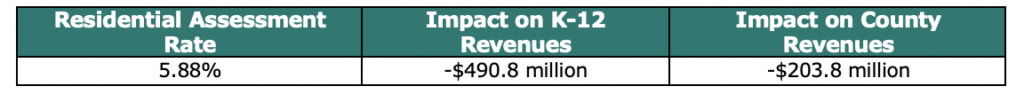

According to an analysis prepared for lawmakers, the Gallagher formula – which resets property tax assessment rates every two years – is expected to reduce the residential property tax assessment rate from 7.15% to 5.88% in 2021. According to the same analysis, this anticipated application of the Gallagher formula, and reduction in the residential assessment rate, would reduce school district and county property tax revenue by nearly $700 million, or an 8.5% reduction relative to previously anticipated level. Of the total reduction, an estimated $491 million would come from K-12 funding and the additional $204 million would come from county-level services.[vii]

According to an analysis prepared for lawmakers, the Gallagher formula – which resets property tax assessment rates every two years – is expected to reduce the residential property tax assessment rate from 7.15% to 5.88% in 2021. According to the same analysis, this anticipated application of the Gallagher formula, and reduction in the residential assessment rate, would reduce school district and county property tax revenue by nearly $700 million, or an 8.5% reduction relative to previously anticipated level. Of the total reduction, an estimated $491 million would come from K-12 funding and the additional $204 million would come from county-level services.[vii]

However, if Amendment B is approved by voters, the residential property tax assessment rate would remain unchanged at 7.15%. Meanwhile, the non-residential property tax assessment rate would also remain where it has stood for almost four decades at 29%.

However, if Amendment B is approved by voters, the residential property tax assessment rate would remain unchanged at 7.15%. Meanwhile, the non-residential property tax assessment rate would also remain where it has stood for almost four decades at 29%.

Critics of the Gallagher Amendment argue that almost four decades of automatic cuts in the residential property tax assessment rate have created major funding shortfalls for essential services – especially in rural areas of the state – and are no longer sustainable. In 2018, for instance, State Representative Daneya Esgar, Pueblo, said “what I think people need to understand is this well-intentioned Gallagher Amendment is actually putting a chokehold on counties across Colorado.”[viii]

Gallagher critics also argue that shifting the state’s property tax burden increasingly on businesses, farms, ranches and other non-residential property harms the competitiveness of the Colorado economy, and if the Gallagher formula remains in effect, this trend will significantly worsen. For example, in 2018, Logan County Commissioner Byron Pelton said the Gallagher formula “really puts a burden on the economic drivers in our community … You can’t be pro-economic development and also be pro-Gallagher.”[ix]

However, some supporters of the Gallagher formula argue that the continued tax shift to non-residential property owners is justified. For example, former state House Speaker Dickie Lee Hullinghorst has said removing the Gallagher formula from the Colorado Constitution may “end up hurting the average property owner quite a bit, and business taxes are going to go down.”[x]

Supporters of the Gallagher formula point out that homeowners will pay more in property taxes under the current 7.15% residential assessment rate than they would under a residential assessment rate of 5.88% – although this assumes local mill levies would not be subsequently raised in order to maintain municipal, county and school budgets. Some defenders of the Gallagher formula have further argued that keeping the existing residential assessment rate, rather than allowing another automatic reduction, amounts to a tax increase.

What Are the Likely Impacts If Amendment B Passes?

If Amendment B passes, the formula for determining annual property tax assessment rates for different classes of property would no longer exist. Instead of the use of the Gallagher formula contained with the constitutional Amendment, the current assessment rates across different property types would be frozen. This would have both short-term, and long-term impacts.

