The Latest Colorado Public Option Proposal Still Threatens the Jobs of Health Care Workers and May Trigger Higher Costs for Businesses and Households

About the Authors

Chris Brown is the Vice President of Policy and Research with Common Sense Institute where he leads the research efforts of CSI to provide insightful, accurate and actionable information on the implications of public policy issues throughout the state of Colorado.

Erik Gamm is a Research Analyst with Common Sense Institute where he supports the research efforts of CSI. Erik recently graduated from the University of Michigan in 2020 with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Economics.

About Common Sense Institute

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

Key Findings

- The introduction of HB21-1232[i] marks the third attempt in less than 18 months to design a public option health plan for Colorado. While the newest version of the public option proposal has some updates, it does not avoid the economic impacts and unintended consequences of earlier proposals. As a result, HB 21-1232 would likely have serious consequences for Colorado’s health care sector and the employer-sponsored health plans where most Coloradans obtain health care coverage.

- HB21-1232 would impose top-down government price mandates for health care services in Colorado, without actually lowering the cost of delivering those services. As a result, payments to doctors, nurses, hospitals and other health care providers for treating patients could be cut by $830 million to $1 billion by 2024.

- These revenue losses reflect the unpaid costs of the public option plan. These unpaid costs do not disappear, however. They must otherwise be paid in two principal ways: Spending cuts across the health care sector or cost shifting to other health care consumers, especially those in employer-provided insurance plans.

- Spending cuts of $830 million to $1 billion per year in Colorado’s health care sector would result in the loss of 3,900 to 4,900 health care jobs, including doctors, nurses and other professionals involved in patient care.

- To avoid these job losses, health care providers could instead shift $830 million to $1 billion in unpaid costs from the public option to consumers with employer-provided health insurance. The higher costs for these consumers and their employers would negatively impact the broader Colorado economy, resulting in the loss of 4,300 to 5,400 jobs across all industries.

- Through government price mandates and the creation of a new quasi-state entity to run the public option in the state’s individual and small-group insurance markets, HB21-1232 undermines the private health care plans and private health care systems that provide coverage and care to most Colorado households.

- Physicians, nurses, acupuncturists, chiropractors, midwives, and many other health care providers would be compelled to participate in the public option and treat patients at artificially low, government-determined reimbursement rates. Providers who cannot afford to treat patients at these low rates or otherwise choose not to take part in the public option would be threatened with disciplinary action, including the loss of their license to treat patients.

- Hospitals, community clinics and other facilities would similarly be forced to participate in the public option or risk losing their ability to treat patients. Under HB21-1232, state health officials would be authorized to “suspend, revoke or impose conditions on a health facility’s license or certificate of authority” if those facilities fail to comply with mandated participation in the public option.

- HB21-1232 directs the private health care sector to reduce average insurance premiums in the individual and small-group markets by 20% below 2021 levels within two years in order to avoid the creation of a public option that directly enforce this price mandate. However, the bill fails to account for inflation, population growth and other costs that influence medical cost trends. This effectively results in a government price mandate of 35% below the baseline premium level in 2024. Even after the impacts of Colorado’s new reinsurance program are accounted for, revenue losses of this magnitude will likely result in a combination of health care sector spending cuts, premium increases for consumers in traditional private health plans, and job losses.

- Failure to meet the government price mandate would trigger the introduction of the public option in 2025. To run the public option, HB21-1232 creates a new “instrumentality of the state” called the Colorado Option Authority to administer and sell the government-controlled health plan in direct opposition to the private sector. This violates the principles of free enterprise that underpin Colorado’s economy and also conflicts with a general prohibition in Colorado law against state agencies providing goods or services to the public in competition against private enterprise. At a minimum, the creation of a new state-controlled insurance plan that can force the participation of health care providers and force those providers to accept below-market rates for their services is a significant threat to the private health plans that cover most Colorado households and raises serious public policy concerns.

