Download a pdf of the full report >>

Download a pdf of key findings of the report >>

Download a pdf of a single page overview: A Health Care State Option for Colorado: What Does it Mean? >>

September 2019

Conducted by

ABOUT THE REMI PARTNERSHIP

A partnership of public and private organizations announced in July 2013 the formation of a collaboration to provide Colorado lawmakers, policymakers, business leaders, and citizens, with greater insight into the economic impact of public policy decisions that face the state and surrounding regions. The parties involved include the Colorado Association of REALTORS®, the Colorado Bankers Association, Colorado Concern, Common Sense Policy Roundtable, and Denver South Economic Development Partnership. This consortium meets monthly to discuss pressing economic issues impacting the state and to prioritize and manage its independent research efforts.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Colorado Governor Jared Polis and his policy advisers are contemplating a major new intervention in the state’s health insurance and health care markets. In partnership with legislative leaders, the Polis administration is developing a so-called state option: a new type of insurance plan that would significantly expand the role of state government within Colorado’s health care industry.

To date, a state option has never been fully implemented at a state or national level before and, under the current timeline, legislation to create a state option in Colorado could be introduced and passed early next year. In this report, the REMI Partnership explores the potential impacts of a state option to Colorado’s health care system and the broader economy. Given the potential impacts, the goal is to help policymakers and stakeholders make informed and timely decisions about recently passed legislation, HB19-1004, and the resulting pending proposal from the state.

Most concerned parties share an objective to make health care coverage more affordable, however, proposals to restructure the financing and delivery of health care, especially those which would expand public health coverage that does not pay for the full costs of care, should be carefully scrutinized. Although well-intentioned, such provisions may cause more harm than good.

After studying the potential impacts of the state option in Colorado, the results of economic modeling indicate;

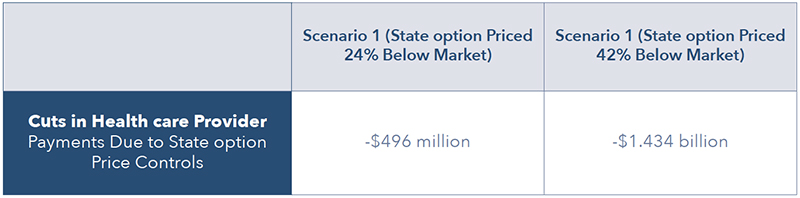

- Government price controls that are needed to facilitate below-market premiums offered by a state option likely do not cover the full costs of care, and therefore the reduced reimbursements to health care providers could range from $494 million up to $1.4 billion.

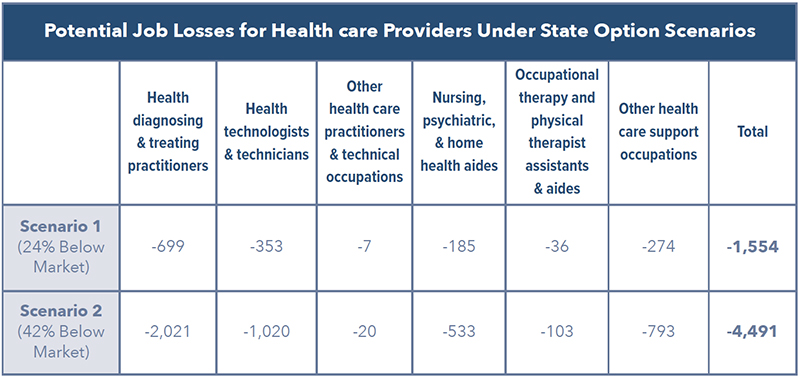

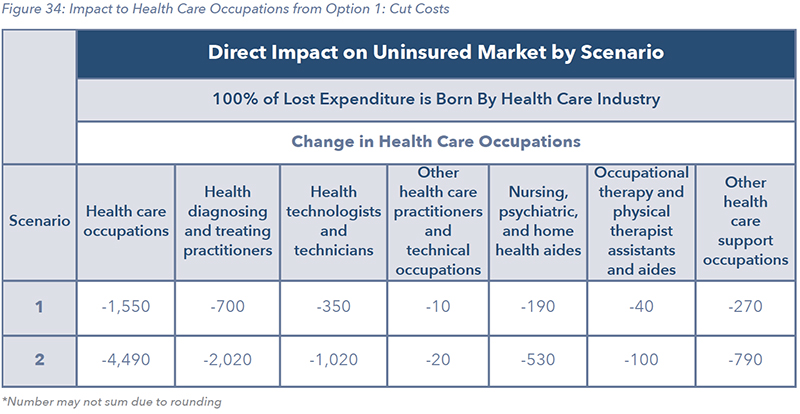

- The state option could cause a potential loss of 1,500 to 4,500 health care workers across Colorado, exacerbating the state’s existing shortage of primary care physicians, nurses, and other health care providers.

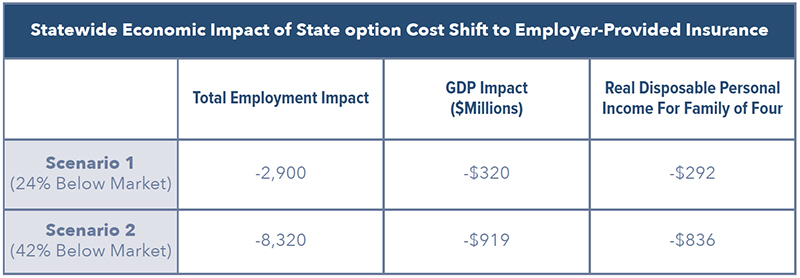

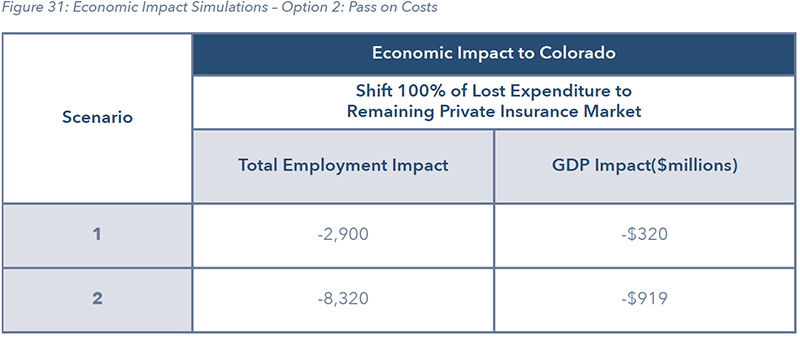

- If lost revenues from the state option are shifted to employer-provided insurance plans and other private sources, the state economy could lose between 2,900 and 8,320 jobs and $320 million to $919 million in total GDP, as a result of a more than 5% increase in the cost of health care for businesses.

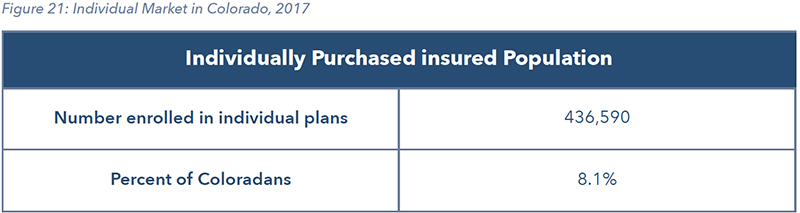

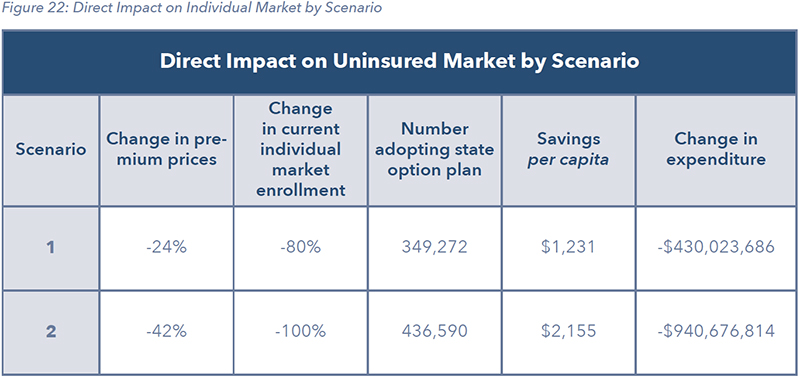

- An 80% to 100% membership loss could occur in the state’s individual health insurance market as people drop private coverage in favor of the state option’s below-market premiums.

- A reduction of 2.7% to 8.3% could occur in the employer-provided insurance market, which is the biggest source of health coverage for Coloradans in the state.

THE PROMISE AND THREAT OF A STATE OPTION

Calls to create state options are not unique to Colorado. Similar proposals have been introduced in Congress, promoted by presidential candidates on their campaign trails, and debated in other states this year. On the national stage, the leading state option proposal would create a new insurance plan called Medicare-X. In New Mexico, officials are studying a premium-based expansion of the state’s Medicaid program. In Washington state, a state option proposal called Cascade Care has been signed into law, and officials have planned a 2021 launch date for the new government-sponsored health insurance plan.

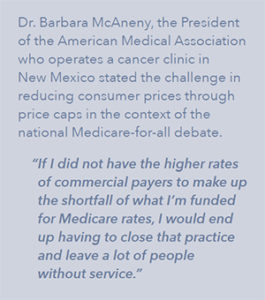

While details between different state option proposals may differ, they share a fundamental approach. Under a state option, officials create a government-sponsored insurance plan which offers significantly lower premiums compared to those being offered in the private insurance market. To support these below-market premiums, the state option laws require physicians, nurses, hospitals, and other health care providers treat patients with the new plan at reduced government rates, often proposed to be set at the same levels as Medicare or Medicaid, or at fixed percentages of those levels. A July 2019 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation stated “Mirroring proposals at the federal level, a number of states have proposed public plan options … To lower the premium of the public plan, payments to [health care] providers are limited”1.

These price controls are central to Colorado’s state option’s viability, but they have raised concerns from health care providers and other stakeholders about its potential impacts to access to care, quality of care, and the stability of the broader health insurance market.

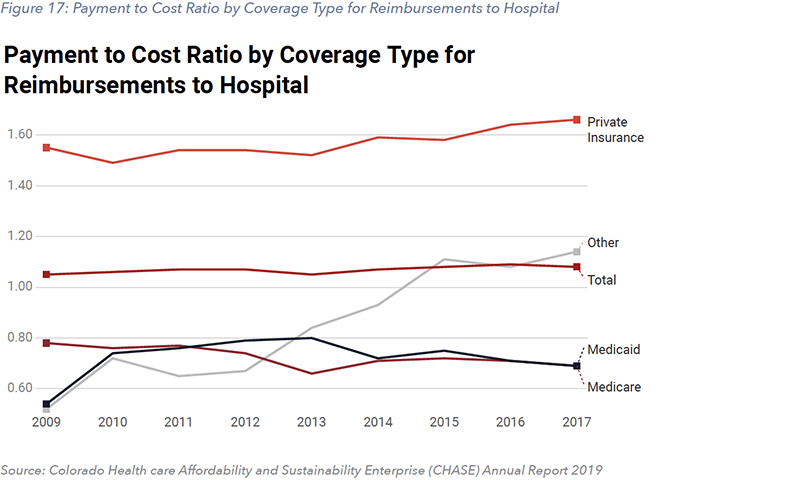

Medicare and Medicaid are social safety net programs which offer and provide health care coverage to senior citizens and low-income households, respectively. Historically, federal and state governments have set reimbursement rates for these programs well below the costs of providing the care they cover. For example, in Colorado, the Medicare payment-to-cost ratio for hospitals has ranged between 0.66 and 0.78 over the last decade. For Medicaid, the payment-to-cost ratio has ranged between 0.54 and 0.80 over the same period. According to the latest state data, the current payment-to-cost ratios for both Medicare and Medicaid in Colorado are now 0.69, meaning that Medicare and Medicaid payments for treatments cover only 69% of the costs of those treatments1.

Historically, to avoid cutting services, hospitals and other health care providers have relied upon higher payments from privately insured patients to recoup the unpaid costs for care from Medicare and Medicaid. If the state option expands similar price controls to a wider share of the health care sector by enrolling patients who are currently covered by private insurance, health care providers will find recovering their unpaid costs much more difficult.

For example, according to one recent study, a federal state option would place as many as 1,037 of the nation’s rural hospitals at a high risk of closure, “since they are thinly capitalized and have the smallest margin for error in their cash flows”3. This number equates to 55% of the nation’s rural critical access hospitals, according to the Navigant Consulting study, which was commissioned by a health care sector stakeholder group. The study also found that Colorado would experience closures in about 8 to 13 rural hospitals, depending on how many people drop their private health insurance in favor of the price-controlled state option.

Another recent study on the federal Medicare-X proposal, by KNG Health Consulting, found that a national state option would result in $774 billion in hospital reimbursement cuts over 10 years, a move that would “compound financial stresses already faced by the nation’s hospitals, potentially impacting access to care and provider quality”4.

The study, commissioned by two hospital sector professional associations, also found that 90% of enrollees in the state option would come from existing employer-provided or individual-market insurance plans, not the ranks of the uninsured. Furthermore, the Medicare-X option would increase the number of hospitals operating at negative margins and reinforce the existing losses to providers who administer care and treatment to Medicare patients below their actual costs. “Given that Medicare pays hospitals below their costs… Medicare-X Choice would be expected to increase the number of hospitals with negative margins,” the study found.

