Analysis of the Cost and Risk of Financial Insolvency for a Colorado Paid Leave Program

ABOUT THE REMI PARTNERSHIP

A partnership of public and private organizations announced in July 2013 the formation of a collaboration to provide Colorado lawmakers, policymakers, business leaders, and citizens, with greater insight into the economic impact of public policy decisions that face the state and surrounding regions. The parties involved include the Colorado Association of REALTORS®, the Colorado Bankers Association, Colorado Concern, Common Sense Policy Roundtable and Denver South Economic Development Partnership. This consortium meets monthly to discuss pressing economic issues impacting the state and to prioritize and manage its independent research efforts.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

To successfully create a new government program, policymakers need a clear understanding of how much it will cost and how it will be funded over time. Since policymakers cannot see the future, they must instead make assumptions about future costs and the funding sources that will be available to cover those costs.

If those assumptions about future costs and funding sources are realistic and affordable, the new government program has a chance to succeed. But if those assumptions are unrealistic and unaffordable, there is a danger that policymakers will set the program up to fail, no matter how good their intentions may be.

The consequences of that failure can have serious impacts on other budget priorities, not to mention working families and businesses across the broader economy. For this reason, the assumptions that go into major legislative proposals deserve scrutiny.

This report examines the assumptions behind SB-188, a bill to create a state-run Family Medical Leave Insurance Program in Colorado. While the intentions behind the program may be good, the assumptions that support the measure are questionable, raising the risk of a costly failure of the program.

In light of these questionable assumptions, and the high costs of a program failure, lawmakers should consider a broader range of policy options.

As currently proposed, SB-188 would require workers and businesses all across Colorado to pay into the state-run leave program, even in cases where paid leave is already provided. Rather than jump to the conclusion that a mandatory state program is the only option, lawmakers should study the current availability of paid family and medical leave in Colorado and explore different ways to expand this availability.

Underestimating program demand and costs

There is reason to believe the authors and supporters of SB-188 have underestimated the potential utilization rate in the taxpayer-funded family leave program, also known as the claims frequency rate (CFR) used by private insurance companies. This is a critical assumption because the number of people claiming benefits under the program drives the total cost of the program.