Introduction

On March 18, 2021, HB21-1232 – the Colorado Option Health Benefit Plan – was introduced in the state legislature. This marks the third major attempt in less than 18 months to design a state-controlled health care plan, commonly called “the public option,” for Colorado. Since the first attempt in 2019, the Common Sense Institute (CSI) has produced a series of reports examining each new iteration of the proposed public option in Colorado. The 2020 CSI report on the impacts of the public option proposed at the time, included detailed modeling supported by actuaries at the global consulting firm Guidehouse.[ii] CSI has also produced research on the implementation of a public option in Washington State, which is the first state in the nation to attempt such a policy.

This study, the sixth CSI has produced on the public option concept, reviews HB21-1232 and its potential impacts both within the Colorado health care sector and across the broader state economy.

The authors of HB21-1232 may have attempted to mitigate the impacts of previous public option proposals, but the fundamental approach remains the same: Legislating lower prices without lowering actual costs. This results in unpaid costs from the public option that must be covered by others, in the form of higher prices, reduced access and reduced quality of care.

As such the potential consequences for the state’s health care system and broader economy continue to be serious, especially after the damage and long-term uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The following findings summarize the impacts and primary policy challenges given the current design of the HB21-1232.

Background on the Public Option Debate

Proposals to create a public option have existed at the federal and state level for more than a decade.

While the details of different proposals may differ, they share a fundamental approach. Under a public option, officials create a government-controlled insurance plan which offers significantly lower premiums compared to those being offered in the private insurance market. To support these below-market premiums, the public option mandates that physicians, nurses, hospitals, and other health care providers treat patients with the new plan at reduced government rates. Those rates are set significantly below the level health care providers are paid by private insurance carriers, and are usually benchmarked against Medicare or Medicaid, which are social safety net programs for senior citizens and low-income households respectively.

At the federal level, the public option was considered during the debate over the Affordable Care Act in 2009 and 2010. It was ultimately rejected, however, by Congressional leaders and the Obama-Biden Administration. More recently, in the lead up to the 2020 presidential election, the public option concept received renewed attention.

A number of candidates in the Democratic presidential primary called for the creation of a federal public option. One of those candidates, Washington State Governor Jay Inslee, went further by signing a public option bill into law in Washington State less than three months after launching his presidential bid. Today, the Washington State public option, known as Cascade Care, is currently in its first year of operation. The performance of the Washington State public option relative to Colorado’s efforts to reduce premiums in the ACA’s individual marketplace will be addressed later in this report.

The Democratic primary and the 2020 general election were ultimately won by President Joe Biden. As a candidate, President Biden also called for the creation of “a public health insurance option like Medicare” at the federal level. However, it currently remains unclear how much priority the Biden administration will give the public option in Congress.[iii] In the recently passed American Rescue Plan Act, for example, Congress and the Biden Administration prioritized the expansion of federal tax subsidies for households that purchase health plans in the ACA’s individual marketplace.

In Colorado, a 2019 law – HB 19-1004 – directed state agencies to study the public option concept and submit a report with recommendations to the state legislature. This report, completed in November 2019, was followed by the introduction of a public option bill, HB 20-1349, in March 2020 – shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic triggered lockdowns across the state and forced the legislature into a lengthy adjournment. In early May 2020, CSI published a study which found approximately 4,800 health care workers could lose their jobs under the public option created by HB 20-1349, among other economic impacts

As the May 2020 study was going to press, the authors of HB 20-1349 announced they would not pursue their bill during the remainder of the 2020 legislative session. Following the abandonment of this effort, in March 2021, an updated public option proposal was introduced in the state legislature: HB21-1232.