A Frozen Residential Assessment Rate Would Stop a Revenue and Tax Cut Next Year, And Lead to Increased Revenue and Effective Taxes in Long-term

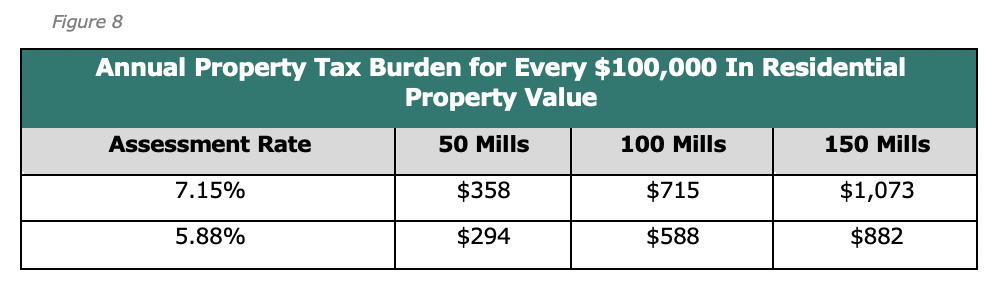

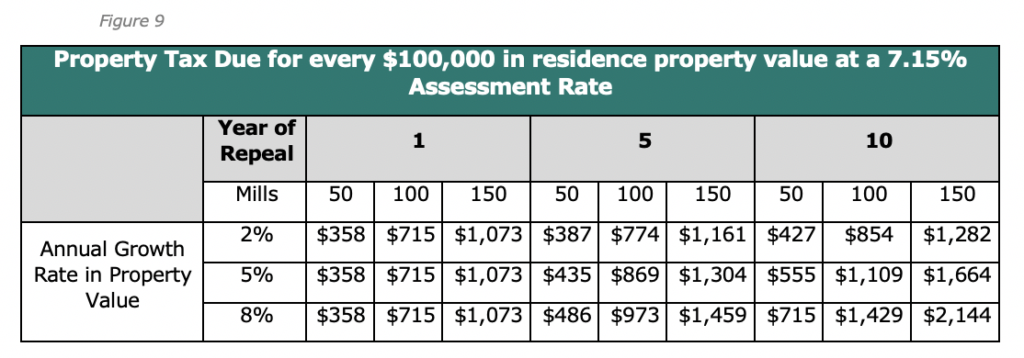

Given the estimate for next year’s residential property assessment rate was projected to drop to 5.88%, fixing the current rate effectively means that against the current baseline, residential property owners will pay more next year than they would under current law. For every $100,000 in residential property value, maintaining the residential assessment rate at 7.15% means that in a tax jurisdiction that levies 100 mills, the homeowner will pay $127 more in property taxes than if the assessment rate were at 5.88%.

In many ways, a fixed residential assessment rate, puts the state’s residential property tax structure exactly where it was prior to the passage of the Gallagher Amendment in the early 80s. While the rate is significantly lower than it was in the 80s, falling from 21% to 7.15%, the annual amount that residential property owners pay in property taxes, will grow according to the growth rate in the value of their property, or home. And given the residential property values have far outpaced inflation, over-time, the rise in property taxes could likely grow as a share of income.

In many ways, a fixed residential assessment rate, puts the state’s residential property tax structure exactly where it was prior to the passage of the Gallagher Amendment in the early 80s. While the rate is significantly lower than it was in the 80s, falling from 21% to 7.15%, the annual amount that residential property owners pay in property taxes, will grow according to the growth rate in the value of their property, or home. And given the residential property values have far outpaced inflation, over-time, the rise in property taxes could likely grow as a share of income.

Figure 8 below shows the current amount that individuals pay in property taxes, and how that would change in the future dependent upon the growth rate in the value of their property.

Non-Residential Assessment Rate Freezes at Higher Rate of 29%

Non-Residential Assessment Rate Freezes at Higher Rate of 29%

Over the years, as the share of residential property subject to taxation falls, many local communities have chosen to raise property tax rates through mill levy increases. For businesses, higher mill levies are not offset by a reduced assessment rate, which the Gallagher formula has held constant at 29% since the early 1980s. Business groups in Colorado argue this trend is harmful to the competitiveness of the state economy.