MODELED IMPACTS OF THE STATE OPTION IN COLORADO

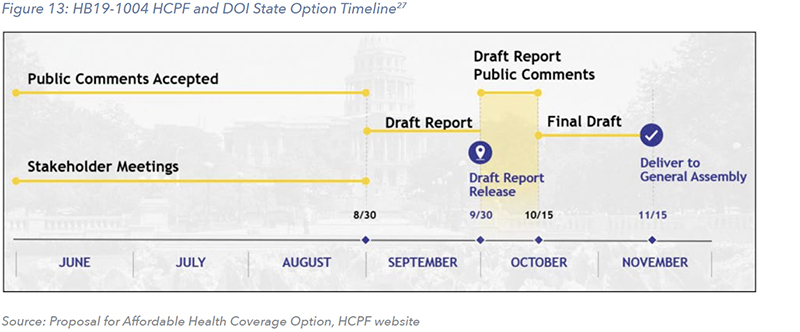

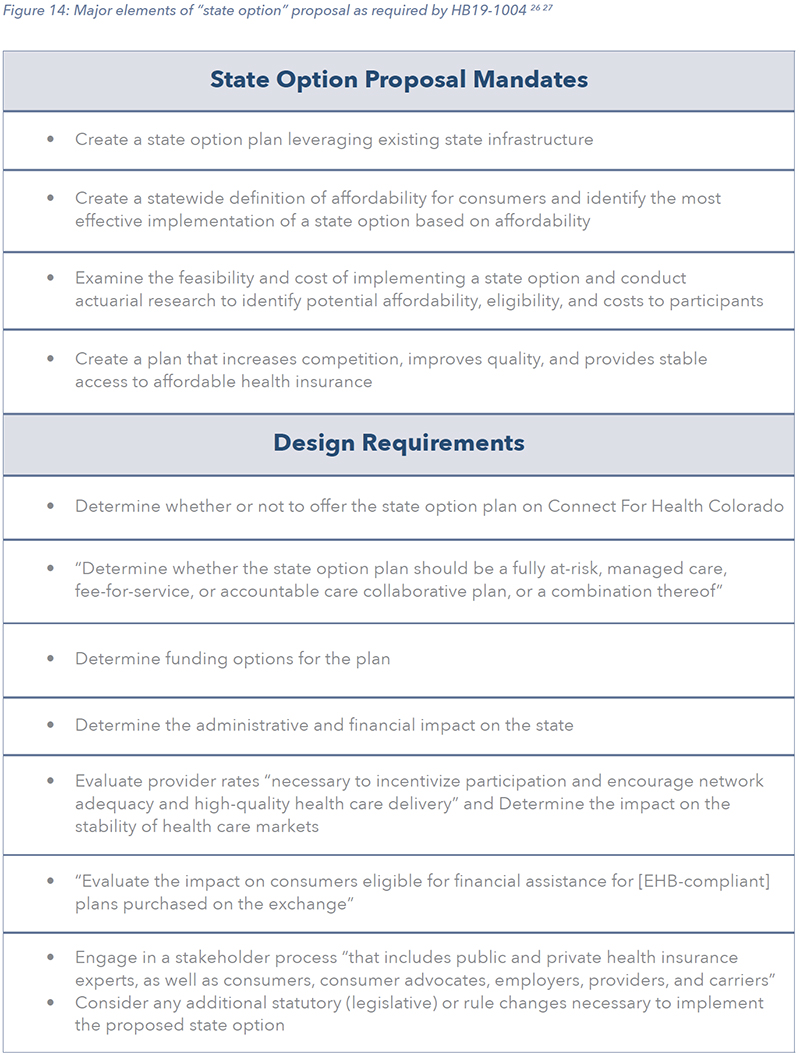

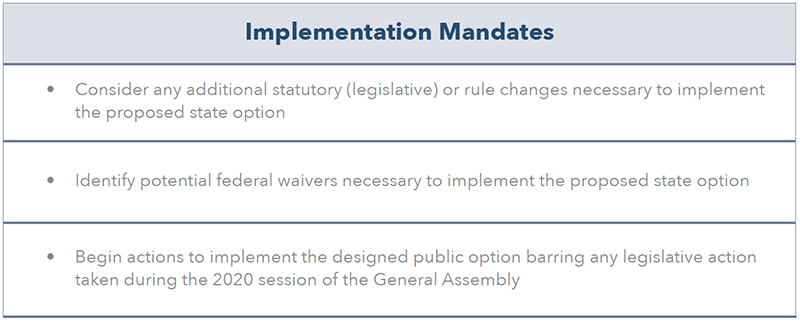

On April 22nd 2019, the Colorado legislature passed House Bill 19-1004. From the bill summary, HB19-1004 “requires the department of health care policy and financing and the division of insurance in the department of regulatory agencies (departments) to develop and submit a proposal (proposal) to certain committees of the general assembly concerning the design, costs, benefits, and implementation of a state option for health care coverage.” The deadline to submit a state option proposal to the state legislature is November 15th, two-and-a-half-months from the completion of several stakeholder meetings held across the state. According to the state’s Division of Insurance, this is “an incredibly short period of time” to create the new program5.

In light of the compressed timeframe, the REMI Partnership developed a series of state option scenarios for Colorado that drew on insights from the debate over HB 19-1004, and derived design elements from leading state option proposals, and their associated economic analyses.

The findings of this report are based on two potential scenarios. These scenarios mirror actuarial modeling done on an early version of Cascade Care in Washington state.

- Scenario 1: A statewide state option with premiums set 24% below market rates

- Scenario 2: A statewide state option with premiums set 42% below market rates

These scenarios are based on common design features from various federal and state public option proposals elsewhere, along with a range of premium reductions and price controls from Washington state’s original Cascade Care proposal. They are not intended to replace a complete actuarial analysis but intended to give the reader a sense of the direction and magnitude of the impacts and the various parts that could change under a state option. Under both scenarios, the introduction of a state option is highly disruptive to both the financing and delivery of health care in Colorado.

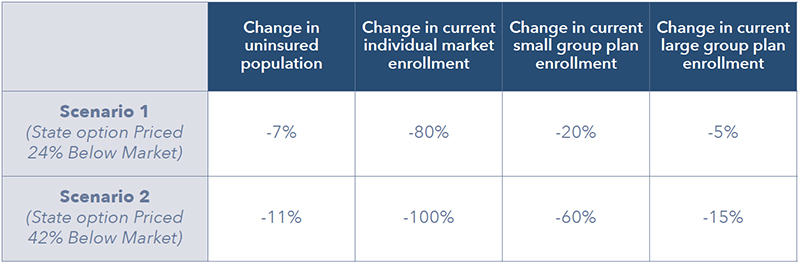

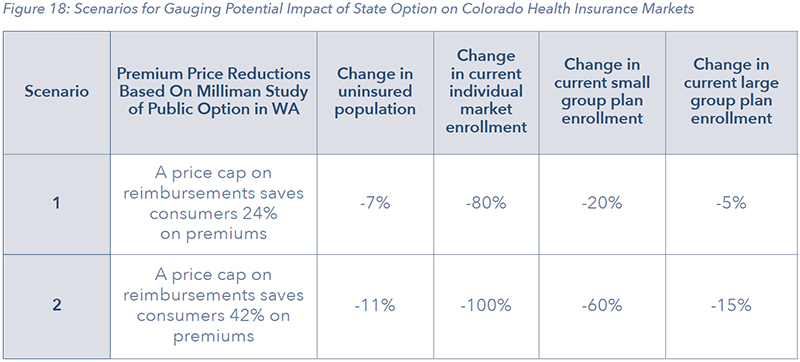

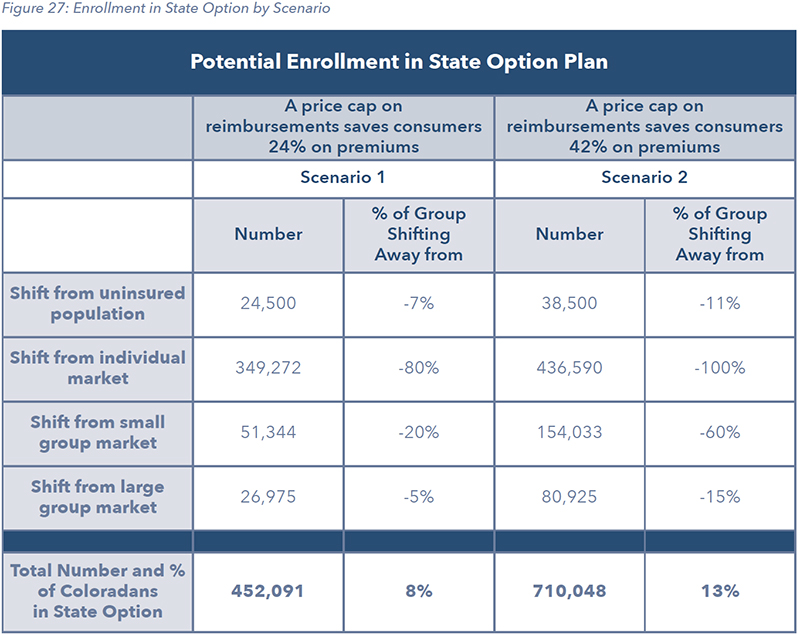

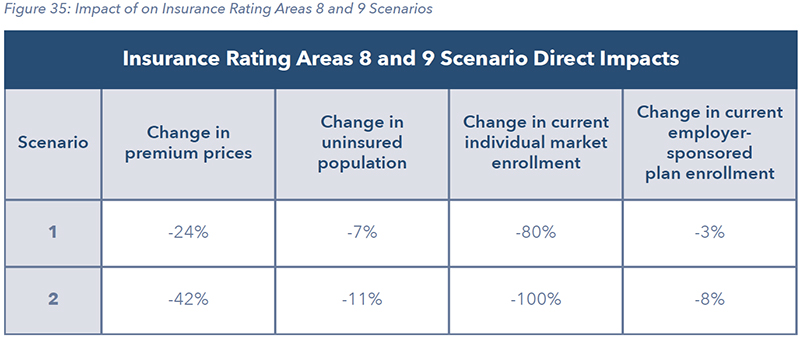

The subsidized premiums of the state option would prompt as much as 80% to 100% of participants in the state’s individual health insurance market to leave the private market altogether in favor of the new state-run plan. Moreover, even employer-provided insurance, primarily in small and large group markets, could lose current participants. While the scenarios in this report only suggested 2.7% to 8.3% of the 2.8 million-person employer insurance market would switch to a state option, estimates from the Navigant report include estimates up to 50% of employer markets. Below is a depiction of the direct impacts of the two scenarios analyzed in this report:

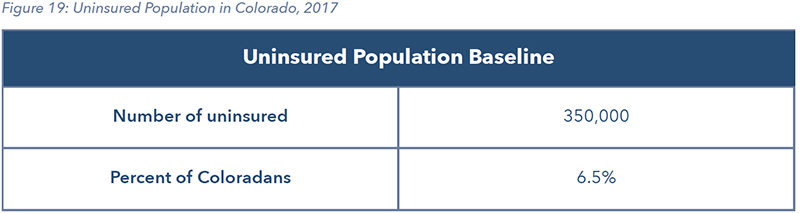

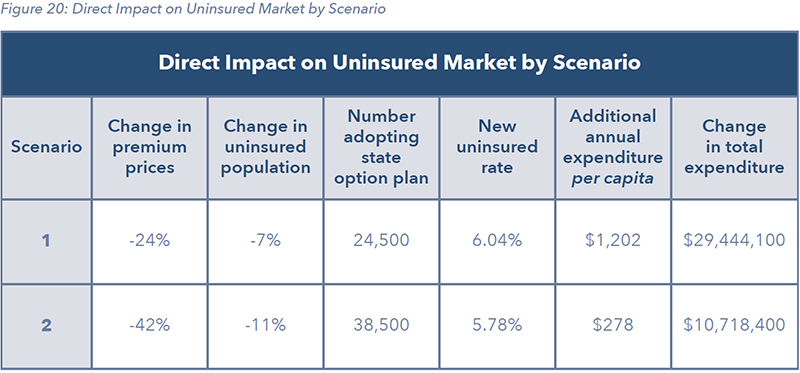

This represents a major contraction of the private health insurance market in Colorado, spurred by an expansion of government-provided coverage in the form of the state option. The shift in individuals from private insurance given the two scenarios ranges from 427,500 to 671,500 Coloradans. But in terms of expanding overall coverage, the benefit, a reduction in the state’s uninsured population of between 7% and 11%, a total of 24,500 to 38,500, is minimal.

Therefore, the state option’s largest impact appears to be moving people out of private insurance and into price-controlled, government health coverage.

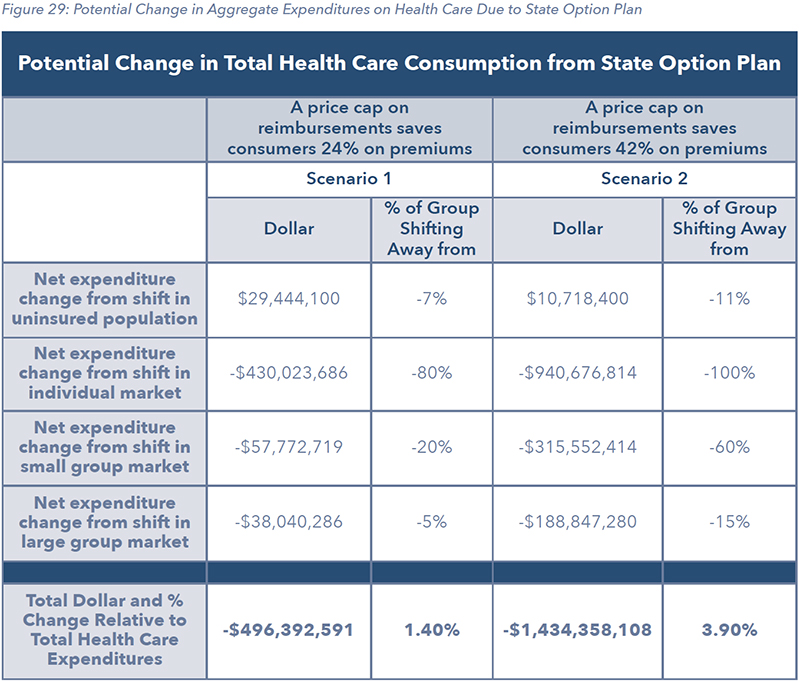

The impact of those price controls would be felt immediately by physicians, hospitals and other health care providers across the state, soon to be followed by patients and employers. Under both scenarios, payments to health care providers would be cut significantly and losses would range between $496 million and $1.4 billion per year.