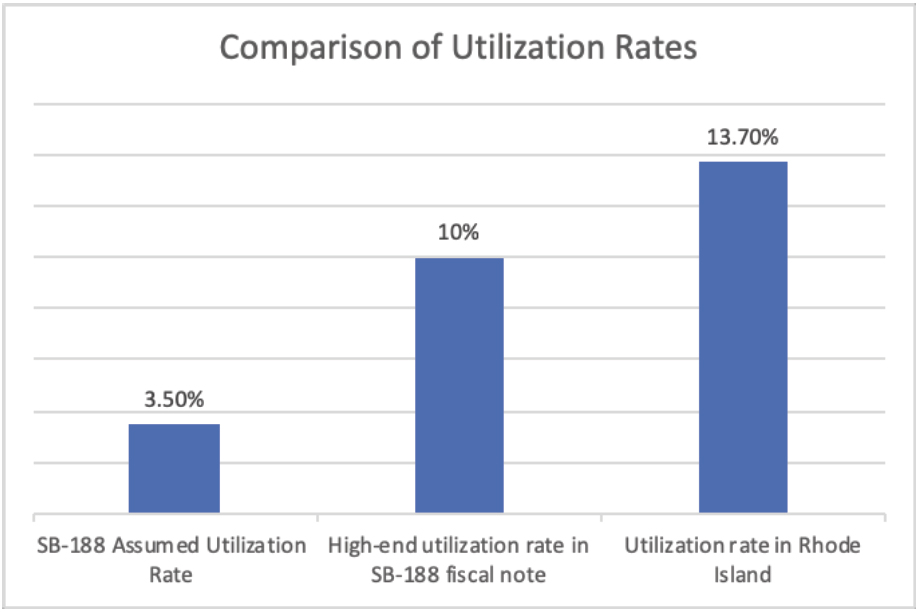

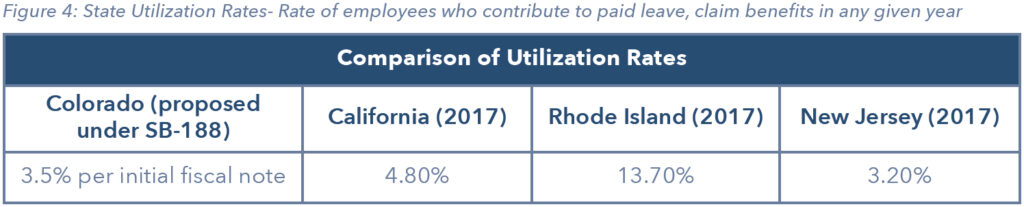

Rhode Island implemented a similar taxpayer-funded leave program which has a utilization rate 13.7%. But cost estimates for SB-188 depend on a much lower utilization rate, just 3.5%. The same cost estimates, contained in a fiscal note prepared by Legislative Council staff, concede the actual utilization rate could be much higher, up to around 10%. But no cost estimate was prepared for this scenario.

