View a pdf of this document

922 kb pdf

Executive Summary

The federal debt now exceeds $14 trillion and continues to grow at a staggering pace with no end in sight. The record levels of debt have renewed the national conversation about the urgent need to get control of mandatory government spending obligations.

The debate that has resurfaced surrounding the dire necessity of entitlement reform is not one that is new to Washington, D.C., nor one that is even exclusive to federal lawmakers. In state capitols across the country, elected local leaders are looking for every available opportunity to tame their own ballooning entitlement expenses. The same growing wave of spending obligations that are engulfing the federal budget appear to be on course to drown state governments by seizing greater portions of their budgets – budgets that have already absorbed a tremendous blow from a prolonged economic downturn.

In Colorado, for nearly a decade, the state has faced an intractable structural budget shortfall, where government programs, services and operations have consistently grown at a pace faster than the state’s various revenue streams will support. Even after the enactment of a number of tax increase measures through the years, the sum total of which have brought in many hundreds of millions of new tax dollars, policymakers in Colorado have consistently labored with the task of finding sufficient state dollars to cover the exploding demands of certain government programs.

While conversations of Colorado’s budget dilemma inevitably invite debate about hot-button issues like TABOR, Amendment 23, Gallagher or other competing fiscal restrictions and spending requirements, the fact is almost no other taxing or spending driver has played a larger role in the state’s budget morass than the rapid year over year growth of Medicaid. Therefore, any talk of long-range budget solutions must include a meaningful and substantive discussion on reforming the state ‘s Medicaid system.

Consider these facts about the growth of Medicaid:

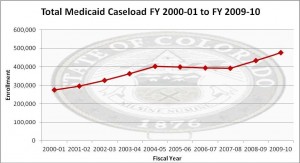

- In 2001, Medicaid caseload was roughly 275,000. As of August 2011, Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing reported that caseload is now over 597,000, representing more than 1 in 10 Coloradans.

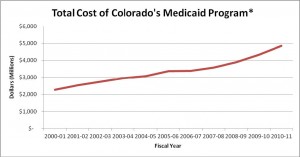

- The net budgetary effect of Medicaid’s upward march is readily obvious when evaluating the state’s spending bottom line. In fiscal year 2000-2001, total spending on Medicaid was just shy of $2.3 billion. Ten years later, total Medicaid spending has soared to nearly $4.9 billion.

- According to a study from the University of Denver, ten years ago education, corrections, and health care consumed about 54 cents of every General Fund dollar in Colorado. By 2009 that figure had grown to 76 cents, and is projected to grow to 91 cents in five years if the current spending trends continue.1 An ever-expanding Medicaid is a primary driver of this budget reality.

- In Colorado, even as Medicaid spending has soared, other core programs like higher education, transportation, and even recently K-12 education have experienced austere cuts. This is not a coincidence. With a flagging economy generating fewer revenues for the state, and Medicaid demanding more of the funding pie that is left, it is inevitable that the state’s roads and schools will suffer. Indeed, until Medicaid is reformed in a way that contains its fast-growing costs, Colorado’s systems of roads and schools will continue to experience a budgetary crowd out.

- Making matters worse, rapidly expanding Medicaid costs will be dramatically exacerbated by recently passed federal healthcare legislation. A requirement in the federal healthcare legislation requiring the state to cover everybody with an income under 133 percent of the federal poverty level, for example, will increase Colorado’s Medicaid population by over 44 percent by 2014.

These data points help illustrate the urgent need for Medicaid reform. The goal of this policy review is to clearly highlight the challenges presented by Medicaid that lay ahead, the various solutions being considered by other states, and to spark the conversation going forward that leads to a solution that fits the state of Colorado and her unique needs.

As Colorado’s elected leaders wade through the options in addressing the state ’s structural budget crisis, Medicaid reform must be a substantial part of that discussion and, ultimately, any solution.

To that end, CSPR believes that bold reforms of the state’s Medicaid system must be pursued. The first part of such a reform must begin with a broad-based and bipartisan approach to seeking a waiver from the federal government from the many strictures that would otherwise limit a meaningful change to the system in Colorado.

CSPR believes that the General Assembly and the Governor should immediately come together to craft the terms of such a waiver. The enactment of legislation seeking a waiver should be adopted, and signed, in 2011.