In 2018, the Colorado chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business argued these “escalating property taxes” are “crushing some small businesses.” That is because, according to NFIB, “if business revenues can’t keep up with property tax liability, the increased value becomes a ball and chain.”[xi]

Data compiled by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy shows how this trend may impact the competitiveness of Colorado’s business climate. Each year, the Lincoln Institute compares the effective property tax rates of large and small cities across the country.[xii] In the institute’s 2020 analysis, three Colorado cities – Denver, Colorado Springs and Walsenburg – were included and all three have significantly higher effective property tax rates than New York, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and Seattle.

The magnitude of the difference between business property taxes in Colorado and some of the nation’s largest population centers may be surprising to many – especially in the case of Walsenburg, as small city just 50 miles south of Pueblo along I-25. But the underlying trend of rising business property taxes in Colorado is both longstanding and widely recognized. For example, a 2001 report from DOLA observed the following:

As the residential assessment rate is annually decreased … to maintain the 45/55% ratio in assessed value and property taxes paid, the relative burden of property tax is increasingly borne by properties in all other classes collectively. Therefore, although the actual value of all other classes is relatively less each year, they still have to pay the same 55% proportionate share of all property taxes paid.

Therefore, the operation of Gallagher has not only limited tax increases to residential property owners, as was its intent, but has also resulted in an increased relative burden of property tax to non-residential classes.[xiii]

Any Future Increase in the Assessment Rates Would Still be Subject to TABOR and Have to be Voted on by the People but the State Legislature Could More Easily Lower Rates or Expand the Non-residential Property Base

The constitutional amendment known as TABOR, requires that any tax rate increase in Colorado be first approved by the voters directly. Under the current Gallagher Amendment, any forced rate reduction by the state Legislature to the non-residential property, would likely lead to a reduction in the residential assessment rate as the formula would require that the share of residential assessed property value remain nearly constant.

However, if Amendment B passes, the repeal of the Gallagher formula would mean that lawmakers could elect to reduce either the non-residential or the residential assessment rate without concern for triggering some unintended response from the current formula. This observation does not suggest whether such a measure would be positive or negative, rather simply that it would seemingly be easier to accomplish than it is currently.

What Are the Likely Impacts if Amendment B Fails?

If Amendment B fails, then future impacts would be driven by current law. It is important for voters to understand that just because the law governing property taxes would remain unchanged, that doesn’t mean there would be no near-term or longer-term impacts.

Current State Estimates Indicate the Residential Assessment Rate Will Need to Drop to 5.88% Next Year

Due to the economic fallout from actions taken in the midst of COVID-19, commercial property value, particularly related to oil and gas, are expected to fall significantly. At the same time, residential property values have held steady and even grown in some areas. The resulting impact is that the according to an analysis prepared for lawmakers, the Gallagher formula, which resets property tax assessment rates every two years, is expected to reduce the residential assessment rate from 7.15% to 5.88%.

Despite steady, or even growing, residential property values, the lower assessment rate is expected to reduce local property tax revenue by $700 million. Of the total, $491 million is estimated to from K-12 education funding by and $204 million from funding for county services.[xiv]

This significant reduction in taxes for residential property taxpayers also represents a significant cut in funding for certain government services. The sharp reduction in revenue for local government services because of a declining assessment rate has historically prompted several reactions. Two of the most significant reactions addressed in the following sections include;

- An increase in general fund revenue contributed towards K-12 education in-order to backfill against the declining local share.

- An increase in local mill levies to offset the declining assessment rate.

Increase in General Fund Dollars to Schools to Offset Reduction in Local Property Taxes

If the residential assessment rate triggers cuts as predicted, the reduction in school district and local government revenue would be harder for state lawmakers to backfill due to severe budget limitation imposed by the COVID-19 recession. At the same time, any additional state funding would be distributed according to a school finance formula that has been shown to benefit wealthier school districts over poorer school districts, meaning extra state support may not go where it is needed most.