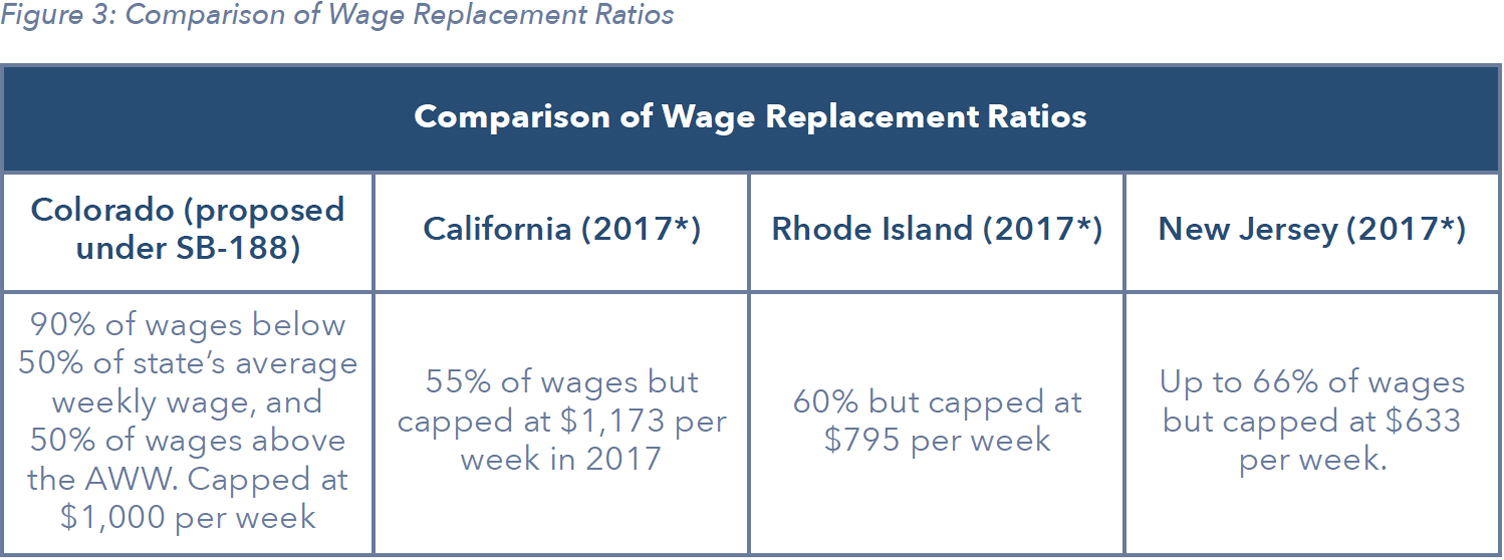

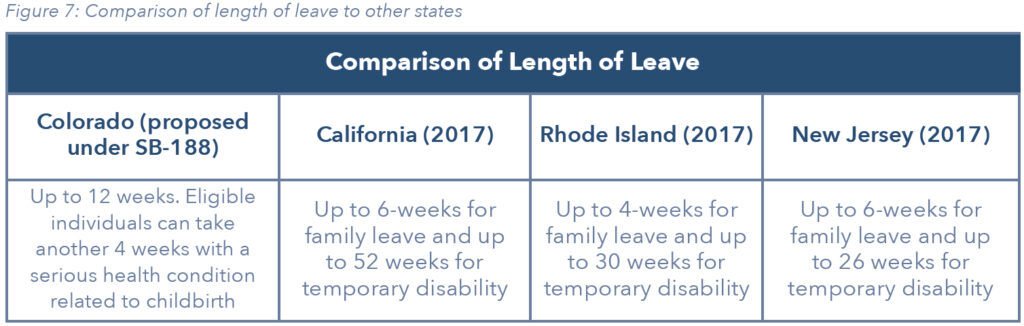

Given the experience in Rhode Island, 10% may also underestimate the actual utilization rate in SB-188’s paid leave program, because Colorado’s proposed benefits are more generous than those of other states. SB-188 expands the scope for qualifying leave by allowing for the care of individuals outside one’s immediate family. On top of that, SB-188’s wage replacement rate is higher and the maximum weekly benefit is 25% higher than what is offered in Rhode Island, where the utilization rate is 13.7%, almost four times the rate assumed for SB-188’s cost estimates.

A review of utilization rates in other states like California and New Jersey, and research conducted by the University of Denver on a paid leave proposal very similar to SB-188, suggest higher utilization rates than 3.5%. Only New Jersey, which has provided significantly lower benefits than what SB-188 proposes, comes close with a utilization rate of 3.2%.

This is critically important, because even at 3.5%, SB-188 is expected to cost taxpayers roughly $950 million per year. If the utilization rate climbs higher, the real costs of SB-188 will grow significantly more than lawmakers anticipate. The risk of massive underfunding and financial failure is meaningful.

Higher costs impact state budget, economy and jobs

SB-188 imposes a .64% payroll premium on employers and employees to pay for the family leave program. According to budget estimates accompanying the bill, this premium will raise over $957 million per year by FY-2022-23, the first full fiscal year in which benefits are paid. According to the same estimates, this total should be sufficient to cover administrative costs and benefit payments under the SB-188 paid leave program.

But these estimates rely on the assumed 3.5% utilization rate, when the available research suggests the utilization rate will likely be higher. In fact, SB-188 has already been amended to prepare, at least partially, for such a scenario. The amended bill, released March 14, would allow the director of the newly created leave program to increase payroll premiums from .64% to a maximum of .99% to help cover the cost of benefits.

In light of these developments, the costs of higher-than-assumed utilization rates deserve to be explored.

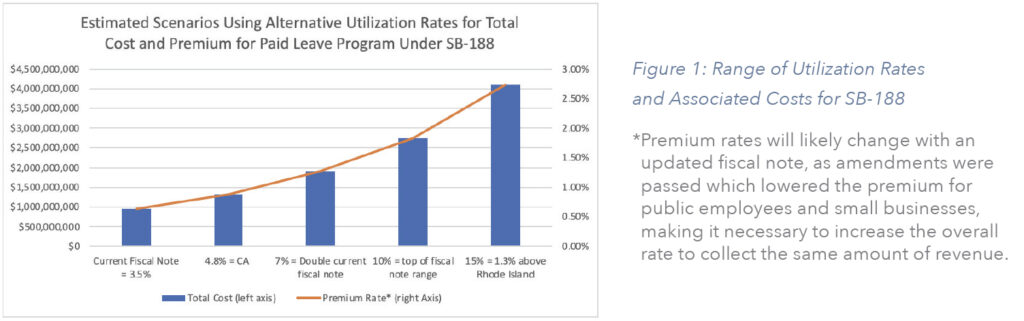

For this report, we examined the likely cost of SB-188 to taxpayers under a range of higher utilization rates, and some of the reasons why the rate may be higher than currently estimated for SB-188. The chart below shows the range of costs associated with utilization rates of 3.5%, 4.8%, 7%, 10% and 15%. Rates of 3.5%, 4.8%, 7% and 10% are within the range of possibilities discussed by Legislative Council in the fiscal note, yet still much lower than the 13.7% reported in Rhode Island. Given the benefit structure of SB-188 is more generous than any other state, the utilization rate of 15% was also included given the possibility that Rhode Island is not even an upper bound.

Under a 7% utilization rate, the premiums charged to employees and employers would have to double, from $957 million to more than $1.9 billion.

This would significantly exceed the amount that could be raised by the maximum .99% payroll premium that can lawfully be charged under SB-188. To prevent the paid leave program from collapsing, lawmakers would face a challenge to change the law to allow for payroll premiums to increase to at least 1.28%, or come up with another surcharge to cover the additional $950 million in costs. As an enterprise, the agency would be restricted in how much revenue it could receive from the general fund.