Achieving a truly meaningful reform of Medicaid will require innovative thinking and be dependent upon a good-faith effort from both political parties to work together. The reforms sought should aim to ensure Medicaid is available for those who need it most and achieved through a system that curbs waste, abuse and excess.

Medicaid vs. Medicare

It is not uncommon for these two programs to be mistaken for one another. Medicaid is ajoint state-federal program that provides health insurance for the poor. Eligibility forMedicaid is determined by income level and varies from state to state. States areresponsible for crafting and administering their own Medicaid program.

Medicare is a federal program that provides health insurance for almost everybodysixty-five or older. Medicare is administered by the federal government and eligibility is not tied to need. The rules are the same all over the country.

History of Medicaid

While state government balance sheets are not directly impacted by the soaring costs of Social Security and Medicare, they do share the uphill climb of reining in runaway Medicaid spending. Medicaid was created in 1965 as a federal and state partnership with the goal of providing medical coverage to low-income families. Under the watchful eye of Washington, each state was tasked with creating and administering their own Medicaid program that would meet the basic federal standards for service and eligibility. According to John D. Klemm, when Medicaid officially kicked-off in 1966 it cost less than $1 billion and covered roughly 4 million enrollees.

It did not take long before early outlay projections for Medicaid fell markedly short of reality. A combination of amendments passed by Congress, states exercising their ability to expand eligibility beyond the federal requirements, and a redefinition of the matrix used to determine eligibility conspired to lead Medicaid to grow at a hyper-accelerated pace. Klemm found:

“By 1971, annual spending had reached $6.5 billion, and enrollment had topped 16 million. Initial projections of Medicaid forecast less than one-half of this spending level, primarily because analyst greatly underestimated the extent to which States would offer coverage of optional eligibility groups – especially the medically needy and optional services.”2

In addition to the significant expansions being initiated by the states, a 1972 Congressional amendment creating the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which federalized an existing state-run assistance program for the aged, blind and disabled added a whole new category of Americans into the Medicaid fold. This new program fueled Medicaid‘s expansion as nearly all SSI beneficiaries were eligible to receive Medicaid coverage.3

“Driven by the growth in enrollment of persons with disabilities, total Medicaid enrollment grew at an average rate of almost 5 percent per year, and by 1976 it had reached 20.7 million.”4

By the early 1980s efforts to curb Medicaid’s rapid ascent were underway. In 1981, President Reagan put forward a plan to Congress to restructure the program as a block grant, which would have created a cap for federal matching funds.5 President Reagan’s block grant proposal was ultimately stalled in Congress. However, through the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 (OBRA-81), Reagan was successful in creating the Freedom of Choice waivers and the Home and Community-Based Services waivers which gave states the ability to better manage their Medicaid program.6 These waivers ultimately allowed states to better utilize managed care and provided more flexibility in services to the elderly and disabled.

Early efforts to restrain Medicaid were undermined midway through the 1980‘s as expansions once being offered by states voluntarily one-by-one became federal mandates. The Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1986 (OBRA 86) required states to cover emergency medical needs for illegal immigrants otherwise eligible for Medicaid, and gave them the option to offer Medicaid coverage to pregnant women up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level and infants up to a year old. In 1987 this option was expanded to include families with incomes of up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level, and just two years later the option became a mandate for all pregnant women and children under the age of 6 in families falling below 133 percent of the federal poverty level.7

The litany of new mandates coming from the federal government had begun to create so much strain on state budgets that in August of 1989, the bipartisan National Governors Association (NGA) sent a resolution and corresponding letter to Congress pleading for a two year freeze on any further Medicaid mandates.

“Dear Members of Congress: Today the Nation’s Governors took action calling on Congress and the White House to adopt a two year freeze on the enactment of further Medicaid mandates. Our Resolution was based on our increasing concern with the impact of the last three years of Medicaid mandates on our budgets, and consequently our ability to properly fund education and other important services.”8

The appeal to Congress from the state’s chief executives apparently fell on deaf ears as less than one year later Congress was already imposing a host of new mandates through the passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA 90). OBRA 90 required Medicaid coverage for children ages 6 to 18 in families with incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty level. By the mid 90s the GOP led Congress once again renewed effort to fundamentally restructure Medicaid by converting the program into a block grant – the proposal was ultimately vetoed by President Clinton, however.

