ABOUT THE AUTHORS

2022 Criminal Justice Fellows

George Brauchler

George Brauchler served as the elected District Attorney for the 18th Judicial District, Colorado’s most populous district, which includes Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert, and Lincoln counties, from 2013-2021. As a state prosecutor, he handled the felony cases from the Columbine High School mass shooting case, the Aurora Theater (Batman) mass shooting case, and more recently, the STEM Academy school mass shooting case.

Mitch Morrissey

Mitch Morrissey served as the elected District Attorney for the 2nd Judicial District covering Denver, Colorado from 2005-2017. Prior to 2005, Mitch was a trial lawyer in the Denver District Attorney’s office. Mitch is internationally recognized for his expertise in DNA technology and applying that technology to solve crimes. He has trained law enforcement officers and prosecutors throughout the United States, the Middle East, Central America, and Canada.

Chris Brown

Chris Brown is the Vice President of Policy and Research with the Common Sense Institute where he leads the research efforts of CSI to provide insightful, accurate, and actionable information on the implications of public policy issues throughout the state of Colorado.

Alexa Eastburg

Alexa Eastburg is a Research Analyst with Common Sense Institute. Her experience covers analyzing workforce, crime, and education issues in the state of Colorado.

ABOUT COMMON SENSE INSTITUTE

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

TEAMS & FELLOWS STATEMENT

CSI is committed to independent, in-depth research that examines the impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI’s commitment to institutional independence is rooted in the individual independence of our researchers, economists, and fellows.

At the core of CSI’s mission is a belief in the power of the free enterprise system. Our work explores ideas that protect and promote jobs and the economy, and the CSI team and fellows take part in this pursuit with academic freedom. Our team’s work is driven by data-driven research and evidence. The views and opinions of fellows do not reflect institutional views of CSI. CSI operates independently of any political party and does not take positions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to give a special acknowledgement to Dr. Ted Miller of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation in Beltsville, Maryland. Dr. Miller and his co-authors’ 2021 article in the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, “Incidence and Costs of Personal and Property Crimes in the United States, 2017,” served as the foundation for the estimates on the cost of crime in Colorado. Dr. Miller was gracious with his time and expertise to ensure we appropriately replicated his methodology while account for differing data constraints.

Introduction

In December 2021, Common Sense Institute Criminal Justice Fellows Mitch Morrissey and George Brauchler issued a study on the crime wave impacting Colorado. At the time, complete 2021 crime statistics for the state were not yet available. According to the Colorado Crime Statistics, there is a two-month lag in data entry. For example, complete December 2021 data was not available until March 2022. The CSI 2021 report “The Colorado Crime Wave: An Economic Analysis of Crime and the Need for Data Driven Solutions” included data through August 2021. This follow-up report adds in data from September through December of 2021, covering all 12 months.

The undeniable and blistering increases in crime in Colorado continued throughout 2021. The impact is greatest on the growing number of victims. However, the full costs of crime are borne by all Coloradans through public tax dollars, lost economic opportunity and diminished quality of life.

CSI’s December 2021 report significantly heightened awareness of the problem among the public, policymakers, and the media. Evidence of major changes to pre-trial bonding, the state’s correctional population, and the rates of individuals being arrested multiple times, pointed towards reduced accountability throughout the criminal justice system. The data demonstrating Colorado’s crime wave remains undisputed.

So, what can be done? Colorado’s lawmakers successfully confronted out of control crime in the 1990s. The time has come to do so again.

CSI’s December 2021 report included the following recommendations:

- Colorado should establish a public-facing data dashboard that can help analyze the connection between crime and the offenders who are in some way connected to the criminal justice system. The data that currently exists is not well-known, is dispersed, difficult to acquire, and not readily available for timely analysis by the public or policymakers. What percentage of Colorado’s spike in crime is committed by first-time offenders, prior arrestees/convicts, those on bond (personal recognizance or otherwise), probation or parole, and other categories? These important questions are answerable, but at present not easily so.

- Colorado should monitor and study the costs and benefits of public safety policy reforms over the past decade and current criminal justice trends, and then assess the unintended consequences of policy changes.

- Given the growth in organized retail crime, in conjunction with the online sale of stolen items, Colorado should establish a multi-agency task force to help with the challenges of investigating and prosecuting crimes occurring over multiple jurisdictions with a focus on identifying higher ranking offenders in the organized crime unit.

- To reverse some of the recent trends, Colorado must start with an honest conversation about our current situation. Then we must engage in the policy challenge of weighing the tradeoffs inherent in establishing the rules of Colorado’s society, and then fairly and effectively enforcing them.