A budget challenge of this size will not just be felt in state government, it will have broader economic impacts too.

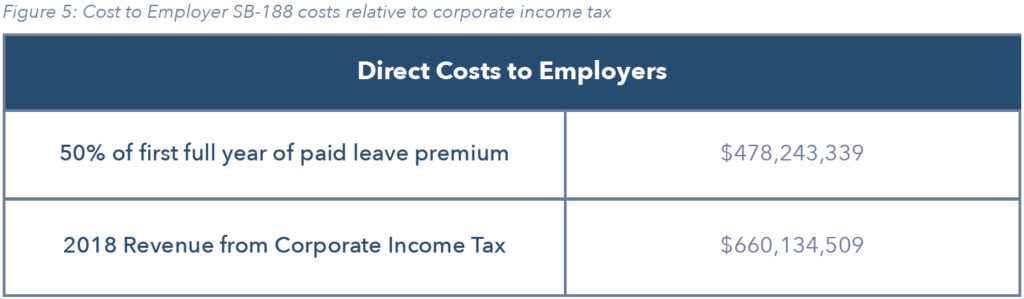

For example, even with a low utilization rate of 3.5%, the premiums paid by employers into the SB-188 paid leave program would total $478 million per year. Currently, the amount collected under Colorado’s corporate income tax is just over $600 million. This means even with a low utilization rate, SB-188 would effectively increase the tax burden on businesses in Colorado by roughly 70%. If you assume a higher utilization of 7% under SB-188, that effective increase climbs to 140%.

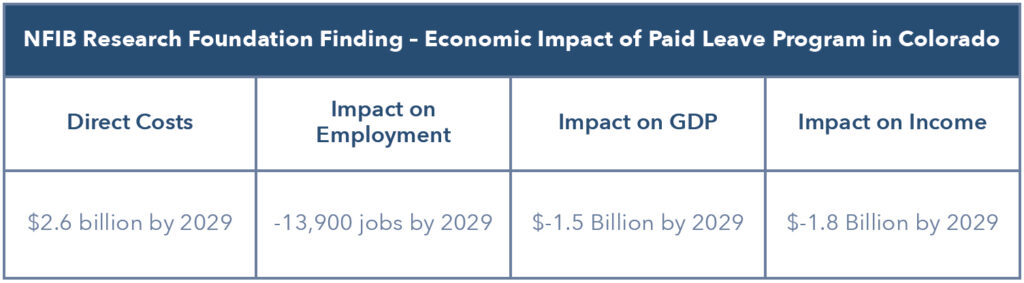

Given the size and scope of these potential impacts, Colorado’s business community has been monitoring the potential economywide impacts of taxpayer-funded leave programs. In January, the research foundation of the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB) used the REMI PI+ model to assess the impacts of such a program, with costs split 50/50 between employer and employee, the same formula used in SB-188.

The NFIB study predicted the loss of almost 14,000 jobs in Colorado and a decline in real disposable income of $1.8 billion across state by 2029, among other major costs.

The NFIB analysis included direct costs that are very similar to those estimated in the SB-188’s fiscal note. The analysis also factored in the economic impact of benefits paid to program participants while on leave and conservatively estimated zero administrative costs, effectively putting 100% of the premiums paid into the hands of program participants.

However, even with these parameters, the NFIB study still found net negative economic impacts from the loss of worker incomes and increase in business costs from the creation of a mandated, taxpayer-funded paid family leave program in Colorado.

Avoiding the mistakes of the past

By questioning the assumptions behind a proposed new government program like SB-188, policymakers can give themselves a chance to avoid making the same mistakes of the past.

Colorado’s public pension crisis, for example, is a textbook example of good intentions being dragged down by questionable assumptions, resulting in a major and costly program failure. In 2018, Colorado lawmakers committed to an unprecedented $225 million annual payment from the general fund to the Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA) to help rescue PERA from an unfunded liability of at least $32 billion.

The rescue effort, which also included higher contribution rates from public employees, school districts and local governments, followed more than a decade of rising taxpayer support for the PERA system, from roughly $800 million per year to $1.6 billion per year. School districts in particular complained that rising pension obligations were draining their budgets, thwarting efforts to increase teacher pay, and pushing more schools to operate on a reduced 4-day schedule.