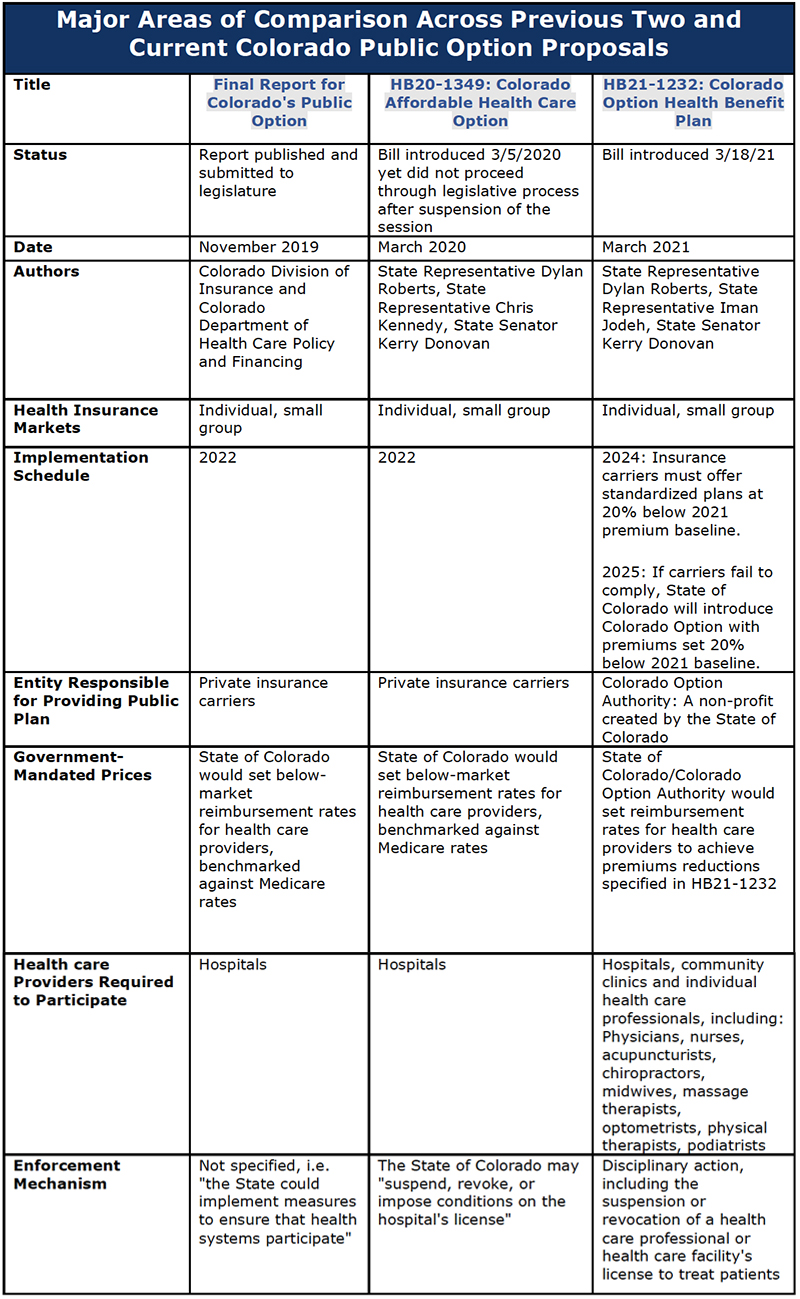

The following table summarizes the major design elements of the three public option proposals and how those elements have changed between November 2019 and March 2021:

How Does HB21-1232 Compare to Previous Public Option Proposals in Colorado

By viewing the major design elements of these proposals together, the most recent proposal–HB21-1232–can be viewed in context and its significance better understood.

Compared to public option earlier proposals, HB21-1232 has more expansive and more aggressive government pricing mandates. What began as mandated pricing of health care services has become mandated pricing for both health care services and insurance premiums, including percentage targets that would be written into statute.