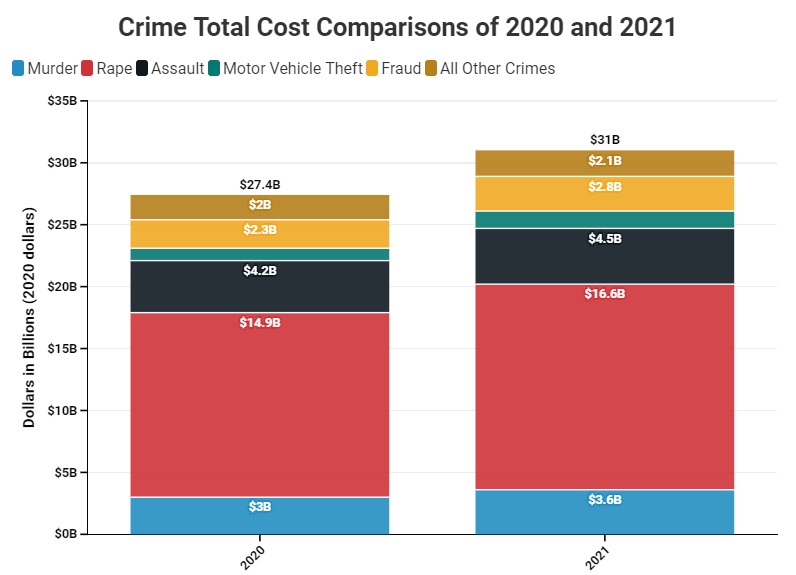

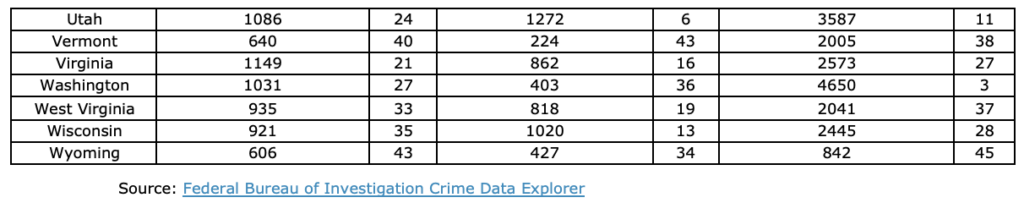

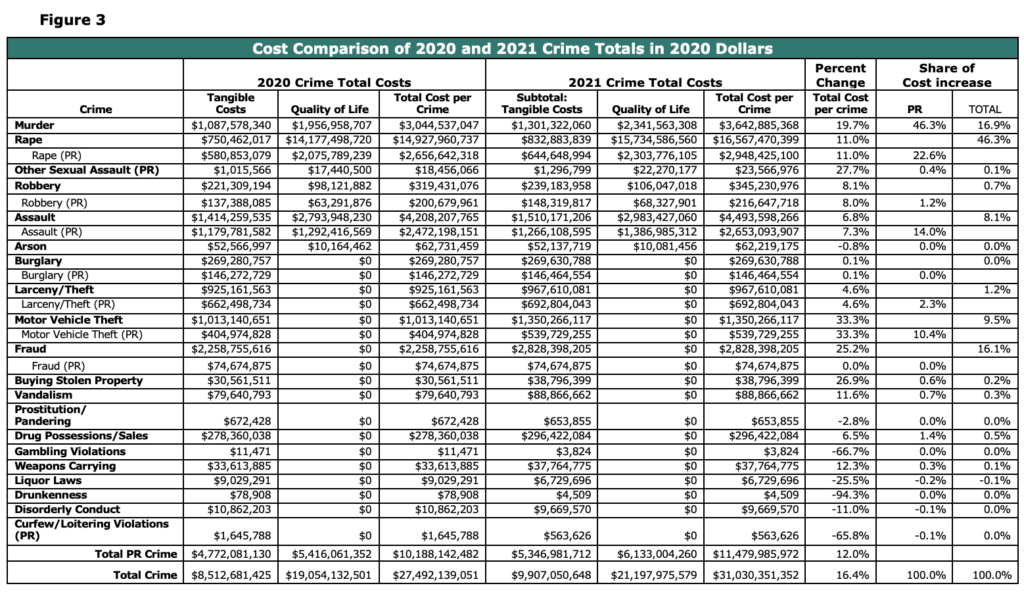

The cost of crime in Colorado in 2021 totaled $31B. This was an increase of $3.5B, or 12.9%, from the cost in 2020, primarily driven by the increases in violent crimes.

- The cost of crime in 2021 per Coloradan was over $5,320, an increase of almost $560 per Coloradan.

- The largest contributors to the increase in costs were higher rates of murder, rape, fraud, motor vehicle theft and assault.

- The single crime category with the most significant impact on costs was rape. The increased cost to Coloradans in reported rapes was $1.6B or 46% of the total annual cost increase.

- Murder across Colorado increased by 18% in 2021, costing Colorado an additional $600M. Both the number and rate of homicides in 2021 was the highest on record, dating back to 1985.