In 1997, this trend of expanding Medicaid continued, and in dramatic fashion, when Congress created the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP or CHIP) as part of the Balanced Budget Act. The goal of this new program was to provide coverage to children who did not qualify for Medicaid and whose families were under 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

The carrot for the states was that they received a greater level of federal funding than under Medicaid and had the latitude to use the funds in a variety of ways, as well as charge premiums and copayments as they saw fit.

In the final year of President Clinton’s administration, Congress also passed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment and Prevention Act, which allowed states to provide coverage to women with cervical or breast cancer regardless of income or resources at a greater federal matching rate.9

Much of the expansion to Medicaid during the first 10 years of the new millennia has come as a result of states looking for creative ways to expand eligible pools that allow them to draw greater amounts of federal dollars. Estimates today indicate that Medicaid will cover more than 69 million people in 2011 – a number that is projected to grow to over 100 million by 2021.10,11 The combined annual cost to the federal and state governments was estimated to be $381 billion in 2009 with states typically covering 43 percent of the annual cost. 12,13

Medicaid Growth in Colorado

Colorado’s fast-moving Medicaid growth mirrors the national trend – a trend that is forcing a greater share of limited state revenue away from priorities like education and into the ever- expanding rolls of Medicaid.

According to a study from the University of Denver, ten years ago, education, corrections, and health care consumed about 54 cents of every General Fund dollar. By 2009 that figure had grown to 76 cents, and is projected to grow to 91 cents in five years if the current spending trends continue.14 Medicaid spending, which now accounts for over 20 percent of Colorado’s General Fund revenue, is a significant reason for this growth.

In 2001 Colorado’s Medicaid caseload was roughly 275,000. As of August 2011, Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing reported that caseload is now over 597,000.

Figure 1:

Source: Colorado Legislative Council

Over the past decade, it has been the actions of the Colorado General Assembly and, to a lesser extent, the voters that have pushed Medicaid enrollment to record levels. From removing the asset test, which required proof of minimal assets to qualify for Medicaid, to the expansion of eligibility levels for childless adults, the state has incrementally and consistently expanded Medicaid eligibilities over the last decade. According to Colorado‘s Legislative Council, on 12 different occasions between 2001 and 2010, the state expanded Medicaid.

Two specific Medicaid expansions are illustrative of the impact this can have on the state’s finances.

In 2004, voters approved Amendment 35, allowing taxes to be increased on tobacco products in order to expand Medicaid eligibility for adults and children. The amendment to Colorado’s constitution required 46 percent of the newly generated revenue to cover the expanded caseload resulting from the increase in income levels. Since that time, a combination of less tobacco tax revenue than was originally projected, and the General Assembly not always using the funds for the intended purpose, has lead to an anticipated shortfall in available funds to cover the subsequent expansion in HB 05-1262.

In the same way, House Bill 09-1293, commonly referred to as the hospital provider fee bill, was enacted in 2009 as an effort to draw down more federal funds by expanding eligibility levels and using the new “fees” to cover the state‘s share of the increased burden. HB 1293 was recently scrutinized as the state was forced to significantly scale back the expanded coverage levels as the original costs anticipated from the expansion of eligibility were grossly underestimated.

The Denver Post reported that the number of people eligible for coverage was nearly three times what was initially projected and costs of insuring them was almost nine times original estimates.15

“The expenditure obligation is forecast to exceed allocated tobacco tax revenues by $77.3 million in FY 2011-12 and $86.9 million in FY 2012-13. It is expected to increase in subsequent years as Medicaid expenditures continue to rise while tobacco tax revenues are stagnant or falling.”16

While both of these Medicaid expansions were purported to be funded with “new dollars”, the predictable reality is that the “new dollars” were not sufficient to cover the new expenses. And, as is so often the case, other programs in the state budget – namely education and transportation – will likely suffer for it.

The net budgetary effect of Medicaid’s upward march is readily obvious when evaluating the state’s spending bottom line. In fiscal year 2000-2001, total state spending on Medicaid was just shy of $2.3 billion. Ten years later, total state Medicaid spending has soared to nearly $4.9 billion.