Through modeling provided by the DOLA in early May, is possible to estimate the potential impacts on school district revenue as a result of the declining residential assessment rate. With the current assessment rate of 7.15%, residential property tax revenue to local school districts grew by $741,498,178 or 15.04% in 2019. With the projected reduction in the assessment rate to 5.88% the annual growth in local school district revenue would have been $255,889,690 or 5.19%. Yet, while the property tax revenue collections would be positive across all school districts, the drop in the assessment rate would actually cause school district revenue across 26 counties to see negative revenue growth, while others remain positive. Given the different growth rates in the underlying property values, counties including Mesa, Pitkin, Park and Alamosa would have experienced lower property tax revenue than in 2018. The large caveat here is that some districts may have the ability to raise mill levies to offset the drop in the assessment rate, however those impacts are discussed in the next section.

Under Colorado’s School Finance Act, reduced property tax revenue at the local level for K-12 schools would increase the long-term demand for state education funding. However, as the Common Sense Institute has previously observed in the August 2019 report, “Dollars and Data: A Look at K-12 Education Funding in Colorado”, an overall statewide increase in K-12 spending does not guarantee that the school districts most in need will receive sufficient funding to backfill their losses. The existing school finance formula can, in some instances, send more state dollars to wealthier districts than poorer school districts, because the formula can overcompensate areas with higher costs of living.[xv]

Under Colorado’s School Finance Act, reduced property tax revenue at the local level for K-12 schools would increase the long-term demand for state education funding. However, as the Common Sense Institute has previously observed in the August 2019 report, “Dollars and Data: A Look at K-12 Education Funding in Colorado”, an overall statewide increase in K-12 spending does not guarantee that the school districts most in need will receive sufficient funding to backfill their losses. The existing school finance formula can, in some instances, send more state dollars to wealthier districts than poorer school districts, because the formula can overcompensate areas with higher costs of living.[xv]

Further Increase the Tax Burden on Non-Residential Property

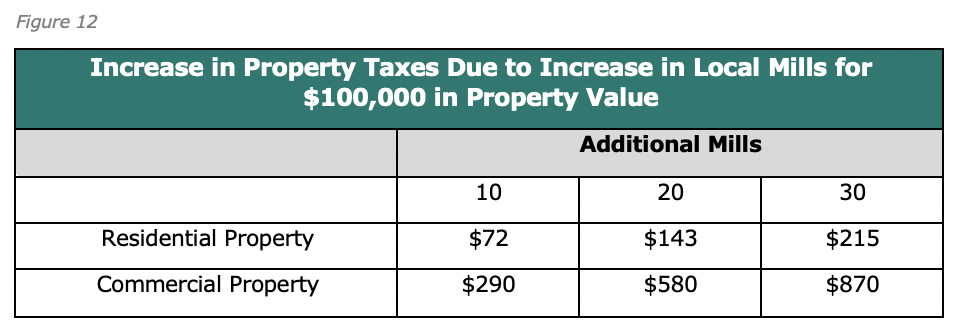

While the non-residential assessment rates have effectively stayed constant since the 80s, when the residential assessment rate falls and local mill levy rates increase, non-residential property gets hit harder than residential. The table below shows this effect for every $100,000 in residential or commercial property value across increases of 10, 20 and 30 mills. It shows that for every 10 additional mills, residential property pays an additional $72 dollars compared to commercial which pays an additional $290.

While an increase in mill levy rates requires a vote of the people in many jurisdictions, a growing number of taxing jurisdictions already have approval to automatically raise mills in response to lost revenues under the Gallagher Amendment. While the exact number of jurisdictions with automatic mill levy increases has still to be determined, and requires further research, preliminary research suggests this practice is relatively widespread, with examples including the Arvada Fire Protection District,[xvi] the South Suburban Parks and Recreation District and the Telluride Hospital District.

These automatic increases are known as “floating” mill levies, and while they are designed to keep residential property taxes relatively stable, they also trigger significantly higher property tax increases on businesses and other non-residential property owners. For example: Under a residential assessment rate of 5.88% and a non-residential assessment rate of 29%, the impact of a mill levy increase will be almost 5 times greater for a business than for a homeowner.

The Need for Longer-term Solution

Discussion surrounding the desire to change the state’s current property tax system have been circling for just about as long as the Gallagher Amendment has been law. Whether Amendment B passes or fails, it is argued the state’s property tax formula will still be in need of overhaul.