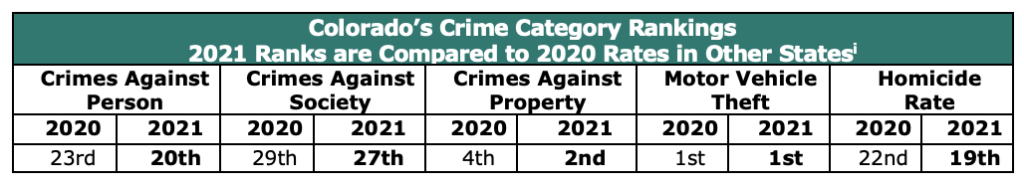

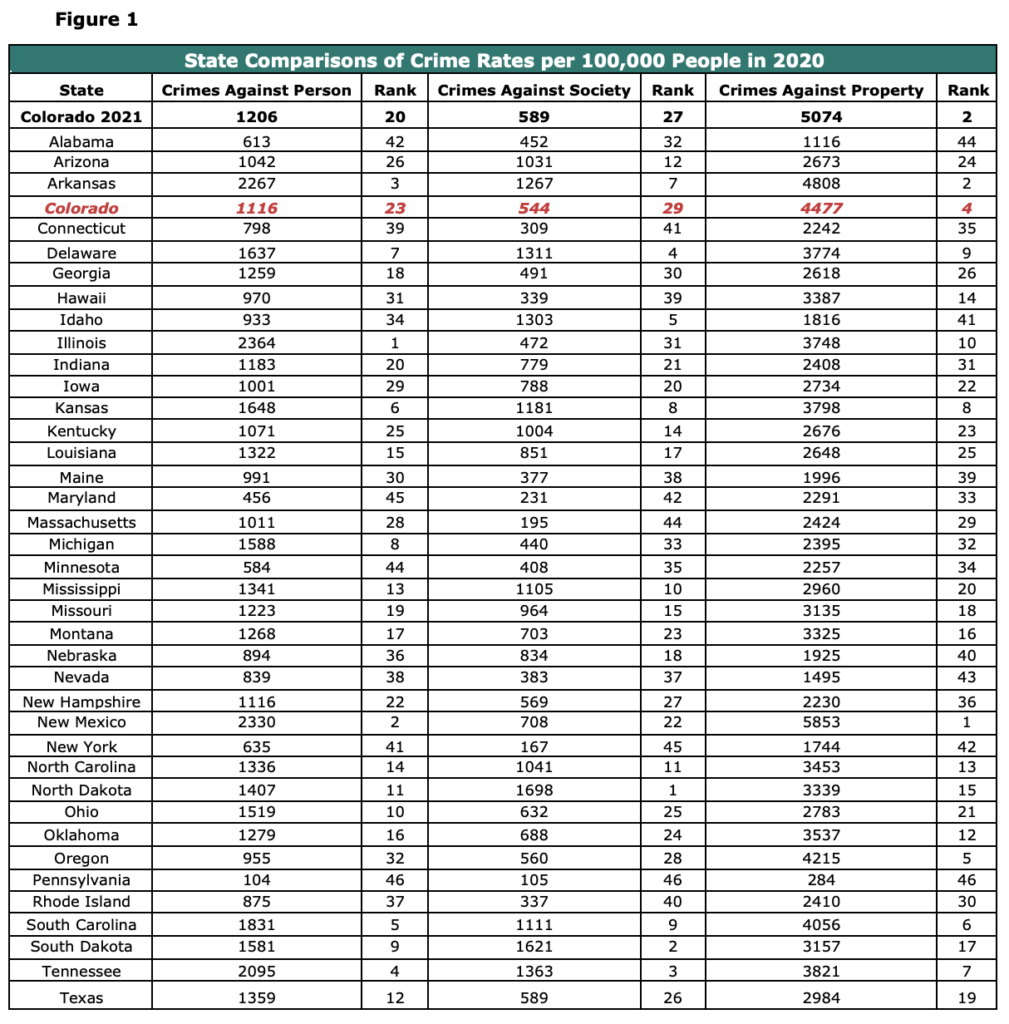

- In 2020, Colorado ranked 4th worst in the U.S. for its property crime rate. Colorado’s 2021 property crime rate would have ranked 2nd worst among all states in 2020.

- In 2020, Colorado led every other state in America with the highest rate of motor vehicle theft. One year later, Colorado’s rate increased by 33%, costing Colorado citizens $1.35B in 2021.

- The 2021 surge in motor vehicle thefts continued a trend which started in 2014. The legislature should evaluate how reducing the statutory consequences for motor vehicle theft in 2014 has impacted subsequent and significant increases in this crime.

- The trends across Colorado’s criminal justice system point towards reduced accountability. The costs and connections between a declining jail population, increased personal-recognizance (PR) bonds for serious crimes, and growth in multiple arrests of the same individuals, must be better understood.

- The 2021 crime numbers reinforce the need for policy leaders in Colorado to engage in the important work of identifying and understanding the impact of public policy on crime and its cost to Colorado’s communities. Lack of substantive actions to review and assess impacts, is creating costs beyond just crime. Over the past two years, Colorado has experienced one of the fastest growing rates of fentanyl related deaths, increasing from 222 in 2019 to over 800 in 2021. Despite growing calls for a legislative fix to a 2019 law decriminalizing drug possession of up to 4 grams of a narcotic, including fentanyl, as of the release of this report, no such legislation has been introduced.

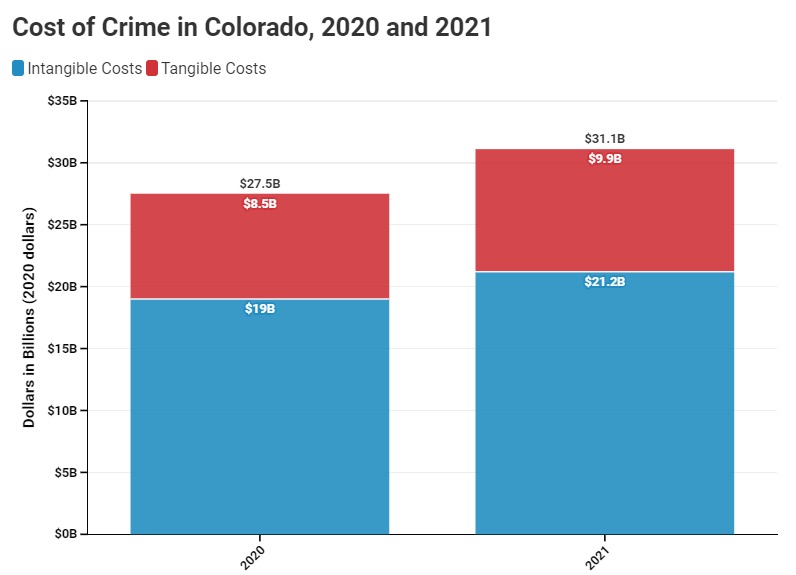

2021 Cost of Crime in Colorado

The 2021 paper titled “Incidence and Costs of Personal and Property Crimes in the United States, 2017,” published in the journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, estimated the total cost of crime in the United States to be $2.6 Trillion in 2017. In consultation with the primary author of that paper, Dr. Ted Miller with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), and the use of his cost of crime model calibrated for Colorado, the 2020 cost of crime in Colorado was estimated to be $27B as published in CSI’s December 2021 report.

Using the same cost of crime model, with updated data published by the Colorado Crime Statistics through March 4th, 2022, the total cost of crime in Colorado for 2021 grew by 12.9% to $31.1B. Increasing the 2021 cost of crime per Coloradan to $5,320.

To avoid capturing the record levels of inflation over the previous 14 months, the 2021 cost of crime estimate is given in 2020 real dollars. Therefore, it is directly comparable to the 2020 cost of crime estimate as it does not include higher underlying price levels.

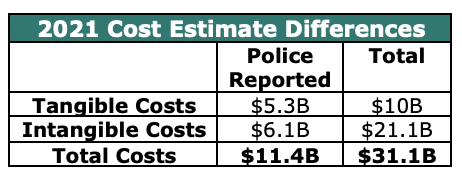

The total cost of crime is a sum of seven categories of tangible costs and one of intangible costs.