*Includes all sources of funding (state, federal and cash funds). Source: Colorado Joint Budget Committee Appropriations Report, FY 00-01 – FY 10-11

Drivers of Future Expansion

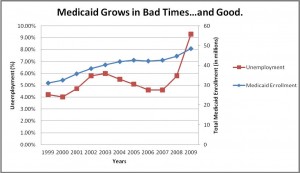

Looking back at the evolution of Medicaid since its inception, it would be difficult to point to any single change that led to its explosive growth. Instead, it has been the combination of federal and state policy changes that have contributed to the program becoming the bloated entitlement that it is today. There are a number of indications that the natural ebb-and-flow of the economy has also had an impact on Medicaid caseload, as well.

But the economic cycle, frequently pointed to as the chief cause for growth in Medicaid rolls, gets more credit for driving Medicaid caseloads than it should. Indeed, looking at the historical trend of the unemployment rate relative to the number of Medicaid recipients, you see an unmistakable trend: Medicaid grows in bad times and, frequently, in good times as well.

Figure 2:

Source: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics website

Looking forward, future growth in both caseload and total cost will be overwhelmingly driven by expansion resulting from the new eligibility levels mandated in the Patients Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA).

While other factors such as the rising cost of medical services and economic conditions will undoubtedly have an impact, the scale of imminent obligations contained in the PPACA will significantly outweigh all other potential areas of growth. Together, they will conspire to escalate Medicaid’s already exorbitant costs.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

In the spring of 2010, President Obama signed PPACA into law. The new federal law will hit full stride in 2014 and is expected to once again rapidly accelerate Medicaid spending by increasing costs to states by over $32 billion in the first six years.17 In an effort to lower the uninsured population throughout the country, the PPACA requires states to provide health care coverage to everybody falling under 133 percent of the federal poverty level through Medicaid. Unlike the current federal match for Medicaid, Washington promises to cover 100 percent of the new Medicaid recipients during the first two years. Starting in 2016, however, states will be required to cover 5 percent of the costs increasing up to 10 percent of the costs in 2020. Over time, then, this Washington mandate will shift more demand for a growing Medicaid to the already strained budgets of the states.

The American Legislative Exchange Council concluded that the requirement found in recently enacted federal healthcare legislation to cover everybody with an income under 133 percent of the federal poverty level will increase Colorado’s Medicaid population by over 44 percent by 2014.18 According to a recent University of Denver study:

“The State Department of Health Care Policy and Finance estimates that Colorado’s annual funding obligation will start at $30.9 million in FY 2016-17 and rise to $72.5 million by FY 2019-20.”19

While some proponents have hailed PPACA as a way for the nation to contain the costs of healthcare, such bold promises seem remote from the stark realities of the impact that federal healthcare legislation will have on Colorado’s budget into the future. Growth of state spending on Medicaid was a severe concern before the passage of federal healthcare legislation, and it is an even greater concern after.

The Crowd Out

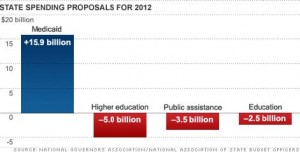

While the federal government is unencumbered by any requirement to have a balanced budget, states are forced to prioritize spending in order to stay on the right side of the ledger. The necessity for states to balance spending obligations with diminishing streams of revenue is bringing about the scenario that Americas Governors warned Congress about in 1989. A 2010 survey released by the National Governors Association and the National Association of State Budget Officers, reported that Medicaid now accounts for an average of 21 percent of state budgets.20

As future growth in Medicaid eligibilities continues to require an even greater percentage of state spending, lawmakers will undoubtedly face increasingly tough choices. The same survey reported that even as governors are searching for ways to deal with the rapid rise in Medicaid costs, they are being forced to make significant reductions to other parts of their budgets, including infrastructure, K-12 education and higher education.

It is estimated that in 2012, states will spend an additional $15.9 billion on Medicaid at the same time they are reducing funding for higher education by $5 billion and K-12 education by $2.5 billion.21 Former White House Office of Management and Budget director, Peter Orszag, suggested in a New York Times opinion piece that, “states tend to rob education to pay for Medicaid during economic downturns. And when the economy recovers, the money for education usually doesn’t get restored.”22

Figure 3:

Unfortunately for state policymakers, it does not appear as though relief is just around the corner. Medicaid enrollment is estimated to grow by another 3.8 percent in 2012, and by 17.3 percent over the next 3 years.23 Adding to the already challenging situation is the fact that federal stimulus money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which had pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into state coffers for Medicaid expenses, is now going away and forcing states to shoulder a heavier load.