Importantly, unlike PERA, the payments made to claimants of paid leave are made almost immediately following the claim, and the agency is only required to collect 50% more than the following years expected claims. This means that the program could face a cash flow crisis as claims rates could spike over short periods of time.

The 2018 PERA rescue was the fourth of its kind in less than 20 years. Each one of those earlier reforms was supposed to provide a long-term fix to PERA’s financial challenges. But despite the good intentions of all involved, assumptions about benefit costs and the ability of pension contributions and investment returns to keep up with those costs turned out to be wrong.

A similar example of unexpected and costly impacts can be found in Colorado’s unemployment insurance program. In the wake of 2001 recession and the 2008 financial crisis, a series of surcharges were added to the base rates paid by employers. Those surcharges were in effect from 2004 to 2012 in order to maintain the solvency of the state’s unemployment insurance fund. For example, in 2009, the base rate brought in $125 million, with an additional $215 million collected in surcharges from employers.

However, after the surcharges ended in 2012, higher costs above the base rate persisted. A bond principal rate was added to the base rate paid by employers. This means from 2004 to 2017, Colorado employers paid much higher than expected unemployment insurance rates.

Originally, the higher rates were intended to bolster the state’s unemployment fund during times of recession. But these higher rates continued to persist long after the recession ended and even during periods of record low unemployment in Colorado.

Conclusion

Balancing the demands of a job, staying healthy and taking care of family responsibilities is a challenge for many Colorado workers. While many employers offer paid leave and other policies to help their employees find the right balance, not all can afford to do so presently.

Expanding the availability of paid family and medical leave is a worthy public policy goal. To find workable and sustainable solutions over the long term, policymakers should closely examine the barriers to providing these benefits through private insurance and look at a range of options for overcoming those barriers, including existing regulations or new fiscal incentives. Assuming that only one option can work, especially a one-size-fits-all government program, would be a mistake.

The intentions behind this proposal may be good. But for the program to succeed, it must be based on realistic assumptions about the need for a state-run program, how much that program will cost and where the funds for the program will come from.

There is strong reason to believe the assumptions behind SB-188 are questionable. Left unchecked, the use of these assumptions could set up the proposed paid leave program for failure. The cost of that failure, measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars every year, would be felt across the state budget and across the economy.

There are also legitimate concerns about how much the paid leave program will add to the tax burden of employers and employees in Colorado, since the funds for the program will be taken directly from their payrolls. The additional costs to businesses, and the loss of spending power from employees, could lead to significant job losses and greater job insecurity.

These unintended consequences, along with the impacts of questionable cost assumptions, undermine the good intentions behind SB-188. Rather than be ignored, these concerns should be given serious attention to prevent the mistakes of the past from being repeated and protect working families in Colorado from the associated impacts.

If legislators are determined to push ahead with SB-188, however, then asking voters to approve the legislation may be a worthy endeavor. Putting aside the arguments about whether payroll premiums are a tax that requires voter approval, a statewide debate would provide an opportunity to explore the assumptions and costs of SB-188 in more detail and ensure that any decision made is an informed one.