Tangible cost categories:

- Medical

- Mental Health

- Productivity

- Property Loss

- Public Services

- Adjudication and Sanctioning

- Perpetrator Work Loss

Intangible cost category:

- Quality of Life

The intangible costs of crime account for 68% of total costs. While these costs don’t measure a direct transaction value, they do measure the relative costs borne by victims of crime and those in higher crime areas, who suffer negative consequences related to behavioral decisions and mental health.

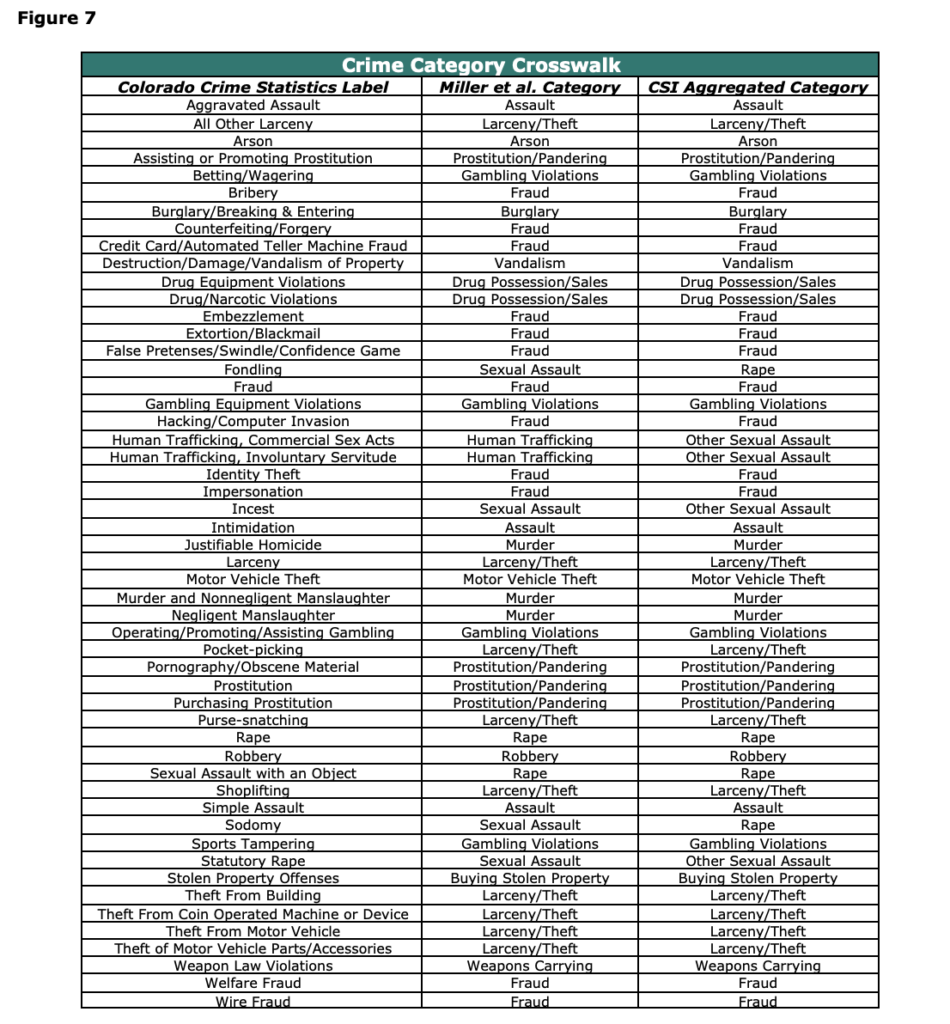

The crime counts from the Colorado Crime Statistics webpage captures police reported crimes. The cost of crime model includes crime specific adjustments to estimate the number of crimes not reported to police. Thus, the total cost of crime estimates includes the cost to victims and society of crimes not reported.

Figure 2 in the Appendix shows the relationship between police reported and total crime counts. The largest difference in these categories includes sexual assaults and fraud.