If hospitals and other health care providers cannot recover these losses, it may lead to staffing reductions and some providers closing their doors, both of which have immediate impacts on access to care and the quality of care provided. Our analysis shows if these losses are completely borne by health care providers, it would result in the loss of between approximately 1,500 and 4,500 health care workers in Colorado. This includes doctors, nurses and others directly involved in patient care.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Colorado already faces a chronic shortage of health care providers. More than 1 million Coloradans live in a Health care Provider Shortage Area and correcting this shortage would require at least 264 new primary care physicians in the state6. The shortage of nurses is even more acute and measured in the hundreds7. These chronic shortages would be significantly worsened if thousands of health care workers lost their jobs because of a reduction in what providers are reimbursed for treating patients.

Given the severity of these impacts on health care providers, it is possible they will try to shift some of the unpaid costs of the state option to the private insurance market. Because of the severe erosion of the individual market, the employer-provided segment of the health insurance market would be the only place providers could turn to.

For this reason, we also modeled the broader economic impact of shifting $496 million to $1.4 billion of unpaid costs tied to the state option on the state’s employers and workers. The economic headwinds created by these additional business and employer costs are significant, potentially costing between 2,900 and 8,320 jobs and $320 million to $919 million in lost state gross domestic product (GDP). While the per capita income loss ranges from $73 to $209 dollars, for a family of four that would amount to between $292 and $836 per year.

CONCLUSION

Expanding health care coverage and access to affordable and high-quality care is a goal broadly shared across Colorado. However, as policymakers and stakeholders strive to reach that goal, there is a real danger well-intentioned proposals could cause more harm than good.

This is especially important to remember when debating health care policy in Colorado, because our state’s health care system is performing much better than many others across the country.

For example, Colorado has the fifth lowest health spending per capita in the nation8, despite our rising cost of living. In terms of quality, Colorado consistently ranks as one of the top states in the country and the state is a center of innovation and excellence, with several of the nation’s best hospitals located here9.

Colorado is not immune to national trends in health care, of course. Almost a decade of instability and regulatory uncertainty in health care markets has contributed to higher prices for health care coverage and health care services, especially for those who are privately insured.

But policymakers should think carefully before simply expanding the use of government price controls in Colorado’s health care sector via the state option. Legislating lower prices does not make costs disappear. Instead, it shifts those costs somewhere else, where they can cause major damage to our health care workforce, to the markets where most people obtain health care coverage, and to businesses and households across the economy. The damage may be unintended but that does not make the damage any less serious.

Therefore, policymakers involved in the design and review of the proposed state option may wish to ask themselves: After a decade of upheaval in national and state health care markets, is another major disruption what the Colorado health care sector needs right now? As was learned during the debate over this year’s reinsurance bill – HB 19-1168 – measures bring stability to the state’s health care market can deliver significant consumer savings, expand choice and promote competition in ways that benefit all stakeholders.

WHERE DOES COLORADO’S HEALTH CARE SYSTEM CURRENTLY STAND?

HEALTH CARE ECONOMY

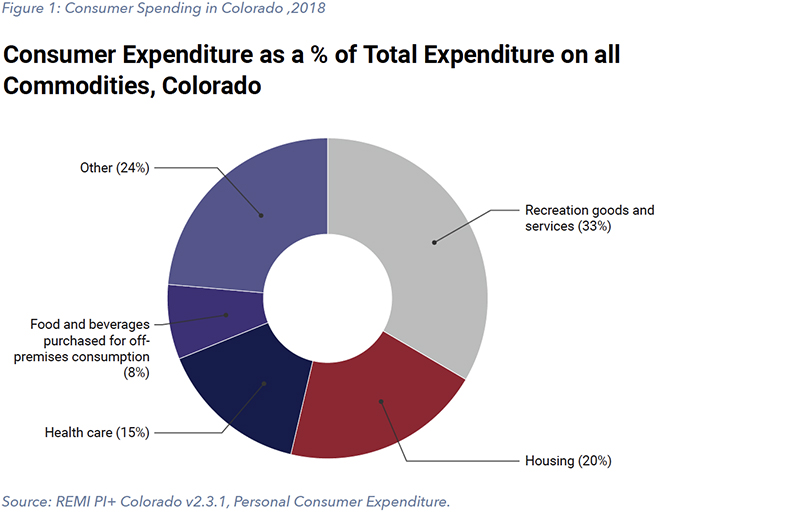

In 2017, Coloradans spent $6,500 on average on health care, totaling just over 15% of total personal consumption10. Accounting for consumer expenditures on out-of-state providers, the total combined contribution of all health care activities to state GDP in 2018 was $24.2 billion (6.3% of total GDP)11. The health care industry—ambulatory services, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities—provides nearly ten percent of Colorado’s jobs. In recent years, 34 cents of every dollar the state government has spent has gone toward covering the cost of care, primarily for those enrolled in Medicaid12. Whether it is viewed from a consumer, provider, or policymaker standpoint, health care is a substantial part of the Colorado economy and daily life.

Because of the significance of health care to both daily life and the economy, it is a constant subject of interest for policymakers, businesspeople, and patients. As such, it is worth assessing the standing of Colorado’s health care system. What does the market look like? Where is Colorado doing well? Where is the state lagging? These questions serve as the starting point to any reform conversation. To help answer them, several organizations have compiled insightful state rankings of health care quality holistically and by industry components.

HEALTH CARE OVERALL AND OUTCOMES

Several methods of evaluating a state’s health care system exist, but most rankings tend to consider price, expenditure, quality, outcome, and ease of access to providers. The reports listed below, in aggregate, indicate that Colorado ranks relatively high in health care quality and outcomes:

- The 2019 “Scorecard on State Health System Performance” published by the Commonwealth Fund ranks Colorado’s health care system 9th best nationally13.

- The U.S. News and World Report 2019 found that Colorado has the 12th best health care in the US; the state scored high marks for quality and public health indicators, its fewer-than-average uninsured adults and preventable hospital admissions, and its population’s low obesity rate14.

- Using a comprehensive ranking methodology incorporating behavior, clinical care, policy, community, and environment, United Health Foundation ranks Colorado as 8th best overall. It also ranks Colorado as 3rd best in the nation in-terms of outcomes, with particularly lower levels of diabetes, cardiovascular death, cancer deaths, frequent physical distress, and infant mortality15.

- As of 2017, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation ranked Colorado as the second most active state in the country, with over 84% of adults who are physically active.

- Similarly, the American College of Sports Medicine ranks the Denver metropolitan area as the 7th fittest in the country and awards it high scores in most physical activities and lower rates of obesity16.

While these studies suggest a relatively effective and successful health care system in Colorado, a closer look at these same rankings also indicates certain areas of concern. Despite depicting relatively better performance and outcomes overall, these rankings also suggest Colorado ranks relatively lower when it comes to categories of access, particularly outside of the state’s urban areas.

ACCESS

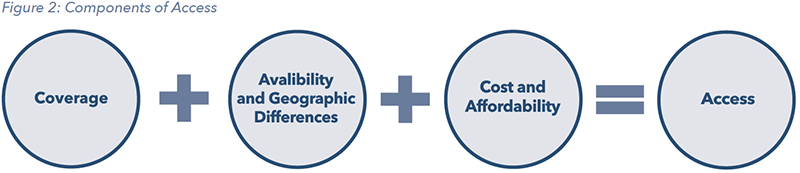

Generally, accessibility to health care is recognized by stakeholders and policymakers as an area for improvement, but its conceptualization is often glossed over. As the term “access” is complex, its definition varies across studies, and some exploration is required to both define access and understand how it varies across Colorado.

The RAND Corporation, a U.S. based think tank and global research organization, defines access as “the ease with which an individual can obtain needed medical services”17. Simply put, access entails all the factors influencing the utilization of health services ranging from the production to the consumption of such services. This necessitates looking at a bigger picture of accessibility, well beyond merely the procurement of health coverage. The Colorado Health Institute’s Health Access Survey, the most comprehensive assessment of issues surrounding “access” in Colorado, includes a wide array of access indicators such as health insurance coverage, barrier to care, reported perceptions of affordability, mental health and substance abuse rates and availability of associated services and use of health care, sliced by income, age, gender and counties within Colorado. This survey provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of access in Colorado and is drawn upon to support many of the inferences in this section18.

In keeping with the usefulness of a broader view of access, this report looks at three central elements. The first element is the nature and provision of health care coverage, by income and type of coverage. The second element is the availability, primarily through physical proximity, to a range of health care providers and services needed to improve and maintain health. The final element is the cost of those providers and whether an individual deems them to be affordable enough to utilize when needed.

HEALTH CARE COVERAGE

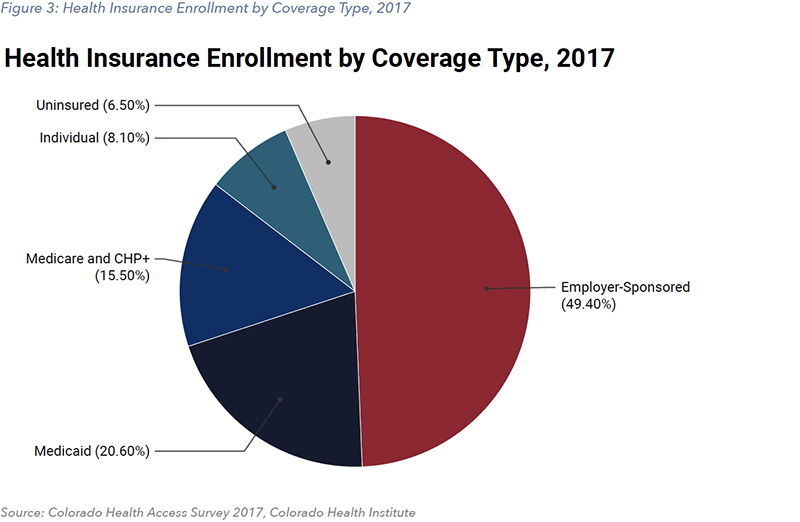

For various reasons, the current gateway to being able to afford care is almost exclusively through insurance. When the cost of health insurance increases relative to income, access also suffers as fewer people can afford or choose to purchase insurance. In 2017, 93.5% percent of Coloradans had health insurance coverage, either public or private, according to a survey by the Colorado Health Institute18.

According to the Colorado Health Institute’s 2017 Colorado Health Access Survey (CHAS) results, from 2013 to 2017, over 600,000 additional Coloradans obtained health insurance. This is primarily a result of the 2014 expansion of eligibility of Medicaid for individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level, and the creation of federal subsidies available to individuals making up to 400% of the federal poverty level following the changes of the Affordable Care Act. As of 2017, Colorado now has the lowest levels of uninsured in its history, at 6.5%, and has been consistently below the national rate since 2011 18.

As in all states, health coverage in Colorado is provided through a combination of public programs and private insurance carriers. The Division of Insurance (DOI) regulates commercial health carriers and Connect for Health Colorado, the state’s health insurance marketplace for individuals and small groups. The Department of Health Care and Policy Financing (HCPF) oversees the operations of Health First Colorado (Medicaid), among other public programs. Medicare is the federal government program to provide health care coverage for older Americans, primarily retirees. As of 2017, 58.1% of Coloradans had private insurance whether through an employer or through the individual market, and 35.4% had public insurance, primarily through Medicaid and Medicare.

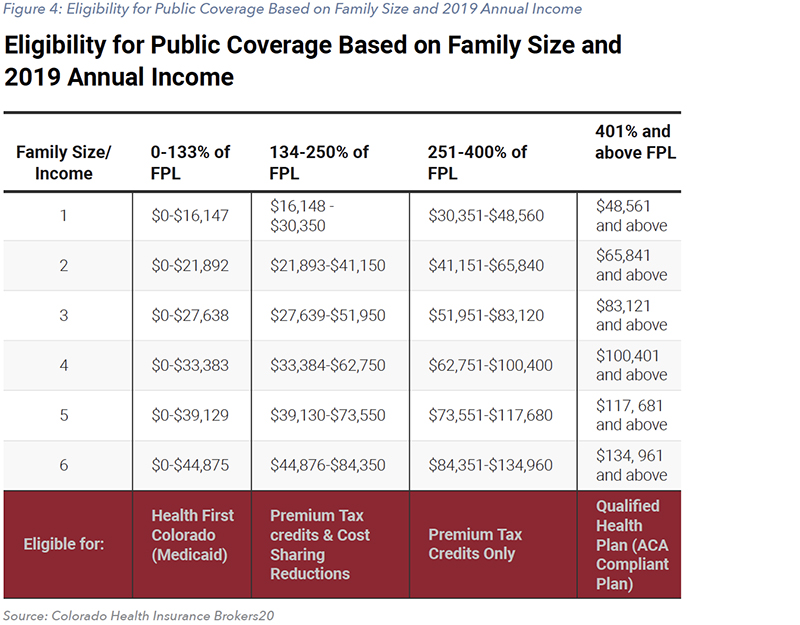

While eligibility for Medicare is based on age, eligibility for Medicaid is primarily based on income. For those who cannot enroll in either, federal subsidies are available to individuals or families with incomes up to 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL) who purchase insurance through the health care exchange. Eligibility for these public assistance programs and subsidies can be broken down by income level with respect to the federal poverty level and family size, as shown in Figure 4. This figure shows people in the lowest income range, officially between 0% and 133% of the FPL, are eligible for Medicaid through Health First Colorado19. The calculation adjustments eligibility for Medicaid is typically shown as available to people with incomes up to 138% of FPL.

Individuals or families earning 134-250% above the FPL are eligible for both Cost Sharing Reductions (CSR) which reduce deductibles and out of pocket expenses, as well as Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC) which cover some or all of the premiums. The APTC is specifically targeted at those who are neither eligible for Medicaid nor have access to employer-based health insurance plans. In Colorado, children under the age of 19 and pregnant women under 260% of FPL are also eligible to enroll in a Basic Health Program (BHP). Finally, those who earn 251-400% of FPL are only eligible for APTC, though under relatively more stringent rules, and those who earn 401% and are above the FPL are eligible for an Affordable Care Act-compliant plan known as a Qualified Health Plan20.