REPORT KEY FINDINGS

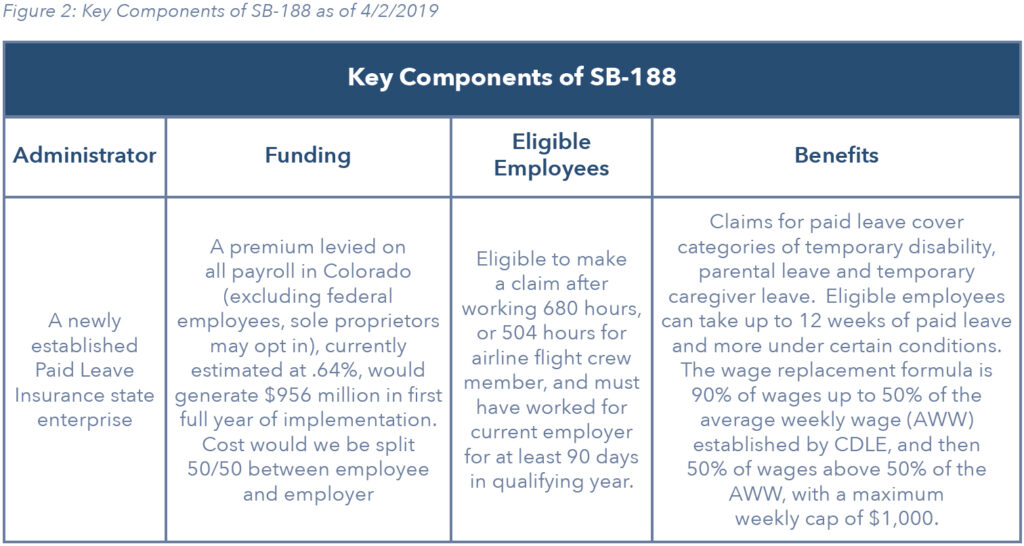

- Colorado Senate Bill 188 – SB-188 proposes to establish a new state enterprise that would administer a paid leave insurance program. A new premium would be imposed on all Colorado payroll, excluding federal workers. Employers and employees would share the cost 50/50. The revenue generated by the premium would be used to administer the new enterprise and to pay paid leave benefit claims.

- Benefits would allow for eligible employees to take up to 12 to 16 weeks off work for qualifying leave, covering temporary disability, parental, and temporary caregiver leave.

- Wage replacement during leave is based on a formula; covers 90% of wages up to 50% of the average weekly wage established by the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, and then 50% of wages above 50% of the AWW, up to $1,000 per week.

- Uncertain financial assumptions – The estimated cost of SB-188 depends on several assumptions. Arguably the most impactful of those assumptions is the rate of utilization. The fiscal note attached to SB-188 assumes a utilization rate of 3.5%, which is lower than 2 of the 3 states that have a history of administering paid leave programs, even though SB-188 would create a more generous wage replacement benefit structure.

- If the utilization rate in Colorado were to jump to 7%, which would still be 6% lower than the utilization rate Rhode Island, the revenue needed to fund the program would double to $1.9 billion. The payroll premium needed to fund the program would also double to nearly 1.3%.

- With the adoption of an amendment to SB-188 to cap the premium rate at .99%, there is significant risk that the revenue from the premium payments will not be enough to fund the program. If annual costs permanently increase to beyond where claims can be paid with a .99% premium, the agency would not be able to ever pay off the perpetual issuance of revenue bonds to cover claims, and as an enterprise the agency would be limited in how much general fund money it could receive.

- As an insurance program that requires cash to be paid on short notice, any spike in claims could cause disruptions and sporadic increases in premium rates.

- Operational disruptions – Aside from the financial impacts, many employers are concerned about the potential disruptive impacts to operations as employees take more and longer leave from work. Existing survey research and reviews of aggregate industry level data in California suggest that employers don’t report dissatisfaction with the program and don’t face higher turnover costs. However, in California, employees pay 100% of the premiums and the maximum allowable family related leave was much shorter than proposed in SB-188.

- Economic impact – Even without the potential for escalating costs and disruptions to company operations, the economic impacts of the current estimated costs could be significant. While the benefits would largely be spent in the local economy, the currently estimated cost increase to businesses of more than $478 million would represent an effective tax increase relative to the state’s existing corporate income tax of over 70%.

- A report by the Research Foundation at the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), using the REMI PI+ model, quantified the economic impact that a paid leave program with similar benefits and premium costs split 50/50 between employer and employee would have on the Colorado economy. A summary of their findings includes:

- Direct costs to workers and businesses of $2.6 billion by 2029

- The loss of 13,900 jobs by 2029

- An economic loss of $1.5 billion GDP by 2029

- A loss in real disposable income of $1.8 billion by 2029

- A report by the Research Foundation at the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), using the REMI PI+ model, quantified the economic impact that a paid leave program with similar benefits and premium costs split 50/50 between employer and employee would have on the Colorado economy. A summary of their findings includes:

- Lessons from existing state programs – Existing state benefit programs that rely on financial assumptions for adequate funding don’t always live up to expectations.

- The unfunded liability of PERA, the state pension fund for public employees in Colorado, has climbed significantly due in large part to investment returns lower than assumed and an increasing cost of retirement benefits. The unfunded liability persists even though lawmakers have approved four separate financial rescues of PERA since 2000. Despite the most recent effort in 2018, recent poor investment returns are likely to trigger additional cost increases for public employers, public employees and ultimately taxpayers.