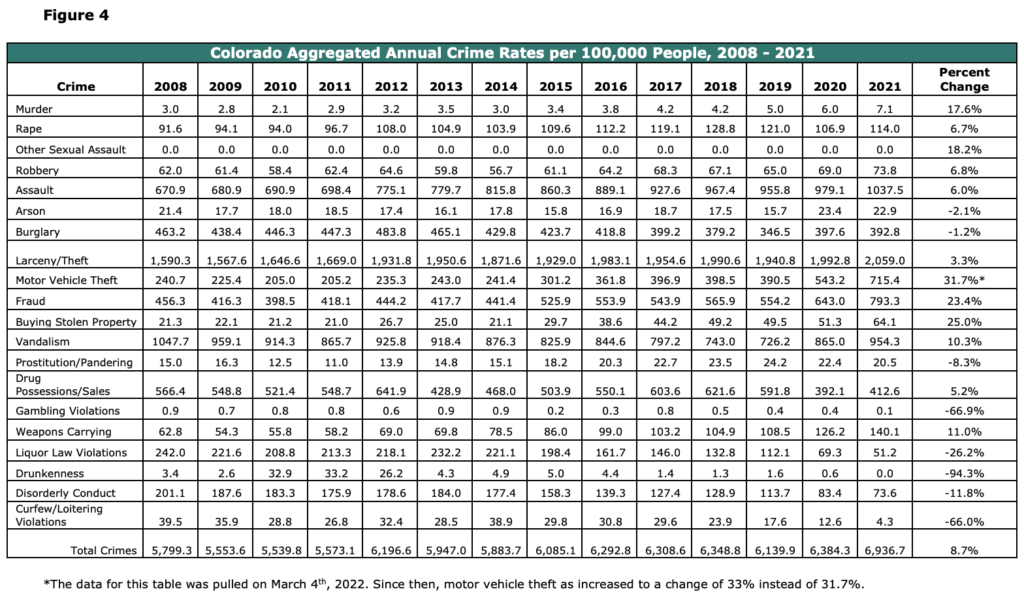

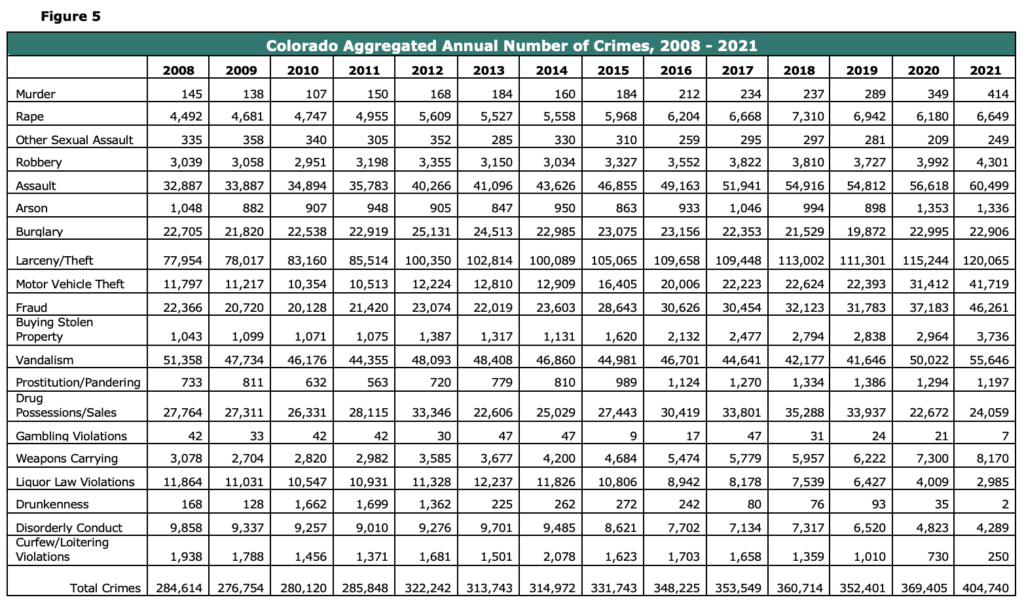

2021 Crime Rates in Colorado

The 2021 crime rates as reported through December 31st, 2021, were pulled from Colorado Crime Statistics webpage on March 4th, 2022. The data reflects a concerning and unabated increase in crime across Colorado. The total, population adjusted crime rate, reported as the number of crimes per 100,000 Coloradans, increased by 8.7% in 2021, more than double of 2020’s 4% growth rate. The combined two-year increase in Colorado’s overall crime rate since the start of the pandemic is 13%.

The Colorado Crime Statistics releases data related to crimes in Colorado on a rolling basis. There is an approximate 60-day reporting window from law enforcement agencies to the public website, equating to a two-month lag in more complete monthly data. The FBI will report the 2021 figures later in the year, therefore the estimates of crimes through December 2021 used in this report are viewed as preliminary, yet likely very close to the final figures.

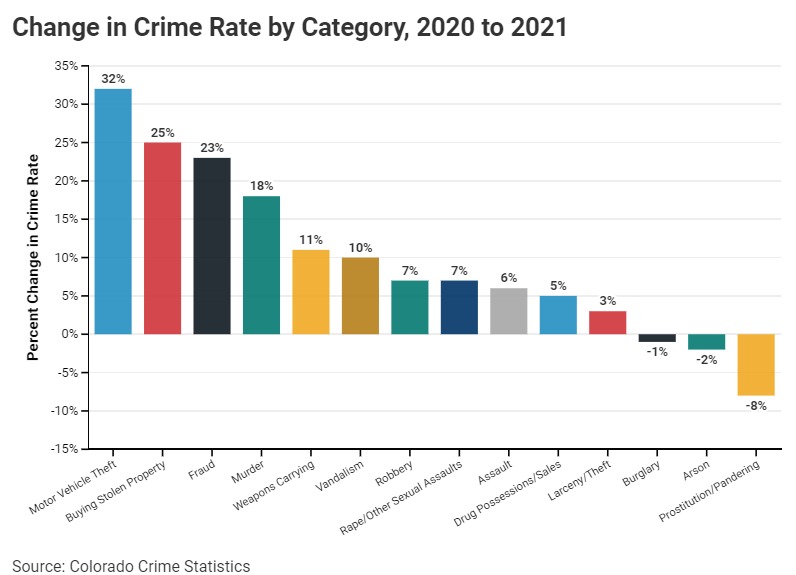

While the overall increase in crime rates was significant, the change across categories of crimes varied

Key Findings on Colorado Crime Rate Changes

- The motor vehicle theft rate climbed another 32% in 2021, ranking it as the highest annual rate of motor vehicle theft since 1985, when the FBI began keeping such records. While Colorado already had the highest motor vehicle theft rate among all states in 2020, the 2021 increase pushed the rate to be nearly 250% higher than a decade ago and 83% higher than 2019.

- After a decline in 2020, the 2021 rate of rapes increased by 7%. While the rate increased, the 2021 rape level was still below levels experienced between 2017 and 2019.

- Both arson and burglary declined in 2021, after increases in 2020. The 2020 increase in the burglary rate was the first since 2005 in Colorado and remains near the historic low in 2019. Although the arson rate is nearly 1/3 of its peak in the late 1980’s, it remains at its highest point since 2008.

- The murder rate increased by 18% in 2021. Relative to 2019, the rate increased 43% as there were 145 additional murders. Though Colorado’s homicide rate was below the national average in 2020, the 2021 rate (based on the Colorado Crime Statistics data) would have been above the US average and is the highest rate in Colorado since the FBI began recording such data in 1985.