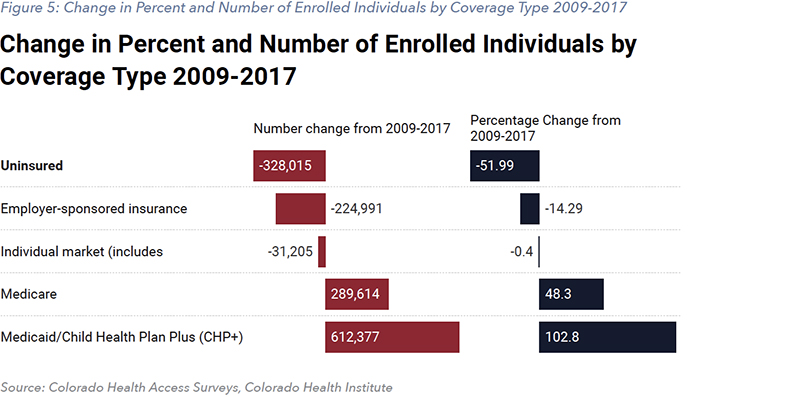

The CHAS depicts how the ACA and Medicaid expansion have altered the coverage scenario in Colorado over time. From 2009-2017, the rate of Medicare and Medicaid enrollments went up by 4.7% and 10.6%, respectively, while the uninsured rate went down by almost 7 percentage points. At the same time, the share of Coloradans covered by private insurance fell as the share of employer-sponsored coverage went down by 8.2 percentage points.

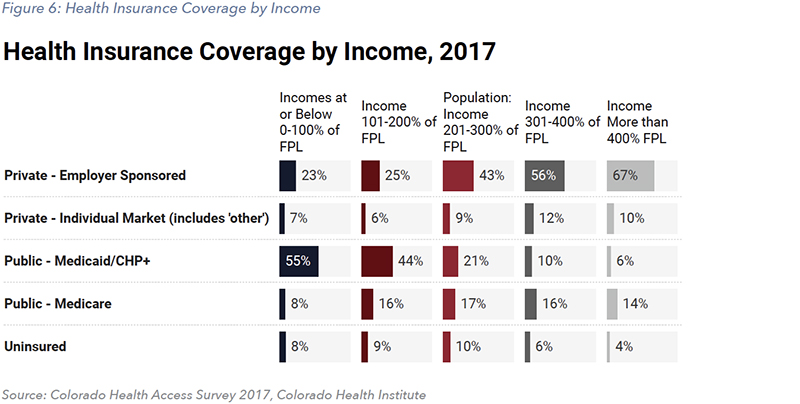

Income levels serve as another frame of reference for coverage differentials in Colorado. A Coloradan with earnings less than the federal poverty level was 26.3% more likely to be uninsured than another in any higher income bracket in 2009. However, as evident in Figure 6, in 2017, people earning between 200% and 300% of the poverty income level were the most (9.7%) likely to be uninsured. Therefore, while those at the higher end of the income spectrum are more likely to purchase private insurance, and those at the lower end of the income spectrum are more likely to be eligible for Medicaid or substantial subsidies, those in the middle-income ranges now have the higher rates of uninsured, as illustrated below18.

The number of people in Colorado who are uninsured dropped from 678,000 to 350,000 in the approximately 5 years leading up to 2017. Of those who are uninsured, CHAS shows that 23%, or 82,000 individuals, indicated they do not need insurance. Given this population is not eligible for Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, or other state or federal subsidies, it is likely that some are counted in the uninsured population.

The CHI’s Eligible But Not Enrolled Report presents an estimate for the status of the uninsured population as of 2016 21. This report estimates that 28% are currently eligible for Medicaid or CHP+, 29% are eligible for federal tax credits, 6% were offered affordable employer coverage, 25% were without documentation and 11% were above the federal poverty level.

This translates to just 47,000 Coloradans who were uninsured as they are not offered affordable coverage through work and don’t qualify for public coverage or federal subsidies as their income is over 400% of the federal poverty level. An additional 101,000 people are immigrants without documentation and not eligible for public coverage or federal tax credits.

When added up, 63% of the uninsured, or 258,500 people in 2016, were uninsured yet were eligible for public coverage through Medicaid or CHP+ but were not enrolled, were eligible for federal tax subsidies that reduce the cost of health insurance available on the exchange or had affordable coverage offered through an employer yet chose not to accept it.

REGIONAL ACCESSIBILITY AND SERVICE

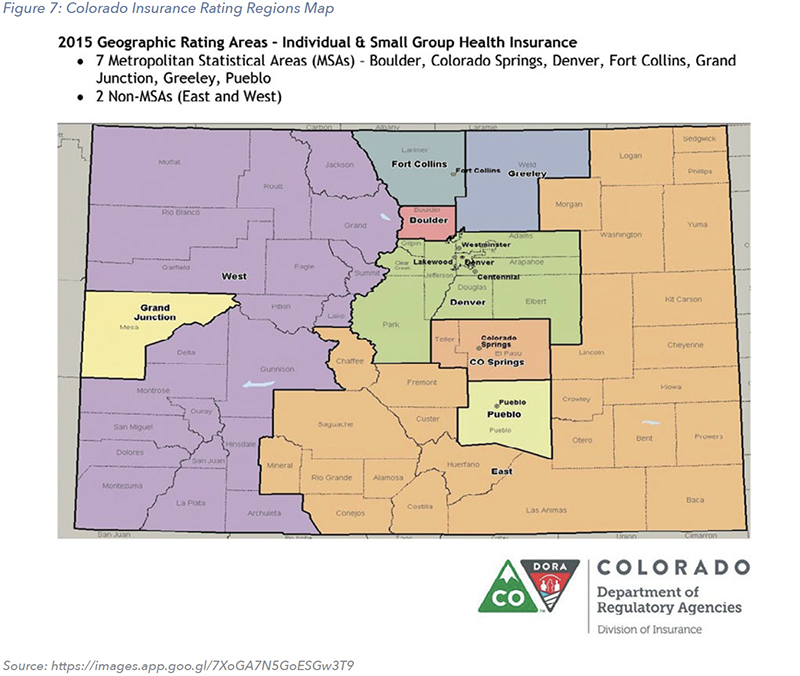

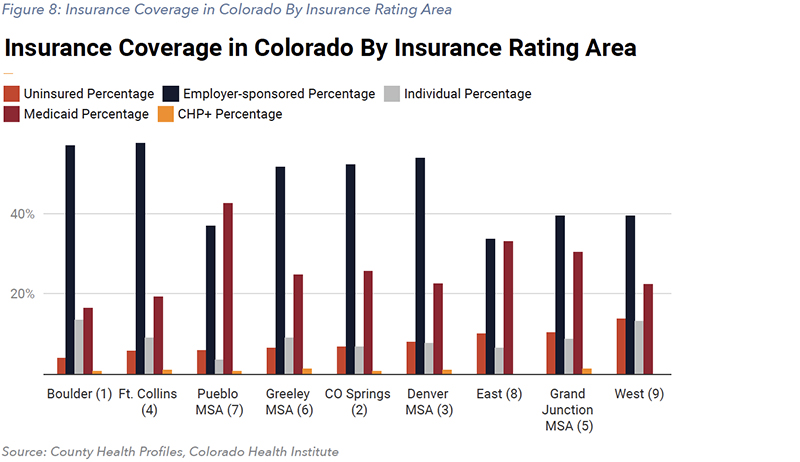

The second prominent component of accessibility in Colorado is regional or geographic differences in availability of health care services and types of coverage. Figure 7 shows the nine Geographic Rating Areas, as used by the Commissioner of Insurance to determine premium ranges. Within each region, the type of coverage varies. Figure 8 depicts the percentage of health insurance coverage within each insurance rating area.

The regional differences in access have major implications for whether people can afford to utilize the network of care that surrounds them. The greatest discrepancy in access can often be described between urban and more rural areas. The population density of urban areas leads to a higher concentration and quantity of demand for health care which can support a larger array of health providers ranging from primary care doctors to neurology specialists. Less densely populated communities do not have the same population density and therefore more often do not have the same array of providers within similar proximity.

Furthermore, providers and practitioners are neither adequately incentivized, nor motivated to serve patients under public assistance programs because of significantly lower reimbursement rates for services. According to the Colorado Rural Health Center, 73% of Colorado is considered rural or frontier, with 24 rural counties and 23 frontier counties. As of 2017, 13 of these counties do not have a hospital. The rate of uninsured as a share of population is about 6% higher for rural counties than urban or metropolitan areas, and 40% of Coloradans over 80 years of age live in rural areas.

Although health care is one of the top three industries in rural countries, 12 counties do not have behavioral (mental) health providers, 8 do not have a dentist and 2 do not have a physician22. Furthermore, the Colorado Health Institute reports the median wait time for specialty care can vary from 6.5 days in places like Douglas County, all the way up to 13.2 days in some of the rural or frontier counties23. While the share of enrollment in public insurance programs is higher in rural counties than urban, 52% of the rural population are on private plans.

However, 14 rural counties have only one private health insurance carrier, and these counties feature some of the highest premium rates in the state. Furthermore, the Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) has looked at commercial insurance plans and claims and reports substantial regional price variations across different health services for those on private plans. For example, a gall bladder surgery can cost $16,270 in Greeley but only $6,630 in Boulder, and a knee replacement and revision and revision can cost $58,750 in Fort Collins and $28,750 in Boulder for commercial insurers24. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), out of the 48 counties in Colorado that are designated as a medically underserved area, 33 (or 69%) of them are rural or partially rural and only 15 (31%) are non-rural.

Therefore, it is evident various factors such as considerable differentials in the provision, availability, prices, and user characteristics drive the geographic inaccessibility in Colorado. This is an important issue to consider for policymakers because it hampers even those with adequate coverage from attaining the health care services that they need due to geographic limitations.

COST AND AFFORDABILITY

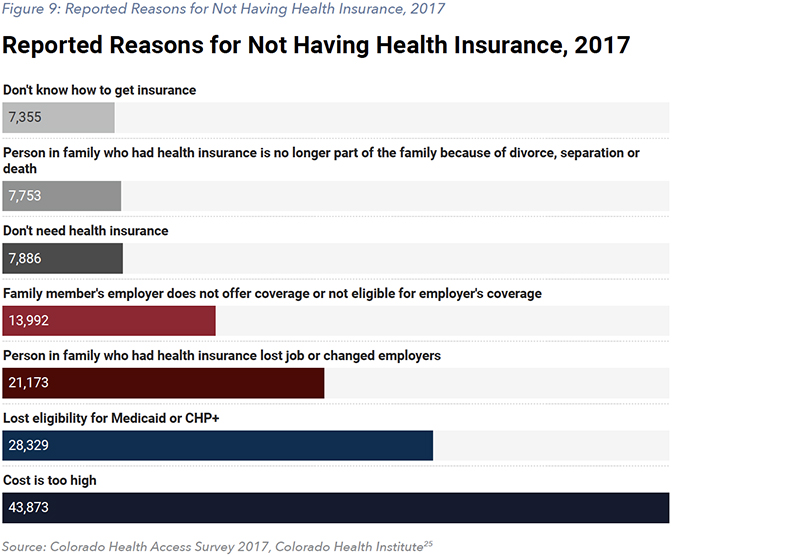

The Affordable Care Act effectively expanded insurance coverage through increasing eligibility for Medicaid and providing premium tax credits, causing the uninsured rate to drop from 13.5% in 2009 to 6.5% in 2017 according to the CHAS published that year. However, the costs of health care in the United States have continued to rise dramatically, albeit mostly to a lesser extent in Colorado15. Coloradans have continued to see their health care costs outpace their incomes, affecting affordability. Of the uninsured individuals interviewed in the CHAS survey, 78.4% reported not having insurance due to the cost.

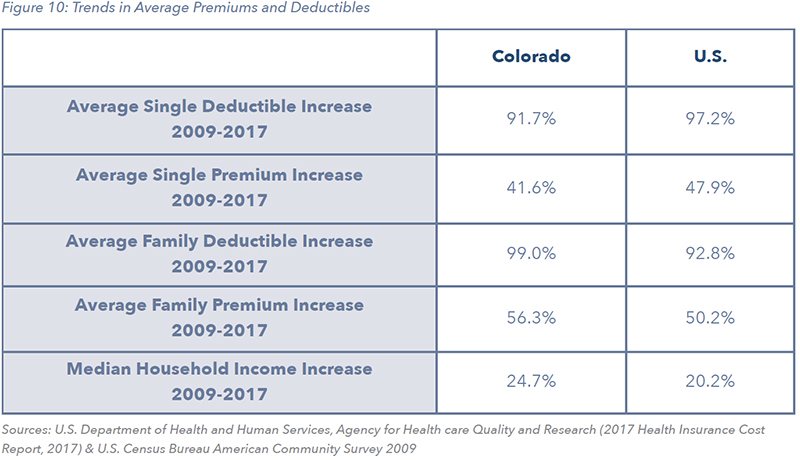

To control premium costs, insurers have trended toward increasing cost sharing for consumers, though this has not provided relief for many Coloradans. Figure 10 illustrates the average increase in premiums in deductibles from 2009 to 2017 when compared to the rest of the country. It is evident that increases in both single and family deductibles have outpaced income growth for most households.

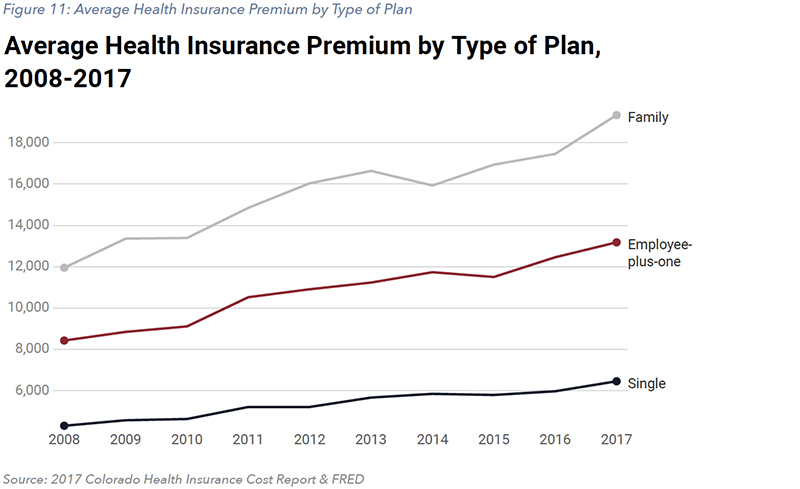

To further understand this dynamic, it is helpful to get insights on a specific type of coverage. The most prevalent source of coverage in the state is employer-based, which includes single, employee-plus-one, and family options. Figure 11 shows that the premiums have risen consistently for all three options over the last decade leading up to 2017.