In Colorado, this trend certainly holds true. Even as Medicaid spending has soared, other core programs like higher education, transportation, and even recently K-12 education have experienced austere cuts. This is not a coincidence. With a flagging economy generating fewer revenues for the state, and Medicaid demanding more of the funding pie that is left, it is inevitable that the state’s roads and schools will suffer.

Indeed, until Medicaid is reformed in a way that contains its otherwise fast-growing costs, Colorado’s systems of roads and schools will continue to experience a budgetary crowd out.

A recent study from the University of Denver’s Center for Colorado’s Economic Future painted an unwelcoming picture of Colorado‘s fiscal fortunes if a blind-eye is turned towards the growing problem.

The study’s forecast indicated that:

“From FY 2011-12 to FY 2024-25, General Fund expenditures associated with Medicaid medical services premiums are expected to grow at a compounded annual rate of 8.4 percent, going from about $1.3 billion to nearly $3.8 billion. That would be an increase from 17.9 percent to 27.2 percent of the net forecast General Fund revenues.”24

If the University of Denver forecast holds true, and Colorado reaches the point where Medicaid captures upwards of 27 percent of the state‘s annual budget, funding priorities such as K-12 education, higher education, public safety and others would suffer. Medicaid‘s current unsustainable growth rate is already beginning to crowd out these areas of the budget, and failure to tackle the issue now, coupled with the full enactment of the PPACA, will make a bad situation much worse.

Examples from Other States

Attempts to confront the mounting challenges created by the persistent growth of Medicaid are not unique to Colorado – not by a long shot. For over three decades now, Americans have heard from both local and national elected leaders that Medicaid is on an unsustainable path and must be reformed. In recent years, however, these words have started along the path to action, as certain states have taken a more aggressive approach, intensifying their efforts to secure greater flexibility and more local control from Washington.

These actions should provide a starting point for deliberations in the state of Colorado.

Rhode Island

In 2008, Rhode Island sought a sweeping global waiver from a host of federal restrictions, fashioned similar to a block grant that would provide the state significant flexibility to manage their Medicaid program. The proposed Rhode Island Global Consumer Choice Compact would restructure the state’s Medicaid program into a capped federal matching fund, with broad authority for state-driven reform. The 1115 waiver application submitted to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sought to create a “sustainable cost-effective, person- centered and opportunity driven program utilizing completive and value–based purchasing to maximize available serves options and a results-oriented system of coordinated care”.

Rhode Island’s Republican Governor, Donald Carcieri released a statement at the time of applications saying,

“Medicaid spending has increased drastically, and the current funding structure is forcing states to cut other critical programs, like education, highways and public safety or raise taxes significantly. This agreement will put us on a sustainable path for growth in Medicaid while also maintaining services for those most in need.”25

In January of 2009, Governor Carcieri‘s request for the global waiver was given the green light by the Bush Administration. Since implementation, projected Medicaid spending declined from $3.8 billion to $2.7 billion, according to Governor Carcieri‘s Office of Health and Human Services.26

Some of the key aspects of the Ocean State’s global waiver are an exemption from the federal “any willing provider” rule, the ability to assess co-payments, wellness and preventative care programs, the ability to allow seniors move into community and home care instead of more costly nursing homes, and a host of fraud prevention measures.

Washington State

As evidence of just how bipartisan the push for Medicaid reform has become, the State of Washington, led by a Democrat Governor and a Republican State Senator, pushed through a sweeping Medicaid waiver of its own. The Washington plan, signed by Democrat Governor Christine Gregoire earlier this year, closely tracks the broad-based waiver model first implemented in Rhode Island.

The bill, which passed the State Senate and Assembly with unanimous support, has only been controversial in that the right and the left have differed over what to call the plan. Conservatives have called it a block grant, a title at which Governor Gregoire rejects. For her part, the chief executive called it a plan that seeks “greater flexibility from the federal government by focusing on effecting purchasing and treatment.”27

If anything, though, the minor flap over how to describe the sweeping Washington-state reform, and the overwhelming bipartisan support that prompted unanimous passage of such a far- reaching measure, are both proof that old conventions and old partisan divisions are quickly becoming a thing of the past in those state’s that are serious about addressing the Medicaid crisis.