Crime Across Colorado Counties

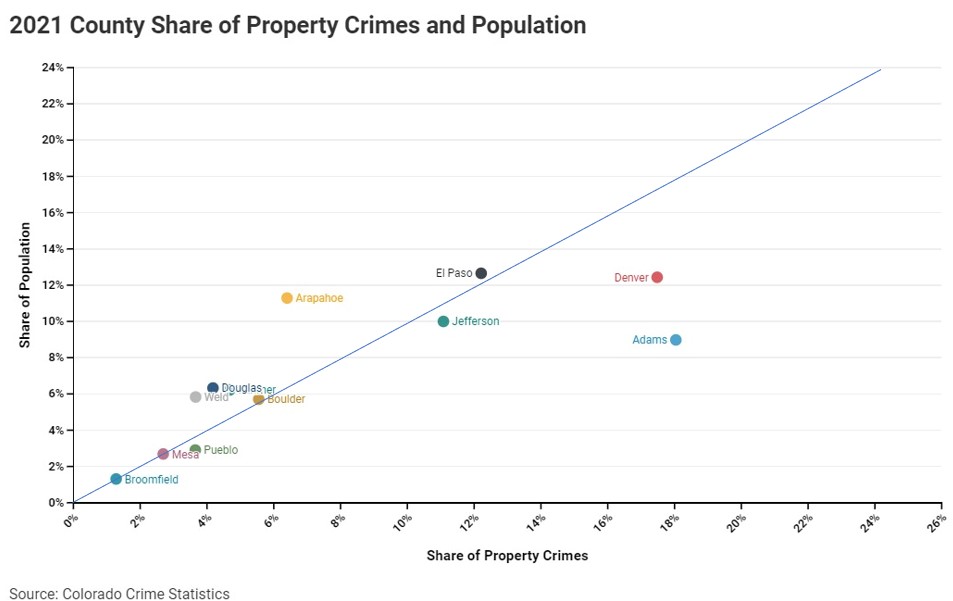

86% of Colorado’s 2021 population residing in the 12 most populous counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver, Douglas, El Paso, Jefferson, Larimer, Mesa, Pueblo, and Weld. Yet those same counties are home to 93% of the property crimes (including 97% of all motor vehicle thefts), and 89% of crimes against a person, which includes violent crimes.

The charts below contain more details across counties, however there are several important insights to note.

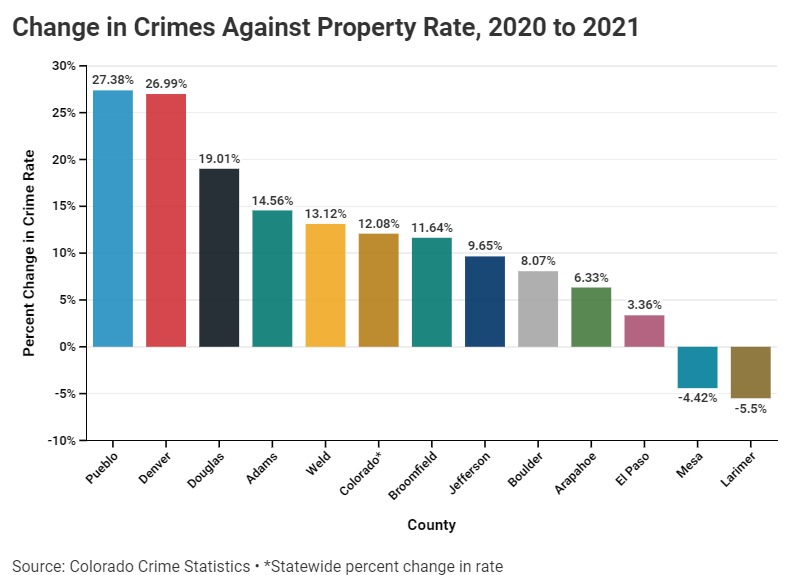

- While Pueblo saw the fastest increase in property crimes, 27.4% in 2021, its share of total property crimes remained at 4% of Colorado’s total. Denver experienced the second highest increase in property crimes, 27% in 2021, and given its relative population size, its share of statewide property crimes increased from 17% to 20%. While 1 in 8 Coloradans live in Denver, 1 in 5 property crimes occur there.

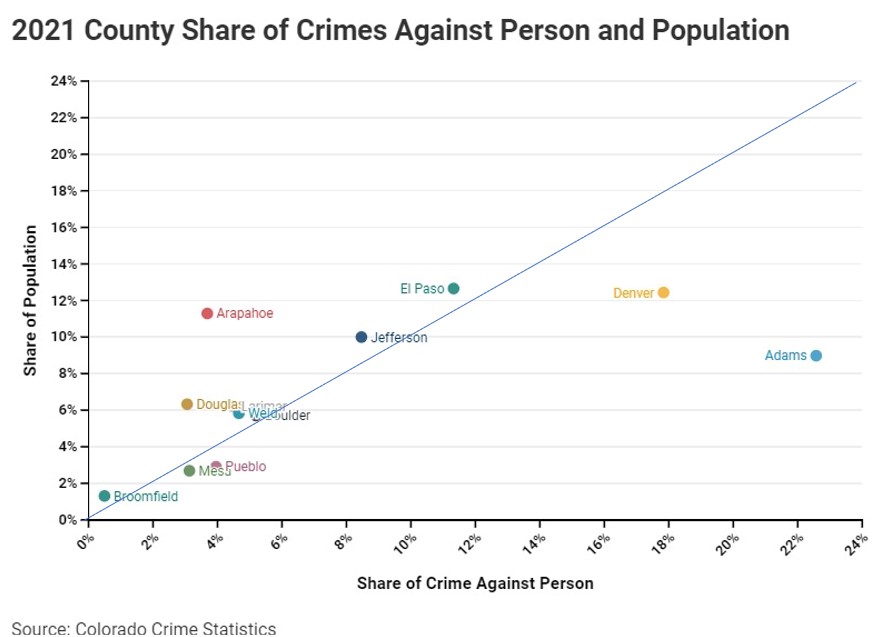

- Adams County had the highest share of crime relative to its share of population. It had 9% of the state’s population in 2021 yet had 19% of the crimes against property and 23% of the share of crimes against person.