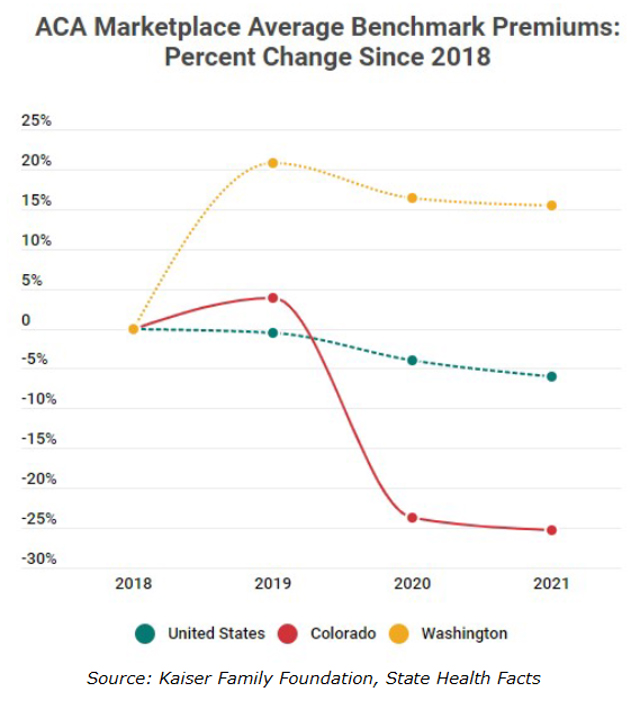

- Since the passage of legislation to study the public option in Colorado insurance premiums in the individual market have come down 30%[iv]. Individual insurance markets were significantly disrupted following the passage of the federal Affordable Care Act and the expansion of Medicaid. As a result, premiums were very volatile for several years. However, since 2018, individual insurance plan premiums have fallen 6% nationally, as markets have stabilized. Colorado prices have outperformed the national average falling over 30% since 2019. This is primarily driven by the creation of a new state reinsurance program, funded by fees on insurance companies and hospitals as well as redirected federal dollars. These significant premium reductions have occurred while Colorado’s health care industry has continued to rank high in terms of quality and access. According to US News and World Report state rankings, Colorado’s health care ranking improved from 12th to 10th from 2019 to 2021.[v] This sizable reduction has also outperformed Washington State, which despite being the first state in the nation to implement a public option proposal, have seen premium increases of more than 15% since 2018. Colorado’s benchmark premiums are now 9.5% lower than those of Washington State.

Under HB21-1232, the state government also has a more direct role in implementing the public option. While earlier versions of the Colorado public option would have been administered by private insurance carriers, HB21-1232 would create a new “instrumentality of the state” called the Colorado Option Authority to operate the new government plan. This would put a state-sponsored entity in direct competition with the private sector, using government-mandated pricing to undercut the premiums offered by private health plans. This is a major departure from the standing rule in Colorado law that prohibits the state from offering “goods or services to the public which are also offered by private enterprise” unless otherwise authorized by law.[vi]

In addition to creating an exception to this prohibition, HB21-1232 also attempts to indemnify the state against the financial risk posed by creating and selling its own insurance product. The bill states “debts and liabilities of the [Colorado Option Authority] do not constitute the debts and liabilities of the state.” This appears to be an acknowledgment of a warning contained in the Polis administration’s November 2019 report on the public option, which cautioned that the state should not “carry risk as a health insurer” and instead rely “on licensed insurance carriers to administer the plans, hold the financial risk and manage provider contracting.”

Several very large and important questions remain surrounding the creation and funding of a new state authority.

- How much funding is needed for administration and reserves for new state authority to act as an insurance agency?

- Is there sufficient savings available through federal premium tax credit reductions to cover costs? And if not, will the state use federal funding from existing reinsurance program to cover new authority costs, further increasing the cost pressures on private carriers?

- If the state does not bear the risk of the new state authority, who does, and will the authority face the same regulations as private carriers?

Finally, compared to past versions of the Colorado public option, HB21-1232 threatens to sanction a much larger number of health care providers if they do not agree to participate in the new government plan – up to and including revoking the licenses that allow them to treat patients. Earlier versions of the Colorado public option attempted to force participation from health systems and individual hospitals with the threatened loss of their operating licenses. But HB21-1232 would amend the professional conduct laws of many different health care providers to make participation in the Colorado public option effectively mandatory.