- During periods of increased unemployment, the solvency of the state’s unemployment insurance fund has suffered, and a series of surcharges were imposed on employers on top of the base rate they already paid. Those surcharges were in effect from 2004 to 2012. In 2009, while $125 million was collected from the base rate, an additional $215 million had to be collected in surcharges from employers, to keep the fund solvent. Higher costs to employers above the base rate have persisted since the end of the last recession and even through periods of record low unemployment in Colorado.

- Legislators should consider ways that account for the financial risk that don’t just increase costs to businesses and individuals, but that reform the benefits to remain inline with anticipated costs.

- Outstanding research areas and paths forward – Given the outstanding questions on the need for a state-run paid leave program, the economic impacts and the potential for escalating costs, there could be several alternative paths forward:

- There is no current research that clearly points out existing gaps in paid leave insurance or compensation in Colorado and what limiting factors exist for private options.

- Take the time to study the pros and cons of such a program and develop a policy that would have minimal interruption of the private sector and is more targeted to address any market failures or resolve interfering regulations that may exist.

- Consider alternative policy designs that allow for more employer and employee choice. Legislation has previously been offered that would provide larger financial incentives for employees and employers to invest and save in individual paid leave savings accounts.

- Rather than litigate the extent to which the funding of SB-188 is a tax or not, consider the possibility of taking the approval of a social insurance program funded by employees and employers directly to the voters as intended by the state’s constitution.

BACKGROUND: WHAT IS SENATE BILL 188?

To allow for employees to take time off work, two broad types of policy exist. First, is the protection for the employee that they will be able to return to their same job after taking leave, and second, is partial income replacement for the employee during the time they are taking qualifying leave. Different forms of these policies are adopted by businesses and by governments across the country but cover three broad types of leave:

- Temporary disability

- Parental leave

- Temporary caregiver

The 1993 Federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) establishes a consistent law across the country that addresses employee protections for unpaid leave. In 2013, Colorado adopted a new law that sought to expand upon some aspects of the federal FMLA, primarily extending the definition of family members to include civil unions and domestic partnerships. Many public and private employers have supplemental policies for unpaid leave that cover a broader range of benefits and employees than covered under FMLA.

Federally, there is no program that provides paid leave for time away from work. That leaves the option on whether to provide paid leave to individual companies, who do so through a combination of private insurance and self-financing. Until just the past two years, 5 states including California, New York, Rhode Island, New Jersey and Rhode Island have had statutory temporary disability paid leave insurance programs and 3 states, California, Rhode Island and New Jersey have had paid leave programs that also cover parental and caregiver leave. Recently, Washington state, New York and Washington, D.C. have adopted paid leave programs that cover leave to care for family but these programs have either not begun or don’t yet have comprehensive reporting on them.

Senate Bill 188 would establish a new Colorado state enterprise to administer an insurance program that offsets workers lost wages when they take qualifying time off work. Rather than rely on personal savings, an existing employer plan or some other source of income replacement that a worker would use as financial support when taking time away from work, Senate Bill 188 would create a state operated insurance program than would be available to between 85% and 90% of all Colorado workers. The program is funded by a premium on the wages of all workers, 50% of which is paid by the employee and 50% which is paid by the employer.

Eligible workers would file claims to the insurance administration to receive direct payments that are to be used to replace lost wages as they take time off work. The reasons for taking leave, span several broad areas including temporary disability, medical leave, parental leave, and leave to be a temporary caregiver. The level of wage replacement someone would receive is on a sliding scale based on the percentage of their average weekly wage and is capped at $1,000 per week. Most individuals can qualify for up to 12 weeks of leave, with some circumstances that would allow for an additional two weeks, every year that they meet the qualifying requirements.

The newly established enterprise would be responsible for verifying and paying claims along with setting the appropriate premium rates to ensure the fund was solvent. For the first two full years of the program, 2023 and 2024, the director would be required to set premium rates sufficient to raise enough revenue to cover 150% of the anticipated benefits paid in the following year plus 100% of the administrative costs. For 2025 and each following year, the director would need to set the rate so that collections would be between 125% and 150% of the next year’s claims plus 100% of administrative costs, after accounting for any rollover revenue. Per an amendment adopted in committee, the premium would be capped at .99% of wages. The initial fiscal note estimated the premium at the start of the program to be .64% of wages.