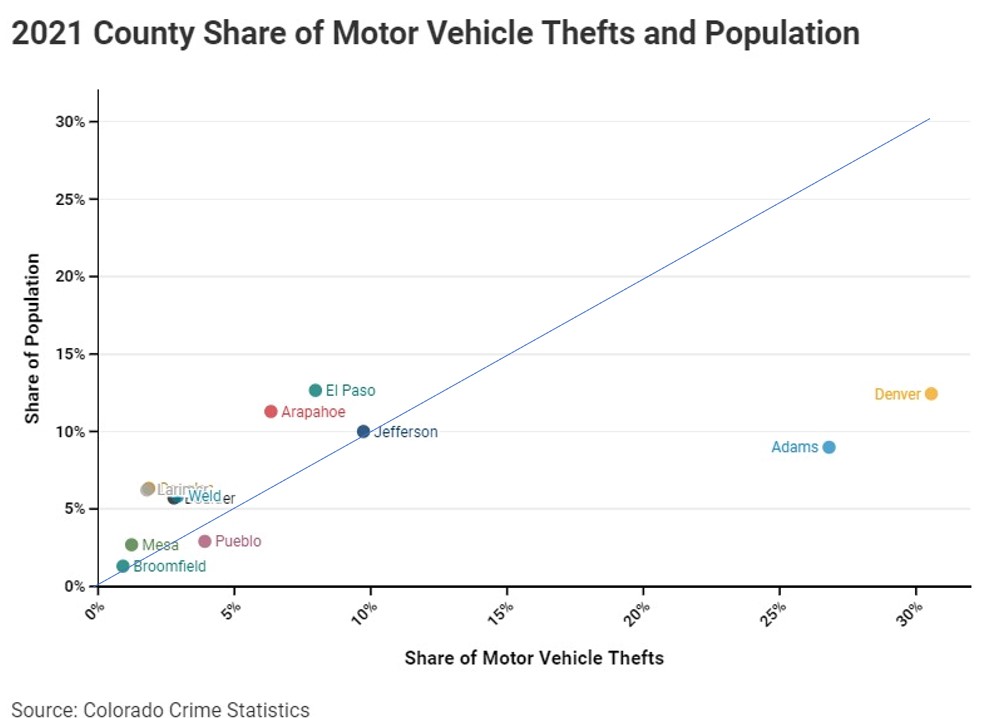

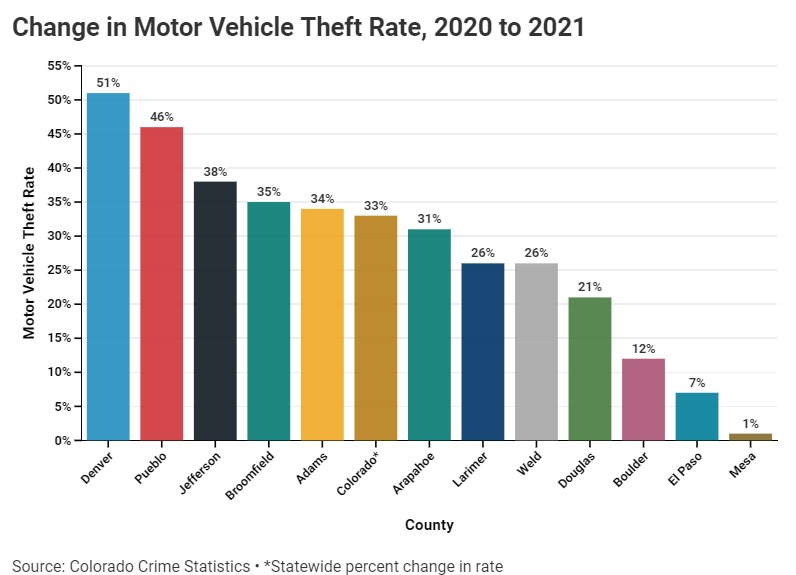

- In 2021, Denver led the state with the fastest growing rate of motor vehicle theft at 51%. Despite making up 12% of Colorado’s population, Denver accounted for 41% of motor vehicle thefts in the state.

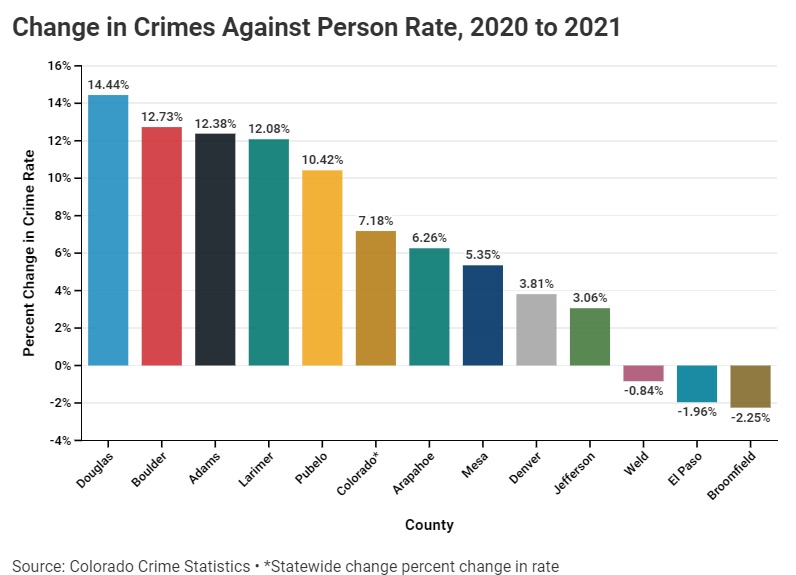

- Only El Paso County, Weld County, and Broomfield County experienced rates of crime against a person decline in 2021, while Mesa and Larimer were the only to experience a decline in their property crime rate.

The Colorado Crime Statistics definition of Crimes Against Person include the following crimes: assault, homicide, human trafficking, kidnapping/abduction, and sex crimes.

The figure below shows the share of each county’s population and their share of crimes against person. Counties above the blue line have a higher share of population than share of crime and counties below the line have a higher share of crime than share of population.

Five of the twelve counties analyzed had a growth rate in their crimes against person above the state average, while seven fell below. Only three counties experienced a decrease in the rate as shown in the figure below.