Illinois

Another example of a Governor reacting to the crippling weight of increased Medicaid spending amidst declining revenue is Illinois Governor Pat Quinn, a Democrat, who earlier this year signed his own set of reforms. The Illinois law was a two-step process initially focused on eliminating waste and abuse by requiring the state to pay Medicaid bills sooner to reduce late fees. It also increased the burden of proof for those who want to receive Medicaid benefits by requiring they provide a full months worth of paystubs rather than just a single paystub. The long-term goal of the Illinois legislation is to gradually move towards a managed care model.

The bill signed by Governor Quinn requires that half of Illinois 2.8 million Medicaid enrollees be moved into a managed care system by 2015. While these changes are not nearly as aggressive as the Rhode Island reforms, according to an AP story from January 2011, the Illinois reforms are estimated to save between $624 million and $774 million over five years.28

Florida

In Florida, a 2005 waiver requested by the Sunshine State kicked off a pilot plan that shifted the state’s role to a purchaser of care. The Florida waiver allowed the state to contract with multiple managed care providers. Each managed care provider that chose to participate was responsible for creating customized benefit packages that required state approval. The customized benefit plans for Medicaid enrollees had to cover the services mandated by state and federal law. If a Medicaid recipient was eligible to receive health benefits from their employer they could opt-out and apply their annual premiums to purchase employer sponsored insurance.

This year, the state of Florida expanded its managed-care pilot to the state‘s broader Medicaid program. While this move wasn’t without controversy, it still promises huge potential savings in the department of waste and fraud alone.

“By transitioning to managed care, the state will end what’s known as a “fee-for-service” system in which the state pays about 80,000 providers for each service they perform. More services mean more fees — and more cost. It also can lead to fraud — estimated at more than $1 billion — because the state pays first and asks questions later.”29

New York

Another state looking at the possibility of teaming with private managed care providers to cover Medicaid recipients in exchange for a monthly premium is New York. Earlier this year, newly elected Democrat Governor, Andrew Cuomo, commissioned a 27-member taskforce with a mission to reform the state’s Medicaid program which currently covers nearly twenty-five percent of the state’s population. The cornerstone of the taskforces recommendations was to transition Medicaid into a managed care program.

The common thread across many of these and other state-based Medicaid reforms is a shift to some form of managed care. Seventeen states already require some portion of their Medicaid enrollees to sign up for managed care.30

There’s a reason that a managed care option is gaining traction: Medicaid’s fee-for-service (FFS) system often places a perverse incentive on providing more care rather than better care. As reimbursement rates for providers are often atop the list of cuts for lawmakers, providers will often look for other opportunities to recover some of the declining revenue. Moving towards a managed care system where a patient’s care is monitored to ensure they see the right doctor and that unnecessary tests are avoided, ultimately leads to reduced costs while not sacrificing the quality of care.

In addition to curbing waste and abuse, a considerable share of the savings realized as a result of the managed care model has been from the coordination of services between physicians and specialists. Avoiding unnecessary office visits, tests or prescriptions, as examples, all result in lower overall costs while not jeopardizing the patients’ quality of care. Managing chronic diseases to minimize long-term care and lessening the dependence of emergency rooms are also critical parts of controlling costs that greatly improve in the managed care model. The State of Utah took steps this year to minimize emergency room visits by requiring a co-pay for patients who used ER’s for non-emergency related issues.

As a joint program between federal and state governments, Medicaid reforms will ultimately require leeway from Washington to the states. Successfully charting a course that reduces the long-term expenses, while protecting access to care, will require a thoughtfully crafted waiver. It will be important to clearly demonstrate where costs can be cut while also reassuring those who depend on the program that it will be there for them.

In sum, Colorado is not alone in confronting this overwhelming challenge. And in the case of Rhode Island, Washington State, Illinois, Florida and New York, the state of Colorado has several potentially effective models to emulate.