Failure to participate in the public option would subject individual health care professionals to disciplinary action – and HB21-1232 directs these sanctions at a long list of providers. Targeted health care facilities and individual health care professionals include hospitals, community clinics, doctors, nurses, acupuncturists, chiropractors, midwives, massage therapists, optometrists, physical therapists and podiatrists.

Therefore, HB21-1232 would authorize a much larger government intervention into the state’s health care sector than previous iterations of the Colorado public option. The expansion of government control proposed under HB21-1232 would impact the state’s health insurance sector, the way health care providers are paid, and the licensing laws that determine whether certain health care facilities and health care professionals are allowed to see and treat patients.

Economic Impacts

The economic impact analysis conducted by CSI has consistently shown the central challenge with each iteration of the public option proposals including HB21-1232:

Mandating lower prices for a good or service does not make the underlying cost of providing that good or service disappear. Instead, such mandates create unpaid costs that show up somewhere else and ultimately still must be paid.

What are the impacts of trying to cut the price we pay for health care without changing underlying costs of delivering care? In the case of health care workers, the cost may be reduced hours, furloughs or job loss. In the case of employers and their workers, the cost may be higher insurance premiums or out-of-pocket expenses.

The following estimates were produced through a combination of two models. The direct revenue projections were developed using an Excel based model to capture the aggregate changes in health care expenditures from a forced reduction in insurance premiums and the resulting migration to the Colorado Option Plan. The economic impacts across Colorado employment were developed using the economic simulation model Tax-PI, developed by the company REMI. A description of both models is included in appendices.

- By 2024, health care providers in Colorado could see revenue cuts between $830 million and $1 billion. If these revenue reductions were to be borne 100% by the health care sector in the form of output losses, the cuts would result in the loss of 3,900 and 4,900 health care sector jobs, including physicians, nurses and other professionals involved in patient care.

- This would effectively ask Colorado health care providers to do more, with less, while they are attempting to recover from the staffing and budgetary stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Some sectors of the economy would benefit, given the increase in consumption from those who save on lower health insurance costs, however the net employment impacts across all industries remains negative, at between 1,300 and 1,700.

- To limit job losses, facility closures, and service reductions, health care providers may choose to pass the unpaid costs of HB21-1232 to privately-insured patients. This additional cost on job creators would slow overall economic growth and may result in net losses of 5,400 jobs across all sectors and $470 million in annual personal income.

- These impacts are the result of the state government mandating a 20% price cut in the individual and small-group insurance market from 2021 premium levels. Under HB21-1232, there are two methods for enforcing the 20% mandated price cut: Either the Colorado health care sector complies with the mandate by the 2024 plan year, or the State of Colorado carries out the mandate directly through the introduction of the Colorado Option in 2025.

- Colorado’s recent reinsurance program has cut health insurance premiums in the individual market by an average of nearly 21% in 2021. However, since HB21-1232 would require a 20% reduction in the nominal price from 2021, which does not account for inflation or medical cost trends, the required premium rate would be closer to a 35% reduction in prices relative to what premiums would have been in 2024 without reinsurance. Given the funding for the reinsurance program is currently not expected to expand, we assume that premiums will grow from current levels.

Impacts to Competition in Health Insurance Market

In addition to government-mandated pricing, there are several other elements of HB21-1232 that are contrary to the principles of free enterprise that undergird Colorado’s economy.

- HB21-1232 creates a pathway for a new state “authority” which would compete directly against private insurance carriers, while being granted a different set of rules than which govern those private carriers it would compete against. Under Colorado law, the state is banned from offering “goods or services to the public which are also offered by private enterprise” unless specifically authorized by law.[vii] While HB21-1232 may create an exception to the rule, the prohibition exists in state law for a reason and should not be overlooked or dismissed without proper consideration.

- HB21-1232 creates a two-step process of government price fixing over the Colorado health insurance market. Step 1 demands a 20% nominal reduction in ACA health insurance premiums within two years to prevent the Colorado Option from being offered by the state. If those price mandates are not met, the state would move to Step 2 and directly offer the Colorado Option with the government fixing premiums and provider rates for the new public plan at the mandated level.