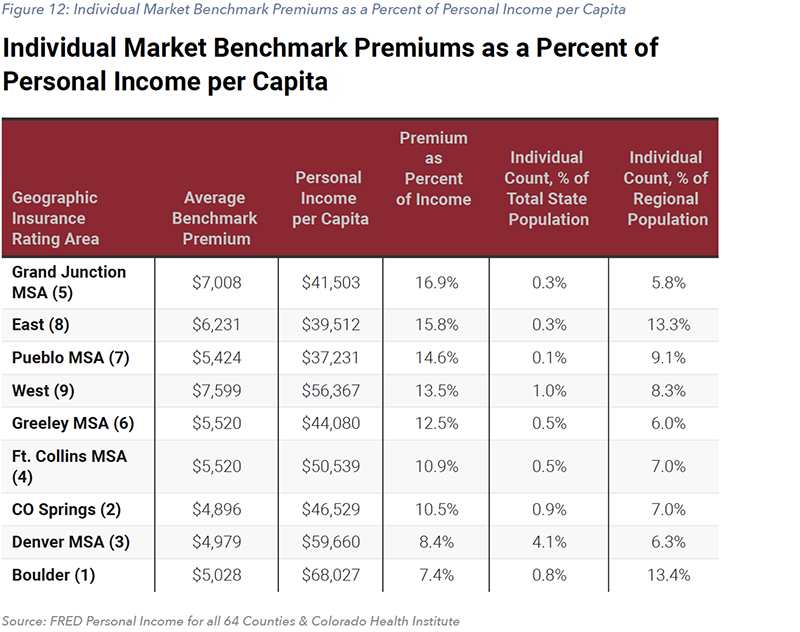

Furthermore, for those insured under the individual market, Figure 12 shows the premium of the benchmark plan sold across the nine insurance rating regions, relative to per capita income. By this measure, the cost of premiums relative to average income ranges from 7.39% to 16.89% across the different regions of Colorado. With additional data, it would be possible to report this affordability table by different types of insurance plans, particularly for older Coloradans or families. The ability to use premiums as a percent of income to represent the cost of care is limited as the true cost of care is often masked by federal subsidies given to consumers to offset costs. As such, Figure 12 is only one measure of affordability but offers a better view of the differences across the state.

The existing dynamics and trends within the health care market both nationally and in Colorado are complex. While the uninsured rate remains around 6.5%, the expansion of eligibility to Medicaid was the primary driver of nearly 7 percentage point drop in the overall rate. The cost of health care insurance in Colorado is rising, in line with national trends, but as a share of median income, health insurance is more affordable for most Colorado households than in other states. Any further policy action should clearly articulate what remaining challenges it is aiming to help resolve.

NEW COLORADO LAW: PROPOSAL FOR AFFORDABLE HEALTH COVERAGE OPTION

HB19-1004 SCOPE AND MANDATE

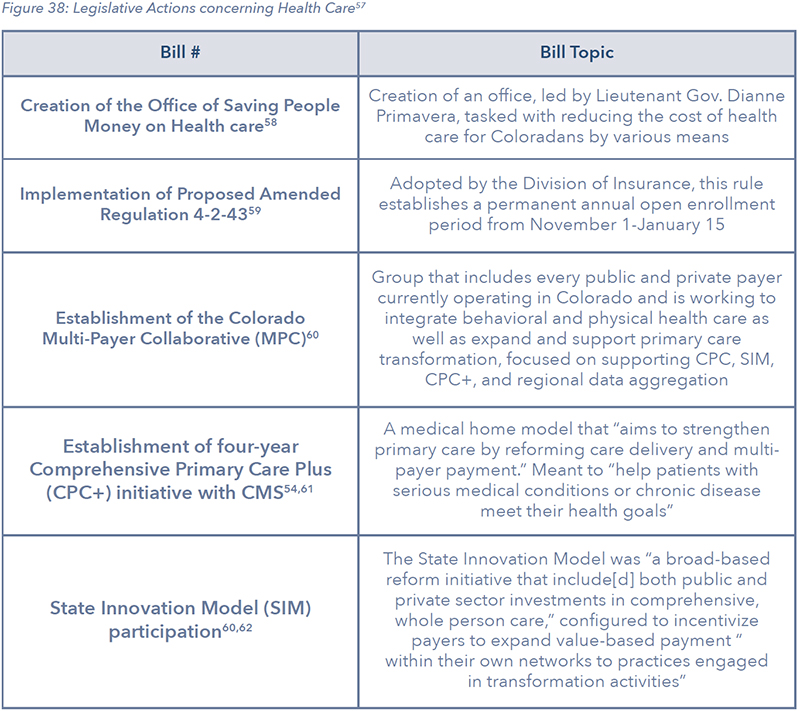

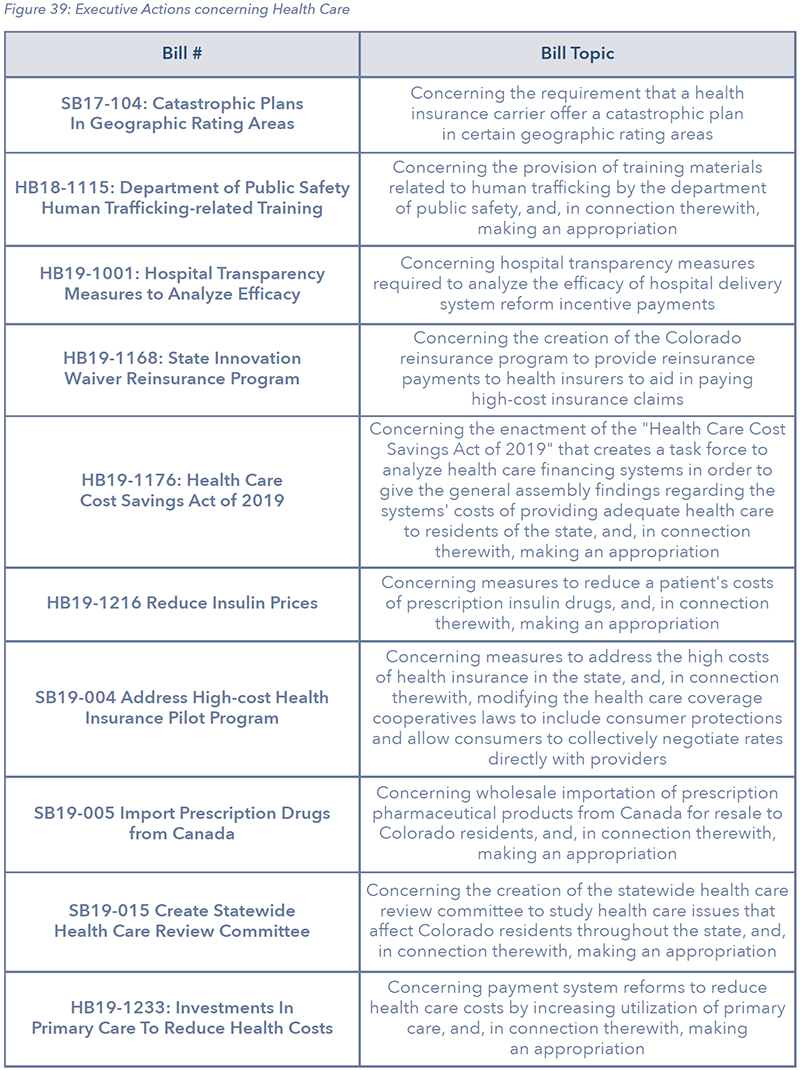

Several bills passed during the 2019 legislative session of the Colorado General Assembly were designed to address health care costs and inefficiency. Among these was HB19-1004, sponsored by Sen. Kerry Donovan and Reps. Dylan Roberts and Marc Catlin.

The bill, officially titled Proposal For Affordable Health Coverage Option, “requires the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF) and the Division of Insurance (DOI) in the Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) to develop and submit a proposal for a state option for health care coverage that leverages existing state health care infrastructure while also considering feasibility and cost”26.

Following a draft in September and a comment period the first two weeks of October, the final plan design is due on November 15. Section 7 of the law gives some authority to HCPF and DOI to take the necessary steps in applying for federal waivers and promulgating rules necessary to implement the proposed plan without further action by the state legislature.

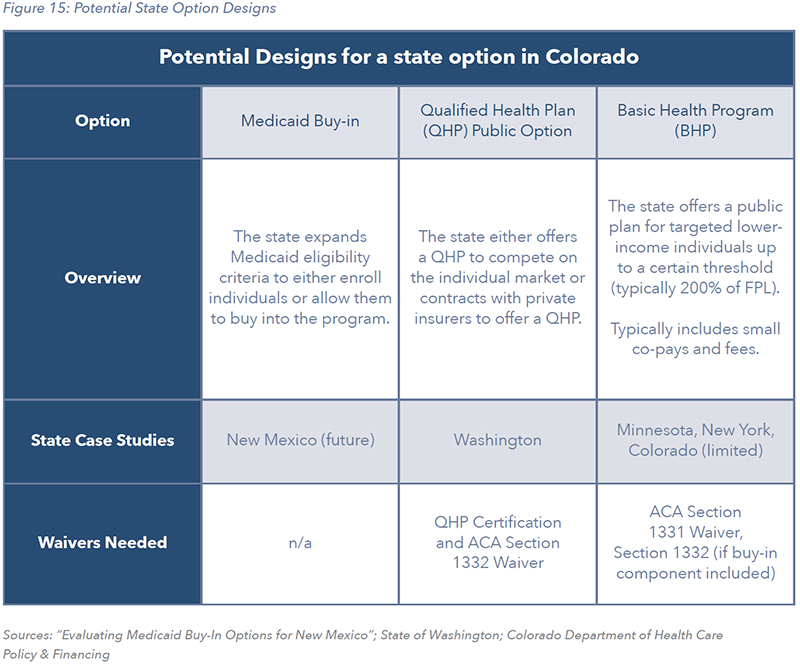

WHAT COULD A STATE OPTION LOOK LIKE? LESSONS FROM OTHER STATES

The final form a “state option” in Colorado will take has not been publicly announced. While a number of states have taken steps toward the creation of new public health coverage plans, only Washington state has passed legislation to begin creating a state option, which is called a public option in the state’s legislation. Several other states, namely New Mexico, have attempted or are still in the process of attempting to pass legislation to formally implement a public option. The Department of Health Care Policy & Financing (HCPF) has met with diverse groups of stakeholders to discuss the state option plan but has not provided any additional insight into the preferred path forward for a plan design.

After commissioning a two-phase study on a public option, New Mexico has deliberated the implementation of some form of an expansion of Medicaid through a targeted buy-in as recommended by the study. Meanwhile, the state of Washington created a more heavily regulated structure in which the state will contract with private insurers to offer state-sanctioned plans on the individual market. During the first stakeholder meeting about a state option, HCPF described the reforms enacted by Cascade Care as having “some promise across the board, particularly in Colorado”5. Finally, the states of Minnesota and New York have implemented what is known as a Basic Health Program for low-income individuals, though these plans may face funding challenges in the future.

MEDICAID BUY-IN: NEW MEXICO

Medicaid covers over 40% of the state’s population (in contrast to Colorado’s 21%), making it the state’s largest payer of health care expenses and making New Mexico the state with the highest percentage of residents on Medicaid. As such, the state wants to leverage its Medicaid provider network to lower costs. The state is considering a Medicaid buy-in option in response to a stubbornly high uninsured rate of over 9%, which has left some individuals paying over $800 in monthly premiums28.

In 2018, the New Mexico legislature passed Senate Memorial 3 and House Memorial 9, directing the Legislative Health and Human Services Committee to explore “the policy and fiscal implications of offering a Medicaid buy-in coverage option”29. Exploring the implications occurred across a two-phase study. Phase 1 provided “a qualitative assessment of several Medicaid buy-in options for New Mexico,” and Phase 2 conducted an actuarial assessment of a targeted buy-in29 30.

After the conclusion of Phase 2 of the actuarial study in early 2019, Manatt recommended that the state of New Mexico move forward in offering a targeted Medicaid-buy in30. Individuals who do not have access to other subsidized coverage due to income, immigration status, or the “family glitch” would be eligible for coverage under the targeted Medicaid buy-in plan. This plan includes premiums and cost-sharing, though the state is exploring ways to offset the cost of coverage. With some exceptions, the plan would emulate the state’s Medicaid benefit package. The administration of Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has taken steps to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates31, potentially to offset anticipated provider revenue losses from accepting more Medicaid patients.

QHP PUBLIC OPTION: WASHINGTON STATE “CASCADE CARE”

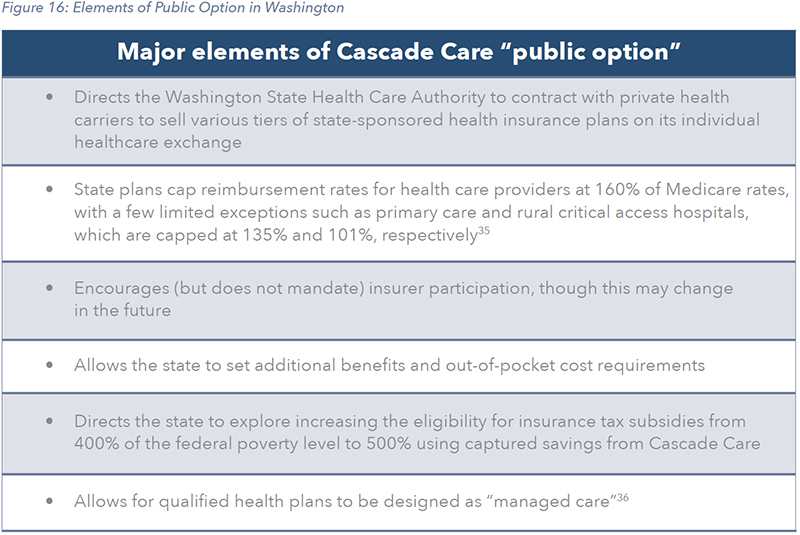

In May 2019, the Washington State Legislature passed Senate Bill 552632, creating a “public option” for health care insurance coverage known as Cascade Care. Beginning in the fall of 2020, private insurers will contract with the state to offer a “public option” plan through the existing individual market exchange33.