Similar to the rate of crimes against persons, crimes against property rose in 2021, though at nearly twice the rate. Both Pueblo and Denver experienced a rate increase of approximately 27%, more than double the statewide average rate of 12%. Just two counties, Mesa and Larimer, experienced a decline in their property crimes rate.In 2021, Adams and Denver County had 21% of the state’s population, yet 54% of all motor vehicle thefts. Pueblo is the only other county that has a higher share of motor vehicle theft than population, though to a much less degree than Adams and Denver counties.

In 2021, Adams and Denver County had 21% of the state’s population, yet 54% of all motor vehicle thefts. Pueblo is the only other county that has a higher share of motor vehicle theft than population, though to a much less degree than Adams and Denver counties.

Each of the 12 counties reviewed experienced an increase in their motor vehicle theft rate, although the range varied widely. While the motor vehicle theft rate only increased by 1% in Mesa County, it grew by more than 30% in 6 counties, including 46% in Pueblo and 51% in Denver.

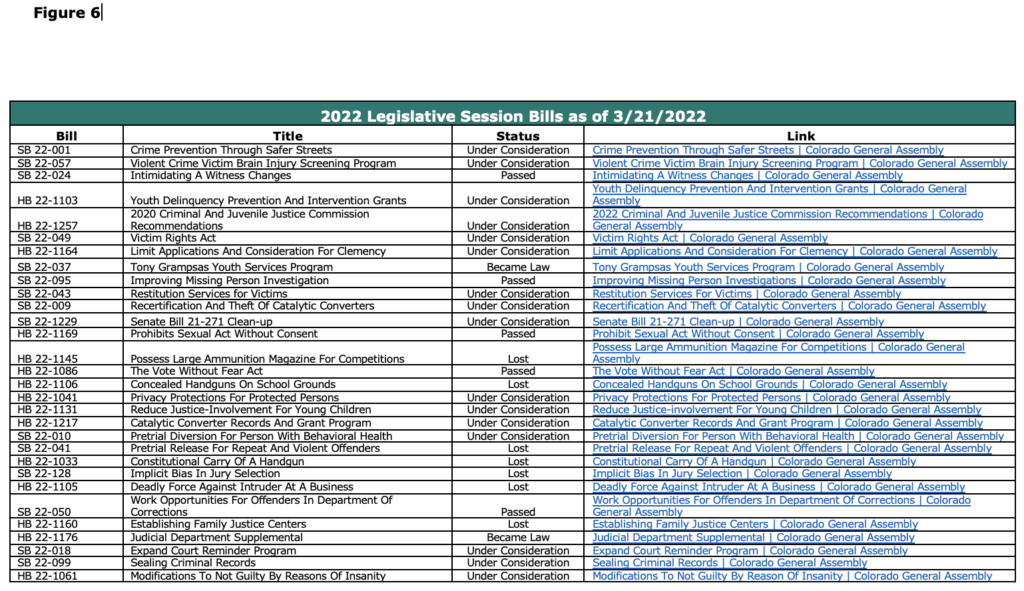

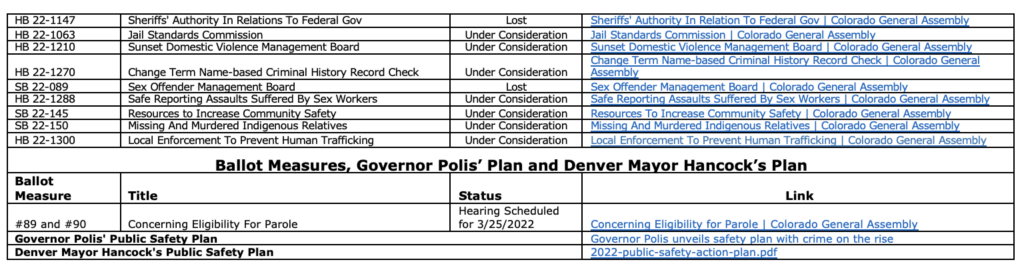

State Policy Response to Rising Crime Rates

CSI’s December 2021 report highlighted several changes within the Colorado criminal justice system, that could be key contributors to the rising crime rates in Colorado.

Those documented and concerning trends included:

- Declining prison and correctional population relative to – and concurrent with – increasing crime rates.

- Increase in personal recognizance bonds and $0 or $1 bonds for violent charges.

- Increasing number of individuals with multiple arrests within the past 12 to 36 months.

The report’s primary solutions offered in previous report included both the evaluation of policy impacting the areas that are showing concerning trends, along with the creation of a public-facing data dashboard that displays the extent to which criminal offenses are being committed by individuals who were previously connected to the criminal justice system.

Since the release of the December 2021 crime report, another important trend has come to light, rising to the forefront of the policy discussion. With the 2019 decriminalization of certain drugs, including the highly potent and lethal drug of increasing prevalence fentanyl, there have been growing calls to revisit this law, and its impact on the growing opioid related public health crisis and growing crime rate.

HB19-1263 titled the “Offense Level For Controlled Substance Possession” decriminalized the possession of four grams or less of a Schedule II controlled substance, including fentanyl, from a felony to a misdemeanor.

The most immediate and predictable impact of the law has been a significant decrease in the number of criminal cases filed in district courts. In 2020, the first year of the change in the law, the number of new criminal cases filed declined by 7,544 or 15%, as the number of new drug cases fell by 7,552 or 59%.

In the cost of crime analysis, there are many areas of cost that are not included in the model. This is especially true when it comes to discussing the public health and human costs of the use of illicit drugs. The social and economic costs that come with drug use, drug addiction, overdoses, and deaths related to drugs are substantial. Because the cost model does not take these types of costs into account, the overall cost of crime in Colorado is likely even larger than calculated in this report.

Legislation this session must be evaluated based on its potential to generate an immediate and meaningful impact on Colorado’s rising crime rates.

Appendix

© 2022 Common Sense Institute

[i] Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Data Explorer | National Incident-Based Reporting System

[i] Colorado Drug Overdose Dashboard | Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment

[i] HB19-1263 Offense Level For Controlled Substance Possession | Colorado General Assembly

[i] CCJJ: Criminal Justice Trends in Colorado (February 11, 2022)