- The bill compels individual health care professionals – including doctors, nurses, acupuncturists, chiropractors, midwives, massage therapists, optometrists, physical therapists and podiatrists – to participate in the Colorado Option. To ensure compliance, HB21-1232 authorizes disciplinary action against health care professionals with, including the revocation of their license to treat patients, if they do not accept the state option plan offered by state authority.

- Hospitals, community clinics and other health care facilities are also compelled to participate in the Colorado Option. As with individual health care professionals, HB21-1232 would allow state officials to “suspend, revoke or impose conditions on a health facility’s license or certificate of authority” as a penalty for non-participation.

- The bill grants the new state authority and its commissioner special considerations in their future rate setting process for certain providers, such as “critical access hospitals, rural and independent health-care providers and those health-care providers with a percentage of Medicare, Medicaid and uninsured patients that exceeds the statewide average and may consider the cost of adequate wages, benefits, staffing, and training for health care providers’ employees to provide adequate care.” While private insurance carriers would face the same challenges in reducing premiums through re-negotiating the rates they pay, there is no acknowledgement of those challenges or allowance for not achieving the required 20% premium cut.

- That specifics of what benefits will be included in the new Colorado Option Plan or “standardized plan,” are not yet known. Therefore, while private carriers will be judged based in ability to reduce future premiums against 2021 levels, the new “standardized plan” may include increased benefits which come at a higher cost.

- Recent trends in Colorado insurance markets question the need to move ahead with a major new public health care program, when premiums have already been reduced significantly using different policy and market mechanisms since the public option debate first began. Since 2018, when Colorado lawmakers first began pushing for the creation of a public option, benchmark premiums in the ACA individual market have fallen by more than 25% and are now the 6th-lowest in the nation.

Conclusion

The third and latest iteration of a public option proposal for Colorado once again relies on government mandates on prices and participation, a fact that should draw serious scrutiny about the long-term impacts it would produce for Colorado. Recent trends in insurance prices and significant state reforms passed just two years ago have caused average benchmark premiums in the individual market to fall 30% since 2019 when the public option debate emerged in the state. This has caused Colorado to improve its ranking from 27th to 6th lowest average premium among all states.

The health care crisis brought on by COVID-19 has caused an immense amount of uncertainty surrounding the health care sector’s future in Colorado. Physicians, nurses, hospital systems and other health care providers face real questions about how to repair the damage their sector has suffered during the pandemic. Given the economic modeling shows HB21-1232 could force an additional $1 billion per year out of Colorado’s health care sector, the imposition of not just new mandates but also the pending threat of cooperating with a new state authorized payer should be carefully weighed against the costs.

Getting the rules and regulations surrounding our shared health care sector right is critical for both the affordability and quality of the system our lives depend on. With many unanswered questions and the immediate need to recover from the economic fallout from a pandemic, we hope these costs and considerations are carefully weighed.

Appendix A: Model Methodology

The findings of this study, especially those concerning health care revenue and insurance markets, were generated using an original set of functions and linkages which CSI used to model the impacts of Colorado’s 2019 public option proposal and which have been updated and fundamentally reconfigured to reflect the differences of the 2021 bill. These are designed to illustrate the financial mechanisms of artificial reductions in health insurance premiums and the imposition of a state-run standardized health insurance plan: a cap on premium levels below their market-clearing prices lowers the prices paid to health care providers and drives up demand for insurance, which causes offsetting revenue effects from previously-insured people spending less on medical care and previously-uninsured people purchasing insurance for the first times. The parameters, sources, assumptions, and processes it includes are summarized here in moderate detail.

Baselines, Sources, and Inputs

Population figures, health insurance market information, expenditure data, and official silver premium prices (presented as averages weighted by regional populations) come from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Colorado Health Institute, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Colorado Division of Insurance, respectively. Some of these are manipulated by population projections or inflation history from the Colorado Demographer’s Office and the Bureau of Labor Statistics via the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, respectively. The parameters input manually to the model are the medical cost trend, the annual inflation rate, and the shares of people enrolled in the individual and small-group insurance markets willing to switch to the state option plan if it’s cheaper than their current plans.