Cascade Care plans are more regulated than standard plans, most notably featuring caps on provider reimbursement rates set to a percentage of Medicare. Administration officials believe that successful implementation of the plan could reduce premiums for policyholders on the individual market by 5% to 10%. Senior staff to Washington Gov. Jay Inslee stated a belief that the largest beneficiaries of Cascade Care may be individuals in rural areas served by critical access hospitals34.

BASIC HEALTH PROGRAM: MINNESOTA, NEW YORK, COLORADO (LIMITED)

In various stakeholder meetings for a public option, HCPF has emphasized a desire to reduce “churn,” which occurs when “individuals or families may move into and out of different types of coverage or become eligible or lose eligibility for subsidies”37 based on fluctuating eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP due to income levels. Churn can be “very disruptive, sometimes forcing people to change their doctors or other health care providers, to possibly pay more or less in premiums and cost-sharing”37.

To better understand this phenomenon, HCPF has commissioned a churn analysis, as well as research and analysis of the “cliff effect” where individual incomes fluctuate above and below eligibility levels for these programs38. The results of these analyses have yet to be published. Beyond reinsurance, reducing churn is one method states have looked to in order to reduce risk for insurers and drive down costs39.

One possible method of reducing churn is the establishment of a Basic Health Program (BHP). Basic Health Programs can be established using a Section 1331 Affordable Care Act (ACA) waiver and can be funded using up to 95% of the state’s Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC)37 40. “BHPs aim to provide even cheaper coverage through significantly lower premiums and cost-sharing” to eligible individuals who are able but cost-burdened to obtain affordable insurance through the Health Insurance Marketplace41.

Colorado currently operates a limited Basic Health Program, known as CHP+, designed for children under the age of 18 and pregnant women over 19 who are lawful Colorado residents. CHP+ is “for people who earn too much to qualify for Health First Colorado (Medicaid), but not enough to pay for private health insurance” and covers applicants with household income from 133-260%, as opposed to the standard 200% of the FPL42. This program includes small co-pay for some services and annual enrollment fees43. If the state wished to expand its BHP as a public option buy-in program beyond the current served population, it may require an additional Section 1332 waiver29.

New York and Minnesota implemented broader Basic Health Programs in 2015, but changes at the federal level have threatened the viability of funding for these plans. These states stand to lose $300 million in federal funding over two years due to federal rule changes. As a result, these states may have to fund the shortfall from their own coffers44.

The Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing has emphasized the importance of funding sustainability in a state option, drawing lessons from previous risk-bearing enterprises such as the failed health insurance co-ops45. Unlike in New York and Minnesota, if new state funding was required in Colorado and adequate funding was not available through the general fund, then raising revenue via taxes would require a vote of the people.

CAPPING PRICES VS REDUCING COSTS

UNDERSTANDING PROVIDER REIMBURSEMENT RATES

Health insurance is the primary tool by which consumers pay for their health services. This is largely due to the uncertainty inherent in personal health. Health insurance works by pooling payments from many people who pay relatively small fixed amounts in the form of monthly premiums that then cover the costs of the payers’ claims when they utilize health care services. This typically means that, over any given time period, only a small proportion of people demand more in coverage than they pay into their respective insurance pools.

Insurance companies are responsible for paying health care providers, such as dentists or hospitals, for items that their customers’ insurance plans cover. Insurance carriers negotiate with health care providers to establish the prices that they pay for different procedures and products. This is where the battle over health care costs is fought, the outcome of which directly impacts customers.

WHO WILL BEAR THE COST OF A STATE OPTION?

The exact impacts of a state option on health care markets and Colorado’s economy will depend upon the ultimate proposal design. Though, as many industry insiders and public commenters have worried, the requirements of the plan outlined in the new law indicate a clear risk of potential adverse consequences.

There is an underlying dynamic to the health care market that is unique when compared to many other sectors. Through Medicare and Medicaid, both the federal and state governments act as purchasers of health care in a similar way to private insurance. While the exact figures may vary across sources and databases, Medicare and Medicaid often do not pay for the full cost of the care of the individuals they are covering.

According to the Colorado Health care Affordability and Sustainability Enterprise (CHASE) 2018 Annual Report, in 2017, the total of Medicare and Medicaid payments to hospitals was just 69% of the average expenses attributed to those patients. At the same time, the total of private insurance payments relative to average expenses was 166%. These figures are also referred to as the payment-to-cost ratios. While this methodology seemingly over-simplifies the ratio and does not provide a regional or hospital specific view, it does capture the overall trend existing within our health care markets. The annual data on the payment-to-cost ratios in Colorado are depicted in Figure 17.

According to the Colorado Health care Affordability and Sustainability Enterprise (CHASE) 2018 Annual Report, in 2017, the total of Medicare and Medicaid payments to hospitals was just 69% of the average expenses attributed to those patients. At the same time, the total of private insurance payments relative to average expenses was 166%. These figures are also referred to as the payment-to-cost ratios. While this methodology seemingly over-simplifies the ratio and does not provide a regional or hospital specific view, it does capture the overall trend existing within our health care markets. The annual data on the payment-to-cost ratios in Colorado are depicted in Figure 17.

A frequently discussed mechanism for easing insurance prices proposed as part of each state’s debate around a state option is the capping of reimbursement at a fixed amount relative to Medicare or Medicaid. Capping reimbursement costs without addressing underlying cost drivers of insurance plans or costs borne by providers is problematic. As shown above, in Figure 17, health providers already recoup the low prices of government insurance with private insurance. Further reductions in provider revenue without ways to reduce underlying costs will force providers to make decisions that could adversely impact quality and availability of care.

The first legislative declaration of HB-1004 reads, “Every Coloradan deserves access to high-quality, affordable health care to help support his or her well-being and economic security.” A state option offering substantially lower reimbursement rates, promises to deliver reduced insurance rates for consumers, at the same time it pays providers much less for the same services. Therefore, as the rate of uninsured may decrease, it comes at the expense of other components of access such as availability of quality and timely care.

MODELING THE TRADEOFFS OF A STATE OPTION

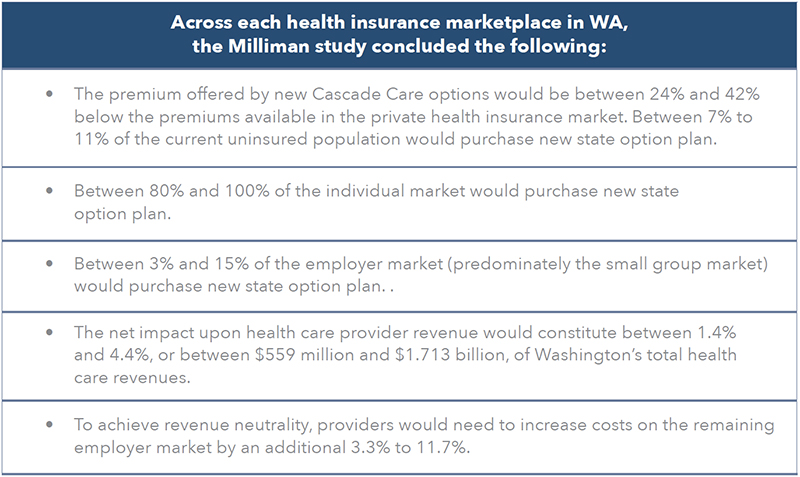

Prior to the development of the final plan design of Cascade Care, the Association of Washington Health Plans commissioned Milliman, a national leader in health care analysis, to conduct an actuarial analysis of the program’s potential impacts across different health insurance markets46.

The study paints an interesting picture as to what the likely impacts of a state option would be, as it clearly demonstrates the potential unintended consequences. The study was developed on an earlier version of Cascade Care than was ultimately enacted, at a stage where reimbursement rates were proposed to be set equal to Medicare. While in the final bill reimbursement rates were actually set at 160% of Medicare, useful insights can still be gleaned from the old findings given the proposed design in Colorado is currently unknown.

The study suggests there are different reimbursement rates paid by existing private insurers on the individual market, ranging from 140% of Medicare in low-cost areas to 190% in high-cost areas. This means the ultimate state option payments would fall in-between the reimbursement rates in the high-cost areas and those in the low-cost areas as estimated in the Milliman study.

As such, the publicly cited expected consumer savings to come as a result of the final version of Cascade Care are between 5% to 10%. Even if it were to cause a 24% to 42% reduction in the cost of insurance, as the Milliman study about the earlier draft of the bill suggested, only 7% to 11% of the existing uninsured population would opt to buy state plans. This means the actual impact upon the number of uninsured individuals under implementation of the final version of Cascade Care will likely be much lower.

The final draft of Cascade Care, though reduced in scope and impact compared to earlier ones, still forces an underlying trade-off to occur. Whereas lower priced insurance will attract some previously uninsured individuals, it will also entice many who are insured privately. The reimbursement rate for a state option plan relative to Medicare will dictate how disruptive the state option is to existing markets; if the reimbursement rate is low enough, a state option could devastate individual and employer-sponsored insurance markets.

To better understand these trade-offs in Colorado’s proposed state option, the REMI Partnership developed the following scenarios, modeled after the Milliman study, which outline the possible impacts across insurance markets.

POTENTIAL IMPACT OF STATE OPTION SCENARIOS

The following scenarios represent potential outcomes of the final design of a state option. It is clearly possible that what is developed by HCPF and DOI falls far outside of what has been discussed in this report and avoids the disruptions to existing markets in a way that is discussed here. These scenarios were created strictly for the purpose of understanding the trade-offs, the market dynamics, possible medical revenue changes, and potential broader impacts of price caps on the Colorado economy.

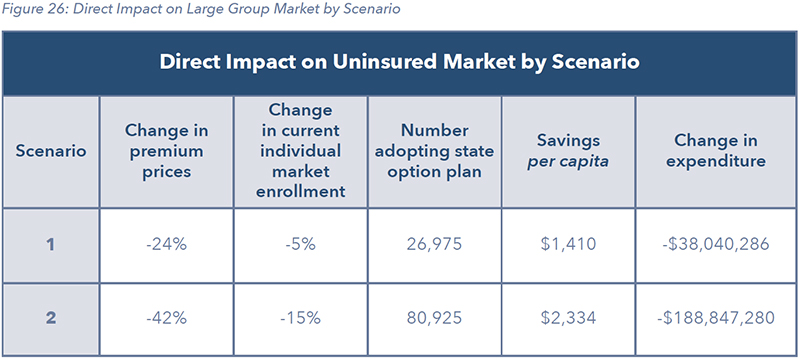

As found in the Milliman study, a new state option that reimbursed providers at 100% of Medicare rates could be offered to consumers at prices between 24% and 42% below current market rates. Associated with these two levels of price reductions, Milliman found a range of impacts to the other areas of health care coverage. Figure 18 shows the assumptions for how other types of coverage would be directly impacted under each scenario.

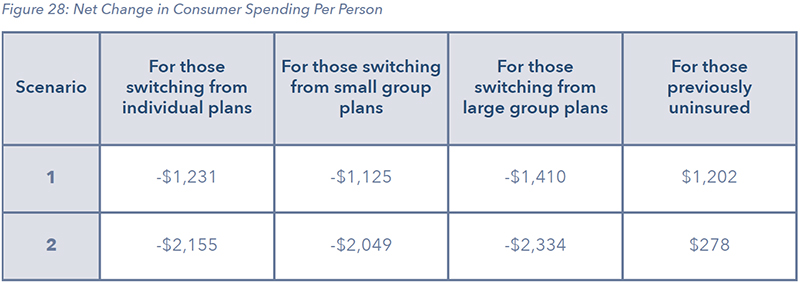

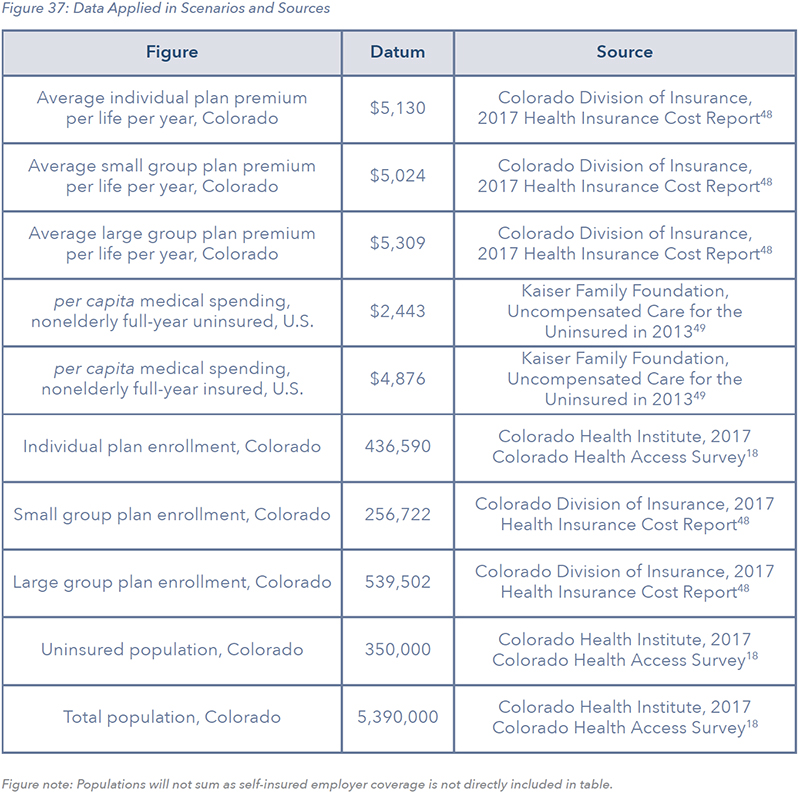

Using the average premium per life per year data from the 2017 Health Insurance Cost Report, a change in net expenditures, or medical revenue, was calculated based upon the assumed percentage reduction in prices for each scenario, and the total number of people who transition from each market. For those that transition from existing coverage, the net impact is a reduction in health care expenditures.