Solutions for Colorado

As Colorado’s elected leaders wade through the options in addressing the state’s structural budget crisis, it is important that the true drivers of the state’s spending imbalance be addressed. Any talk of long-range budget solutions must include a substantive discussion on reforming the state’s Medicaid system.

To that end, CSPR believes that bold reforms of the state’s Medicaid system must be pursued. The first part of such a reform must begin with a broad-based and bipartisan approach to seeking leeway from the federal government and the many strictures that would otherwise limit a change to the system in Colorado.

CSPR believes that the General Assembly and the Governor should immediately come together to craft the terms of such a waiver. The enactment of legislation seeking a waiver should be adopted, and signed, in 2012.

While numerous options and opportunities for a federal waiver await consideration, CSPR believes that special weight and consideration should be given to the system put in place by Rhode Island. The Global Consumer Choice Waiver is a comprehensive strategy with a demonstrable record of curbing cost while not harming the quality of care for patients.

Conclusion

Reforming Colorado’s Medicaid program will be no small endeavor. If state governments are to do more than simply tinker around the edges of this rapidly expanding program, the federal government will need to take steps to restore discretion to state policymakers so that they can narrowly tailor the program and benefit structures within certain parameters to meet the states unique needs.

There are several examples of lawmakers and governors in various states, from both political parties, working together to find opportunities to reform Medicaid to do just that. Much like the competing welfare reform concepts witnessed in various states during the mid-1990s, these reforms do not all look that same.

The approaches taken by other states are not necessarily the same path that should be followed by Colorado legislative leaders – but they should be considered. There are too many warning signs that strongly suggest the need for some sort of action to completely ignore Medicaid altogether. Indeed, true budget reform is simply impossible unless real and meaningful Medicaid reform is a part of the solution.

Appendices

Appendix A:

House Bill 05-1262 (Amendment 35 implementation)

How the new revenue was supposed to be appropriated:

- Increasing the number of pregnant women and children enrolled in the Children’s Basic Health Plan (CHP+) above the average enrollment for state fiscal year 2004.

- Add parents of enrolled children

- Expand eligibility of low-income adults and children who receive medical care through CHP+ or Medicaid.

In 2006, the General Assembly adopted House Bill 05-1262 to implement the provisions of Amendment 35. The bill made the following changes to Medicaid and CHP+ to comply with the requirements of Amendment 35:

- Increased CHP+ eligibility from 185 percent to 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

- Removed the requirement that children and families have minimal assets in order to qualify for Medicaid.

- Expanded the number of children that could be enrolled in the Children’s Home-and- Community based Service Waiver program and the Children’s Extensive Support Waiver Program.

- Increased Medicaid eligibility to 60 percent of the federal poverty level for a parent of a child who is eligible for Medicaid or CHP+

- Funded Medicaid for qualifying legal immigrants

- Paid for enrollment increases about the average enrollment for state FY 2003-2004 in the CHP+

- Provided $540,000 for marketing to increase the enrollment of eligible children and pregnant women in the CHP+

- Provided Presumptive eligibility to pregnant women under Medicaid

The bill also expanded the eligibility of individuals for the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment program from approximately 185 percent to 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Level.

Information source: Colorado Legislative Council Memo, Elizabeth Burger, “Medicaid Eligibility Increases and Caseload Expansions”, November 12, 2009.

Appendix B:

House Bill 09 – 1293 (Hospital Provider fee)

House Bill 1293 allows the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing to assess a fee against hospitals. The fee will be used to draw down additional federal funding to expand state health care programs and increase reimbursement payments to providers.

Assuming sufficient fees and federal funding are made available the bill would expand public health programs as follows:

- Increases the income eligibility limit for CHP + from 205 to 250 percent of the federal poverty level for both children and pregnant women.

- Increases the income eligibility limit for Medicaid for parents from 60 up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level.

- Provides for 12 month continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid.

- Creates a new Medicaid buy-in program for disabled adults and children with income up to 450 percent of the federal poverty level.

- Expands Medicaid to cover childless adults with incomes up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level.

Information source: Colorado Legislative Council Memo, Elizabeth Burger, “Medicaid Eligibility Increases and Caseload Expansions”, November 12, 2009.

Works Cited

1 Brown, Charles S., and Roberts, Jeffrey A. “Colorado Budget Tsunami,” University of Denver Center for Colorado’s Economic Future. June 2009.