Assumptions

These are the key assumptions under which the model operates:

- The medical cost trend will follow the post-pandemic national PWC-forecasted average annual increase of 6% (middle scenario) through 2025,

- Colorado’s consumer price index will increase by an average annual rate of 2.2% through 2025,

- Individual-market policyholders in 2021 pay 20.8% (according to the DOI) less in premiums than they would have if Colorado had no reinsurance program,

- Between 80% and 100% of enrollees in the individual and small-group markets will switch to state option plans if they are cheaper at the same levels of coverage than the average other plans,

- The share of uninsured people who will choose to purchase state option plans is reflected by the function f(x) ≈ ln((0.017327x) +1), where x is the percentage that the state option premium is lower than the average other individual-market premium, and

- The premium-reduction requirements and details of the standardized insurance plan are set as they are outlined in the introduced bill.

Model Processes

The purpose of the model is to extrapolate the parameters and inputs outlined above into static revenue and enrollment effects of [bill]’s implementation. It achieves this by establishing baseline trends of premium prices and populations that reflect estimated and assumed growth factors, developing dependent outputs based upon the bill’s provisions and the study’s scenarios, and calculating the differences between them.

From population-weighted and trend-adjusted averages of reinsurance premiums and pre-reinsurance premiums, enrollment levels, expenditure levels, and reenrollment assumptions, the model calculates state-option premiums in both relevant insurance markets, state-option enrollment, new regional uninsured rates, and the revenue impacts upon Colorado’s health care system that these would cause. Revenue impacts are aggregated based upon whence they derive and the health care operations to which they pertain; impacts from the individual and small-group markets are always negative, impacts from the uninsured population are always positive, and these in summation are distributed across seven aspects of the health care industry defined by KFF according to the relative sizes in Colorado that they comprise of the total industry less nursing care.

For forecast year 2025, the model can be adjusted to reflect either the insurance industry’s compliance with the bill’s rate-reduction ultimatum or its failure to prevent the establishment of the state authority and the state option plans. In the former case, 2025 premiums are allowed to increase from the required 2024 level by the one-year rate of inflation plus 1%; in the latter, 2025 state option premiums are set at exactly 20% below the pre-reinsurance 2021 level. This toggle alters only the 2025 results.

Dynamic Modeling

To determine the impacts of these static health care revenue losses upon the broader Colorado economy, CSI input them into the REMI Tax PI economic model under two scenarios: the cut scenario, in which the revenue changes are represented as cuts to health care spending and offsetting increases in non-health care spending, and the pass scenario, in which the revenue changes are represented as increases in costs for businesses and commensurate increases in non-health care spending. The Tax PI model, using REMI’s proprietary data and macroeconomic formulae, returns a list of quantitative dynamic impacts that the changes to the input variables would have upon industry-specific metrics such as employment and output, and economy-wide metrics such as GDP and labor force. All the employment figures in this report are outputs of the Tax PI model.

[i] http://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb21-1232

[ii] https://commonsenseinstituteco.org/co-option-plan/

[iii] https://www.politico.com/news/2021/03/16/public-option-health-care-biden-476458

[iv] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-benchmark-premiums/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=2018–2019–2021&selectedRows=%7B%22wrapups%22:%7B%22united-states%22:%7B%7D%7D,%22states%22:%7B%22all%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%222021%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[v] https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings

[vi] C.R.S. § 24-113-103 (Lexis Advance through all laws passed during the 2020 Regular and First Extraordinary Legislative Sessions and Measures approved at the November 2020 General Election)

[vii] C.R.S. § 24-113-103 (Lexis Advance through all laws passed during the 2020 Regular and First Extraordinary Legislative Sessions and Measures approved at the November 2020 General Election)