For those that transition from being uninsured, the impact is a positive impact on health care expenditures. Previous research from the Kaiser Family Foundation suggested uninsured individuals spend roughly half as much as those that are insured on average. Therefore, for the purpose of modeling, the net increase in expenditures by the uninsured population transitioning to the state option was the difference between what they are assumed to be currently spending compared to the price of the state option. The net change in spending on a per-individual basis can be found in Figure 28.

IMPACT ON THE UNINSURED

The most natural target group for a state option would be the currently uninsured. Given 78.4% of uninsured Coloradans indicated in 2017 that high cost is a reason for not having insurance, the potential savings delivered by price-capping could entice more people to purchase insurance.

IMPACT ON THE INDIVIDUAL MARKET

Other targets for this state option are people who currently have insurance through the individual market on relatively high-cost plans and would choose to switch to new lower-price state option plans. The extent to which this occurs will, of course, depend upon the actual savings of the plan. According to research from Milliman in Washington state, between 80% and 100% of people in the individual market can be expected to switch to Cascade Care. The tables below show the number of individuals in Colorado who have health insurance on the individual market and the impacts of a state option upon the individual market detailed by the several scenarios.

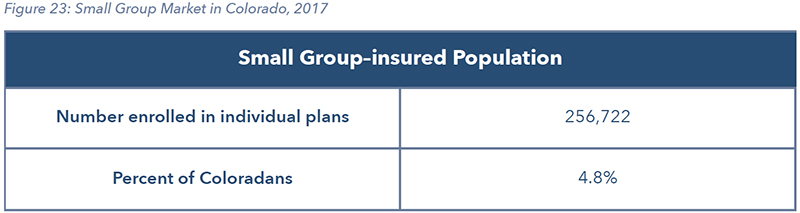

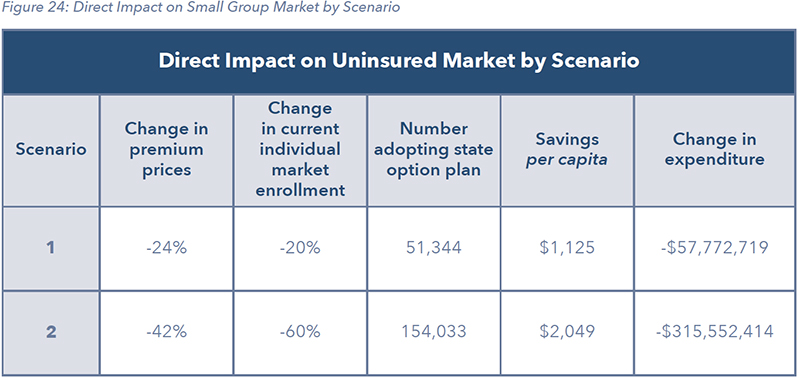

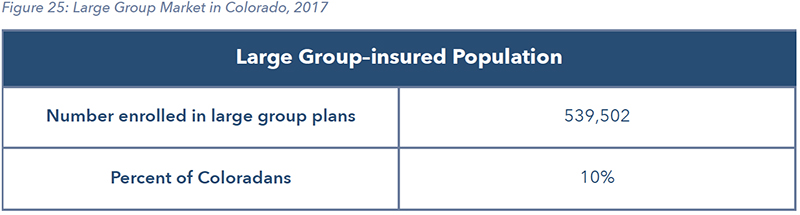

Also identified by the Milliman report was the potential for employers, particularly those in the small group market, but to lesser extent those in the large group market, to shift their employees to a less expensive state option plan.

IMPACT ON THE SMALL GROUP MARKET

IMPACT ON THE LARGE GROUP MARKET

NET DIRECT IMPACT

As described in the previous section, the impact on direct health care expenditures varies depending on which part of the market is impacted. There will be an increase in revenue to providers from people who join the state option plan that were previously uninsured. There will be a decrease in medical revenue to providers from people on state option plans

This complex net effect will play out across every region of the state and will affect each region differently. Below are the net impacts upon medical provider revenue corresponding with the two scenarios resulting from shifts in each coverage market.

These changes in expenditure represent both losses in industry revenue and savings on average to consumers. Changes to annual consumer spending on health care per capita estimated by the scenarios are as follow:

While the individuals who are currently insured and choose to switch to the state option will be doing so because of the lower cost, their actual costs of care are assumed to not change. Therefore, the aggregate of the consumers’ savings represents a net expenditure reduction to various health care services.

DYNAMIC ECONOMIC IMPACTS

Following the direct impacts to each health insurance market, through running several economic impact simulations, a sense of the potential impacts can be better understood. All four scenarios, shown in the direct impact section, produce a direct savings for some Coloradans, without lowering the expenses associated with providing their care, thereby lowering the medical revenue going to the state’s health care providers.

The dynamic economic impacts to the Colorado economy, are the results of simulation modeling done using the PI+ model developed by the private company REMI. The simulations are based on the net expenditure results shown in Figure 29. Given the net expenditures represent a loss in health care spending without a change in the underlying costs, health care providers will be faced with several decisions. The two primary decisions will be around two options:

- Cut costs

- Pass on costs

Option 1: CUT Costs

To the extent it is possible to cut costs, these cuts will translate to changes such as lower labor costs and delayed upgrades in buildings or equipment. Given the very thin margins for some providers, it may also mean certain facilities find they can no longer operate in different parts of the state. Hospitals, doctors, and specialists may also opt to further shift costs the remaining private insurance market, which without an individual market would come down to employers sponsored insurance and employers who self-insure.

Option 2: PASS on Costs

There already exists a significant cost shift within the health care market. When looking at data related to hospitals, an increase in prices for private insurers has increased at the same time the level of under compensating from public payers has also increased following the expansion of Medicaid. Every provider will be faced with a different situation and varying ability to recoup additional losses from remaining private insurance customers. This second option assumes that 100% of the lower expenditures from the state option patients, will be recovered through higher prices charged to the remaining private insurance market. Given that in the scenarios, 80% to 100% of the current individual insurance market is in the state option, virtually all the costs will be passed on to the remaining employer-sponsored health care market.

To simulate the reduction in prices to consumers who switch to the state option plan, away from some other form of private insurance, the ability to purchase other goods and services in Colorado is represented as an increase in consumer spending on all personal consumer expenditure items outside of health care. This increase in consumption was then coupled with either an across the board cut in costs or the passing on of higher costs to the remaining private insurance market. An across the board cut was modeled as a reduction in consumer spending on healthcare-related personal consumer expenditure items. The passing on of higher costs was modeled as an increase in production costs for all industries.

The following tables illustrate the state-level economic impacts of those two possible outcomes. It is likely the case the actual outcome of the decisions of each health care provider is somewhere in the middle, but these simulations are meant to give a deeper understanding of the tradeoffs.

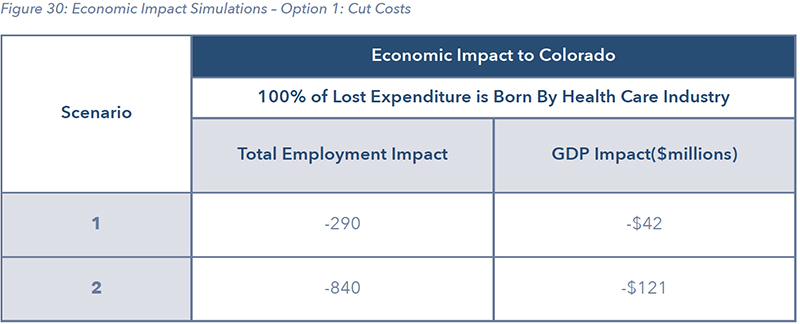

Figure 30 and 31 show the economic impact across jobs, GDP and real disposable income for each scenario, depending on whether the net decline in medical revenue is passed on to the remaining private insurance market, or if it translates to a proportional decrease in spending across each health care consumption category.

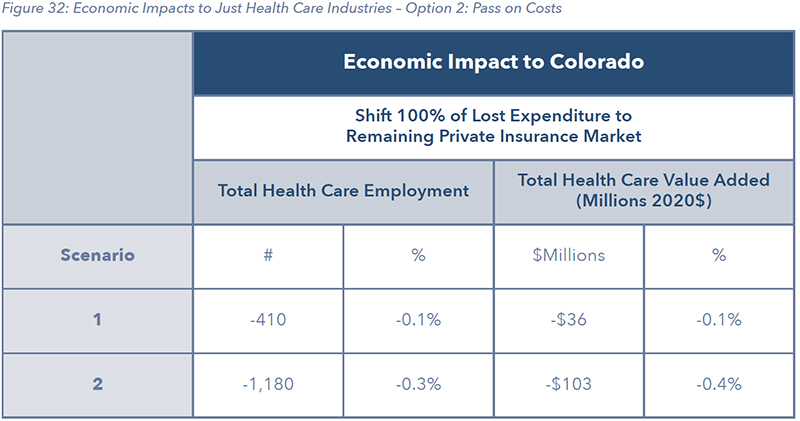

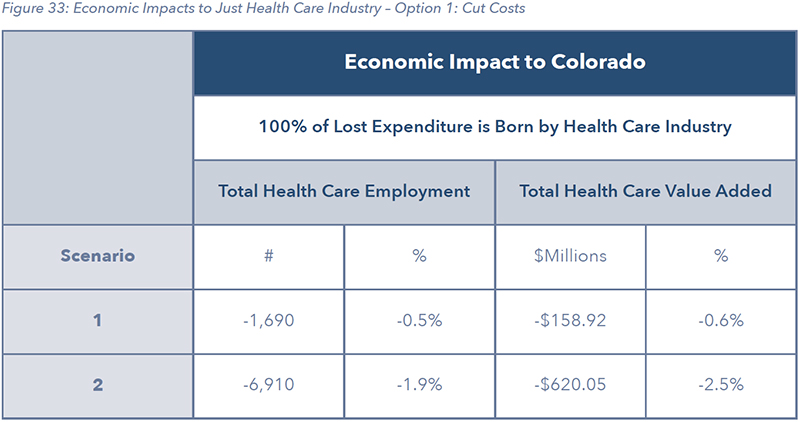

Included in the modeling is an increase in consumer spending on all other categories of consumption, as consumers who previously were paying higher premiums under private insurance, now pay less under the state option. For this reason, the overall economic impacts reflect this adjustment. However, when looking at just the health care sector, more insight can be determined. If costs are shifted to the remaining insurance market, there is much less of an impact on health care as costs are borne primarily by other businesses as shown in Figure 32. If the decrease in net revenue equates to a reduction in services and medical revenue, then even as there is a more muted impact on the economy as a result of some consumption reallocation, the health care industry takes a much harder hit as shown in Figure 33.

The total employment results in Figure 32 and 33 represent all jobs in the health care industry. Many of those jobs are not considered health care occupations as they don’t directly work in a medical capacity. That covers such jobs as custodians at hospitals or administrators that don’t deal with patients. Figure 34 shows the impact on healthcare-related occupations, which are actual medical related professions. They are shown for each scenario, assuming 100% of the lost medical revenue amounts to a reduction in health care expenditures and no costs are passed on.

IMPACT IN RURAL COMMUNITIES

When looking at the impact of the state option scenarios at a statewide level, it is possible to overlook the likely more pronounced impacts occurring at a sub-state level. The impact of a state option established fixed, below-market rates could have more pronounced impacts on different parts of the state, particularly rural parts, for several reasons:

- Given both costs and prices are relatively higher, an equivalent percentage reduction in premiums could have a larger net impact.

- The share of remaining private insurance holders could be smaller.

- The relative size of the health care sector as part of the regional economy could be larger.

For those reasons, a similar approach as described at the statewide level in the previous section was replicated for Colorado insurance rating regions 9 and 8. This area covers all counties outside of the 7 state MSA’s and could be considered most of rural Colorado. Both regions contain large portions of their jurisdictions designated as medically underserved indicating they already have issues with medical service shortages47.

While the recent research by Navigant Consulting on the potential impacts of a state option on rural hospitals does not specify specific sub-state regions, it does reinforce the issue rural health care providers are already facing significant challenges with just staying in business. Their findings indicate a state option could result in a net loss in revenue to rural hospitals of 4.1% to 21.2%, causing 8 to 13 hospitals to go out of business3.

RURAL COLORADO SCENARIOS – HEALTH INSURANCE RATING AREAS 8 AND 9

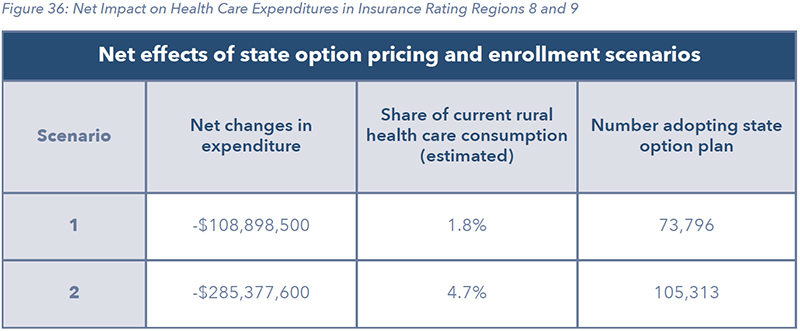

Figures 35 through 37 show similar results to the statewide analysis without the macroeconomic modeling. Figure 36 shows the range of the net decrease in health care expenditures between the two scenarios. While the percent reduction in premiums was assumed to be the same in both the statewide modeling and this regional modeling, the potential percentage decrease in medical revenue is much larger.

Large sections of Colorado, primarily outside of the state’s urban areas, currently struggle to attract and retain sufficient levels of medical professionals. At the same time, hospitals and other large medical facilities are significant employers and sources of economic activity in communities that may not be experiencing growth in other sectors. Therefore, a state option that increases the under-compensation of medical providers, threatens both the availability of healthcare-related services in rural communities but also significant economic drivers. While this same effect is present in urban areas, it is disproportionately felt in more rural markets.

Figure 37 is a breakdown of coverage and price data used to develop the economic modeling scenarios. While the scenarios included in this report are set up to better understand the tradeoffs of a state option, given the large discrepancies between some sources as it relates to coverage, policymakers and the public should understand the limitations with even the baseline data. The 2017 CHAS survey, though it reports most relevant data in lesser detail, does not present similar contradictions to those from the Colorado DOI’s 2017 Health Insurance Cost Report.