If Amendment B passes, it will mean that some local governments, primarily in more rural counties, will avoid the challenges of a declining residential assessment rate. Yet in the long-run, households will pay more in property taxes as their annual tax burden will be determined by the appreciation in the value of their home, as issue more acute in urban housing markets.

If Amendment B fails, the anticipated drop in the statewide residential assessment rate, will save homeowners money, yet will exacerbate the existing trends brought on by the current property tax formula. The sharp decline in local property tax revenue will likely lead to further crowding out of general fund dollars to backfill K-12 education funding, and lead to a steadily increasing property tax burden on non-residential properties.

One important area of Colorado local property taxation that will remain unaddressed regardless of the outcome of Amendment B is the complex network of policy surrounding special districting. Special taxing districts exist to fund specific activities. They often form to raise taxes that are used to pay the debt on the new infrastructure for new developments, yet they lack a lot of the same reporting transparency of other taxing jurisdictions. Given they have become a larger share of property taxation, this is a crucial area for future reform efforts.

All public policies inherently come with trade-offs. Developing the best system for taxing property throughout the State of Colorado is no different. Amendment B would both establish and avoid, several differing economic impacts important for Coloradans to consider. These tradeoffs should also clarify why a long-term solution will still be needed regardless the outcome in November.

[i] Department of Local Affairs Division of Property Taxation Annual Report, 2019: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QyS0LzOrYeygHMH9dDfR2UYw0J5-apJ8/view

[ii] https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/gallagher_amendment_memo_-_final.pdf

[iii] Colorado Department of Local Affairs, November 26, 2001. TABOR, Gallagher and Mill Levies: https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdelib/tabgallandmillspdf

[iv] Alternatives to the Gallagher Amendment Interim Study Committee, October 2018: https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/summary_report_to_legislative_council_1.pdf

[v] Legislative Council Staff Memorandum, July 30, 2020: https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/gallagher_amendment_memo_-_final.pdf

[vi] The assessment rate for oil and natural gas produced in Colorado is 87.5% as opposed to 29% for other kinds of commercial property. For a detailed examination of the property tax structure that applies to the oil and gas industry, please review the Common Sense Institute’s November 2019 report, The Local Revenue Impacts of Near-Term Oil and Gas Development: https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/local-revenue-impacts-oil-and-gas/

[vii] Joint Budget Committee Presentation of Colorado Property Tax Administrator JoAnne Groff, May 12, 2020: http://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/property_tax_05-12-20.pdf

[viii] The Denver Post, Oct. 30, 2018: “We’re way past the crisis point”: Property tax law putting lives in danger, Colorado fire chiefs say https://www.denverpost.com/2018/10/30/tax-law-gallagher-lives-danger-colorado-fire-chiefs/

[ix] South Platte Sentinel, May 29, 2018: Commissioners seek Gallagher fix https://www.southplattesentinel.com/2018/05/29/commissioners-seek-gallagher-fix/

[x] The Colorado Sun, July 7, 2020: Now that Colorado lawmakers have put Gallagher repeal on the ballot, will they actually be able to pass it? https://coloradosun.com/2020/07/07/gallagher-amendment-repeal-ballot-measure-pass/

[xi] NFIB, August 8, 2018: Is the Gallagher Amendment Killing Your Business? https://www.nfib.com/content/news/colorado/is-the-gallagher-amendment-killing-your-business/

[xii] Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, June 2020: 50-State Property Tax Comparison Study https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/50-state-property-tax-comparison-for-2019_full.pdf

[xiii] Colorado Department of Local Affairs, November 26, 2001. TABOR, Gallagher and Mill Levies: https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdelib/tabgallandmillspdf

[xiv] Joint Budget Committee Presentation of Colorado Property Tax Administrator JoAnne Groff, May 12, 2020: http://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/property_tax_05-12-20.pdf

[xv] Common Sense Institute, August 28, 2019: Dollars and Data: A Look at K-12 Education Funding in Colorado https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/k-12-education-funding/

[xvi] https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CO/Jefferson/91809/Web02.222611/#/cid/76