2 Klemm, John D. “Medicaid Sending: A Brief History”. Health Care Financing Review. Fall 2000. Web. 19 September 2011.

3 Klemm, John D. “Medicaid Sending: A Brief History”. Health Care Financing Review. Fall 2000. Web. 19 September 2011.

4 Klemm, John D. “Medicaid Sending: A Brief History”. Health Care Financing Review. Fall 2000. Web. 19 September 2011.

5 Miller, Judith. “White House to seek budget cuts of $40 billion in 1982 fiscal year.” The New York Times, 6 February 1981. Web. 20 September 2011.

6 Provost, Christie. “Medicaid: 35 Years of Service.” Health Care Financing Review. Fall 2000.

7 Kaiser Family Foundation. “Medicaid: A timeline of Key Developments.” Web. 2 October 2011.

<http://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid_timeline.cfm>.

8 Congressional Record 1989. p. H5941. Available from: Thomas.loc.gov. Web. 7 September 2011.

9 Kaiser Family Foundation. “Medicaid: A timeline of Key Developments.” Web. 2 October 2011.

<http://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid_timeline.cfm>.

10 Davis, Patricia, Mitchell, Allison, and Fernandez, Bernadette. “Overview of Health Care Changes in the 2012 Budget Offered by House Budget Committee Chairman Ryan.” Congressional Research Service.

11 Luckie, Mark S. “A primer on Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security.” Washington Post Business. 4 May 2011. Web. 12 August 2011.

12 Herz, Elicia J. “Medicaid: A Primer.” Congressional Research Service. 11 January 2011.

13 Davis, Patricia, Mitchell, Allison, and Fernandez, Bernadette. “Overview of Health Care Changes in the 2012 Budget Offered by House Budget Committee Chairman Ryan.” Congressional Research Service.

14 Brown, Charles S., and Roberts, Jeffrey A. “Colorado Budget Tsunami,” University of Denver Center for Colorado’s Economic Future. June 2009.

15 Hoover, Tim. “Colorado scaling back Medicaid after drastically underestimating numbers, cost.” Denver Post. 31 August 2011. Web. 1 September 2011.

16 “Financing Colorado’s Future, An Analysis of the Fiscal Sustainability of State Government.” University of Denver Center for Colorado’s Economic Future. April 2011.

17 Haislmaier, Edmund. “Expanding Medicaid: The Real Cost to the States,” The Heritage Foundation. 14 January 2010.

18 Herrera, Christine. PPACA, Medicaid, and the States ALEC Presentation. 2 June 2011. Address.

19 “Financing Colorado’s Future, An Analysis of the Fiscal Sustainability of State Government.” University of Denver Center for Colorado’s Economic Future. April 2011.

20 National Governors Association and National Association of State Budget Officers. “The Fiscal Survey of States” Fall 2010.

21 Luhby, Tami. “States pour money into Medicaid.” CNN Money. 2 June 2011. Web. 25 July 2011.

22 Orszag, Peter. “A Health Care Plan for Colleges.” New York Times. 18 September 2010. Web. 25 July 2011.

23 Luhby, Tami. “States pour money into Medicaid.” CNN Money. 2 June 2011. Web.

24 “Financing Colorado’s Future, An Analysis of the Fiscal Sustainability of State Government.” University of Denver Center for Colorado’s Economic Future. April 2011.

25 Baird, Susan A. “R.I. unveils details of Medicaid ‘compact’.” Providence Business News. 23 December 2008. Web. 20 August 2011.

26 “Rhode Island’s Medicaid Lesion.” Wall Street Journal. 28 March 2011. Web. 20 August 2011.

27 Graham, John. “Washington‘s Medicaid reform could benefit every state in US.” The Examiner. 4 July 11. Web. 24 October 11.

28 “Quinn Signs Medicaid reform into Illinois law.” The Associated Press. 25 January 2011. Web. 5 September 2011.

29 Caputo, Marc. “Florida Medicaid reform embraces controversial push toward managed care”. St. Petersburg Times. 15 April 2011. Web. 24 October 2011.

30 Galewitz, Phil.”States turn to private insurance companies for managed care.” USA Today. 21 February 2011. Web. 27 July 2011.