STATE OPTION GUARDRAILS: POLICY IDEAS TO MITIGATE UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

The draft state option proposal is expected to be unveiled by the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing (HCPF) and the Division of Insurance (DOI) on September 30th, with the final proposal coming November 15. Given the stakes and economic tradeoffs, several guiding principles should be considered with the development of this policy. These guiding principles can also serve as tools by which the general public, employers, and voters can also evaluate the proposed plan once it is revealed.

A state option enacted by the state government must carefully balance addressing high costs while mitigating unintended consequences and not sacrificing quality of or access to health care.

- State option carriers should play by the same rules as everyone else

- Allow for negotiable rates for reimbursement or expenses- no rate caps

- Keep the “state option” an option

- Start small and let other state policy changes take effect

STATE OPTION CARRIERS SHOULD PLAY BY THE SAME RULES AS EVERYONE ELSE

The role of government should be to set the rules for all stakeholders to adhere to. If the state embraces a different set of rules for a state option than for private health insurance, competition and consumer access may be adversely affected. The potential creation of an entity operating outside these rules would undermine the ability of private insurance to compete.

Currently, health insurers work within one of the most heavily regulated markets, under extensive federal and state laws including network adequacy requirements and minimum benefit requirements. If the state embraces a different set of rules for a state option than for private health insurance, competition and consumer choice may be adversely affected.

Instead of encouraging competition and choice, a state option operating under an inequitable playing field with private insurers and providers, may further encourage them to reduce services or even exit certain markets, further exacerbating the lack of choices and services offered in rural counties and possibly reducing access to care, which is currently relatively good50.

ALLOW FOR NEGOTIABLE AND FLEXIBLE RATES FOR REIMBURSEMENT OR EXPENSES

The costs related to delivering care vary widely across the state and across providers51. The decision of HCPF and the DOI to include the underlying cost of care in the definition of affordability for the state option is a positive, though insufficient, step toward addressing the underlying cost of care. As such, establishing a fixed ratio of payments relative to existing public insurance fails to recognize the underlying cost of care.

Moreover, any state option merely capping prices and reimbursement rates, will result in fewer providers being willing to accept the insurance. Additionally, savings could ensue from the imposition of such plans, as demonstrated by Cascade Care, may not be significant52. The incentive for mandatory insurer participation may increase if adequate networks cannot be built, which poses significant risks to the continued viability of providers across the state53.

As the demand for health care is inelastic and access to care is critical in life-and-death moments, any state option with the potential to adversely affect access to and quality of care due to reimbursement caps would both run contrary to the stated goals of HCPF in designing a state option and would also undercut innovative approaches and payment reforms that have already been implemented both within the government and private sectors54 and shown to be successful in reducing costs.

KEEP THE “STATE OPTION” AN OPTION

If the state option is truly to remain an option, it must avoid mandating participation by insurers and/or providers. If prices are set below market prices and providers are also required to accept patients under a state option plan, then costs will merely be further shifted to consumers receiving insurance through other means. If this shift is unable to compensate for lower revenues, providers may further reduce services in less-served areas55 and ultimately exit the market.

The bill establishing Cascade Care in Washington stipulates a report is to be delivered to the legislature by December 1, 2023, which evaluates the impact of allowing only Cascade Care, the public option, to be offered on the individual market. This means by as early as 2025, the only insurance plans sold on the individual market in Washington could be the more heavily regulated “public option” plans paying providers substantially less than what they currently charge.

START SMALL AND LET OTHER STATE POLICY CHANGES TAKE EFFECT

Over the past two years, the state has taken various measures designed to place downward pressure on health care costs. While the results remain to be seen, estimates for some reforms suggest they could be significant. For example, the reinsurance program authorized by HB19- 1168 and recently approved by the federal government has been suggested it will reduce premiums by roughly 18% on average and as much as 35% in some parts of the state compared to 2020 baseline premiums.

Additionally, the federal government has announced the unprecedented approval of a program that will allow the state to import prescription drugs from Canada56. Finally, a working group called the Primary Care Payment Reform Collaborative is working to find ways to increase investments and reduce costs in primary care, with annual recommendations due every December 15th. These reforms are just a few examples of the many recently passed that may prove to be disruptive over the coming years. The state should avoid adding to this disruption through a state option.

CONCLUSION

Due to recent federal and state policy changes and demographic trends, health care coverage in Colorado has changed significantly over the past 5 years. Through the Affordable Care Act and the expansion of Medicaid, the uninsured rate in Colorado has declined significantly. With the overall aging of the population, the number and share of Coloradans on Medicare has also increased. Despite strong job growth, the total number of Coloradans on employer sponsored insurance or covered in the individual market has gone down.

By one measure, public payers cover 69% of the total expenses for their enrollees. This leaves health care providers with recouping costs through charging higher prices to the remaining private insurance market. As the number of individuals on public coverage has increased, private insurance premium growth has far outpaced income growth and made it more challenging for those that don’t qualify for Medicaid or Medicare to be able to afford private insurance coverage. At the same time over 1,000,000 Coloradans live in areas designated as medically underserved due to a shortage in certain health care professionals.

The task before the state Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF) and the Division of Insurance (DOI) is to develop a proposal to implement a state option for health coverage. While the exact design is currently unknown, discussion from stakeholder meetings, and other state proposals on the same topic, highlight the risks in further disrupting health care markets in this way. When examining the potential impacts of a state option, the evidence is clear – how much power the state chooses to wield will determine just how disruptive the policy is. Adopting a state option that offers premiums remarkably below market rates could further exacerbate the trends in costs for private insurance and health care professional shortages given it doesn’t address underlying cost drivers.

The purpose of this research is to take a deep dive into the underlying issue and to give others a better framework for how to understand the potential impacts. To estimate a range of potential impacts of a state option in Colorado, this report covers two scenarios, based upon an assumed 24% and 42% reduction in insurance premiums relative to the current individual market. These scenarios mimic the findings of a Milliman consulting report on an early version of the state option recently adopted in Washington state. While the scenarios and results are not intended to replace a full actuarial analysis of the final Colorado proposal, they hope to shed light on some of the more concerning elements of a state option design.

The findings from the scenarios demonstrate how further shifts away from private insurance markets towards the state option that offers significantly lower reimbursement rates to providers would result in significant losses in medical revenues. Those estimated losses of between $494 million to $1.4 billion will leave providers with a trade-off, either increase prices on the remaining private insurance market or modify or cut back on services that could impact quality and access.

Through using the dynamic economic simulation model PI+, developed by REMI, a potential range of impacts can be determined. If health care providers choose not to pass on an of the losses and bear the full costs, the impacts could range from between 1,500 and 4,500 fewer health care related jobs such as physicians, nurses and therapists. If health care providers choose to pass on 100% of the costs to the remaining private insurance market, primarily the employer market, the overall economic impact on jobs could range from 2,900 to 8,300 fewer jobs.

There are clear steps regulators and policymakers can take to avoid the potential for greater economic disruption within our health care system, and economy. Avoiding more heavy-handed mandates that further distort the health insurance market should be avoided, while a more targeted approach to address cost drivers should continue to be explored.

REFERENCES

- J. Tolbert, M. Diaz, C. Hall and S. Mengistu, “State Actions to Improve the Affordability of Health Insurance in the Individual Market,” Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019.

- Colorado Healthcare Affordability and Sustainability Enterprise, “Colorado Healthcare Affordability and Sustainability Enterprise Annual Report,” 2019.

- J. Goldsmith and J. Leibach, “THE POTENTIAL IMPACT OF A MEDICARE PUBLIC OPTION ON U.S. RURAL HOSPITALS AND COMMUNITIES: A SCENARIO ANALYSIS,” Navigant, 2019.

- L. König, A. Saavoss, S. Soltoff, B. Demiralp and J. Xu, “The Impact of Medicare-X Choice on Coverage, Healthcare Use, and Hospitals,” KNG Health Consulting, 2019.

- Health Care Policy and Financing, “Proposal for Affordable Health Coverage Option Stakeholder Meeting – 5-29-2019,” YouTube, Denver, 2019.

- “Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs),” Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018.

- A. Spanko, “Using Community Colleges to Fight the Nursing Shortage,” Skilled Nursing News, 5 February 2018.

- “Health Care Expenditures per Capita by State of Residence,” Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014.

- “America’s Best Hospitals for 2019,” healthgrades, 2019.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2017. [Online].

- REMI PI+ Denver and Rest of Colorado v2.3.1 (Build 5112), Gross Domestic Product: Colorado Baseline.

- “State Revenue & Budget: 2019 Appropriations History,” Joint Budget Committee Staff.

- S. R. C. a. S. L. H. David C. Radley, “Commonwealth Fund,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://scorecard.commonwealthfund.org/.

- U.S News and World Report , “Colorado Rankings,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/colorado.

- United Health Foundation, “America’s Health Rankings composite measure, 2018,” 2018.

- C. e. a. AInsworth, “ACSM American Fitness Index 2018 Rankings Summary Report,” American College of Sports Medicine, 2018.

- RAND Corporation, “RAND Corporation,” [Online]. Available: https://www.rand.org/topics/health-careaccess.html. [Accessed 29 June 2019].

- Colorado Health Institute, “Colorado Health Institute Colorado Health Access Survey, 2017,” 2017.

- U. C. f. M. &. M. Services, “Medicaid expansion & what it means for you,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/medicaid-expansion-and-you/.

- “Colorado Health Insurance Brokers,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.coloradohealthinsurancebrokers.com/eligible-subsidy/. [Accessed August 2019].

- Colorado Health Institute, “Colorado’s Eligible but Not Enrolled Population Holding Steady,” 2018.

- “2018 Annual Report,” Colorado Rural health Center – The State Office of Rural Health.

- e. a. Bontrager, “Colorado’s New Normal: State Maintains Historic Health Insurance Gains,” Colorado Health Institute, 2017.

- “REGIONAL PRICE VARIATION FOR COMMON PROCEDURES, COMMERCIAL INSURERS,” Center for Improving Value in Health Care, 2017.

- “Health Care Costs and Hospitals: Drivers and Opportunities,” Colorado Hospital Association, 2019.

- M. Nardo, “HB19-1004 Final Fiscal Note,” Denver, 2019.

- C. D. o. H. C. P. &. Financing, “Proposal for Affordable Health Coverage Option,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/proposal-affordable-health-coverage-option.

- M. Andrews, “New Mexico Eyes A ‘Medicaid Buy-In’ Plan To Insure More Residents,” National Public Radio, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/25/696626244/new-mexico-eyes-a-medicaid-buy-in-plan-to-insure-more-residents. [Accessed 2019].

- C. Brooks-LaSure, P. Boozang, H. Davis and A. Traube, “Evaluating Medicaid Buy-in Options for New Mexico,” Manatt Health, 2018.

- C. Brooks-LaSure, P. Boozang, H. Davis and A. Traube, “Quantitative Evaluation of a Targeted Medicaid Buy-In for New Mexico,” Manatt Health, 2019.

- New Mexico Office of the Governor, “Gov. Lujan Grisham delivers on increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates: $60 million for targeted provider rate increases,” State of New Mexico, Santa Fe, 2019.

- Washington State Legislature, SB 5526-2019-20: Increasing the availability of quality, affordable health coverage in the individual market, Olympia: State of Washington, 2019.

- Washington Health Plan Finder, “Cascade Care Implementation: Background FAQs,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/HBE_ATE_CC_190808_Cascade-Care-Implementation-Background.pdf.

- M. Staff, “How Inslee plans to pay for and operate Cascade Care,” KIRO Radio, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://mynorthwest.com/1239973/inslee-pay-cascade-care-washington/?.

- D. Goldberg and R. Pradhan, “5 key questions about the country’s first public option,” POLITICO, 14 May 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.politico.com/story/2019/05/14/washington-public-healthplans-1431816.

- W. S. Legislature, “SENATE BILL REPORT E2SHB 1523,” State of Washington, Olympia, 2019.

- A. Cassidy, “Basic Health Program,” Health Affairs, 15 November 2012.

- C. D. o. H. c. P. &. Financing, “State Option for Health Care Coverage- Division of Insurance / Dept. of Health Care Policy & Financing Stakeholder Meeting June 13, 2019,” Division of Insurance / Dept. of Health Care Policy & Financing, Denver, 2019.

- Colorado Health Institute, “The Competition Conundrum,” Colorado Health Institute, 2019.

- Medicaid.gov, “Basic Health Program,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), [Online]. Available: https://www.medicaid.gov/basic-health-program/index.html.

- E. Curran, “Proposed Rule on Basic Health Program Impedes States’ Progress,” Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center on Health Insurance Reforms, 25 April 2019. [Online]. Available: http://chirblog.org/proposed-rule-basic-health-program-impedes-states-progress/.

- Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing, “Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+),” Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing, [Online]. Available: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/child-health-plan-plus.

- M. A. Hall and K. Swartz, “Establishing Health Insurance Exchanges: Three States’ Progress,” The Commonwealth Fund, 2012.

- R. King, “Health program proposal may cause New York, Minnesota to lose millions,” Modern Healthcare, 19 March 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/government/health-programproposal-may-cause-new-york-minnesota-lose-millions.

- S. Corlette, J. Giovanelli, J. Lerche and S. Miskell, “Why Are Many Co-ops Failing? How New Nonprofit Health Plans Have Responded to Market Competition,” The Commonwealth Fund, 2015.

- Milliman, “Evaluating potential health benefits from Cascade Care,” 2019.

- Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment, Health Professional Shortage Area maps and data, 2015.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, “2017 Health Insurance Cost Report,” 2017.

- T. A. Coughlin, J. Holahan, K. Caswell and M. McGrath, “Uncompensated Care for the Uninsured in 2013: A Detailed Examination,” Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014.

- Colorado Health Institute, “2019 Medicaid and Commercial Access to Care Index,” Colorado Health Institute, 2019.

- Health Coverage Colorado, “Fact Check: Should the price of healthcare services be benchmarked against Medicare reimbursement rates?,” Health Coverage Colorado, 7 August 2019. [Online]. Available: https://healthcarecoverageco.com/fact-check-should-the-price-of-healthcare-services-be-benchmarkedagainst-medicare-reimbursement-rates/.