The initial fiscal note, prepared by Colorado Legislative Council Staff, summarizes the bill and estimates the fiscal impacts to the state and local governments to the extent they deem reasonable. As several consequential amendments were passed in committee, it should be the case that some of the fiscal estimates will change upon the preparation of a new fiscal note as the legislative debate continues. This report focuses on the financial and economic impacts of SB- 188 and emphasizes the most crucial elements that not only impact the estimated costs, but more importantly, how those impacts may cause significant variation from current expectations.

Advocates for a state-run paid leave program view this program as essential to establishing a basic amount of paid leave to every worker in Colorado. Given that not every company offers paid leave benefits, they argue this would give every Coloradan the opportunity to take time off work to care for themselves or a family member. They cite the hardships that confront certain individuals as they make decisions about whether to forego income or jeopardize a job, in order to bond with a newborn or support an ailing parent. The expectation is that this bill would improve worker productivity, by keeping parents and other workers connected to the labor force upon returning from leave.

Opponents argue that a one-size fits all state mandated program does not appropriately account for the unique circumstances of each company or employee. They argue that the direct costs and indirect costs associated with business disruptions would be significant and damage the business climate in Colorado. Many who provided testimony, spoke to concerns for how this mandate would interact with their ability to continue to fund existing paid leave benefits, or other benefits, that may be more generous than what is offered in SB-188. Some public sector employers are concerned with the bill as an unfunded mandate that will crowd other government spending priorities.

SB-188 ASSUMPTIONS VS. EXPERIENCE OF OTHER STATES

Companies across Colorado continually address which types of compensation-based benefits are best for their company and employees. Along with a set wage structure, companies can also choose to offer any combination of health care, dental, disability, vacation, personal time, retirement, parental leave or other leave, paid or unpaid. Undoubtedly, employers that recognize the value of their employees, strive to find cost effective solutions to address the unique compensation needs of their employees and their business. Many employers have chosen to offer various forms of each of these benefits. A recent trend across the United States has been to further extend paid family leave to allow for employees to care for newborn children or family in need of more intensive care.

There are benefits of paid leave for many employers, which is why many already choose to offer such programs. When people choose to take time away from work to attend to a sick family member, or care for and adjust to life to with a newborn, having a stream of income can provide peace of mind and support, allowing for time to be with loved ones.

What is unclear is the degree to which establishing one of the most generous state-run paid leave programs in the country, is necessary and would not suffer the same fate as of other state benefit programs that have seen steady cost increases. While advocates have cited that 88% of Colorado workers do not have access to paid leave, it is unclear where that figure comes from. Even less clear is exactly what level of coverage that figure is referring to. If evidence-based policy is to be the standard, it is challenging to even begin debating this topic, without clearly understanding the current scope of the problem that is trying to be solved.

It is also unclear if any market failures might exist and support the argument that the private insurance market is not capable of offering an equally or more competitive insurance product. Forty-eight states have deemed auto insurance to be so important that having an auto insurance policy is required to drive a vehicle. But rather than operate the insurance program as a state organization, through some form of auto insurance premiums, it remains a market where privately-owned companies can compete.

This analysis seeks to highlight some of the important outstanding data related questions, that would be important for policy makers to consider on whether the state is better equipped to manage a paid leave insurance program, than the millions of Coloradans and their businesses who are already making decisions about the feasibility and applicability of such a program to their given situation.

Even as the basis of SB-188 is to serve a social need, the sponsors recognize it must be maintained by a financially solvent agency. This is the reason why the benefit claims would primarily be paid by a premium collected from all payroll in the state. Using actuarial methods to model the proposed program, the Colorado Legislative Council fiscal analyst has arrived at the initial financial parameters. A .64% payroll premium would be sufficient to pay for the $956 million in the first full year of claims and administrative costs. Underlying those figures are several key assumptions.

- Wage growth – Influences both how much revenue will be collected and what the cost of wage replacement will be during leave.

- Average length of leave – This would be estimated across the different types of leave claims. i.e. Parental, caregiver, temporary disability.

- Utilization rate – This represents the percent of employees who will use the benefit and take leave in any given year.

The largest uncertainty surrounding the estimated costs of SB-188 lie around the utilization rate. The current fiscal note assumes a rate of just 3.5%. Three states have had a history of state-run paid leave programs that vary in their level of benefits but are all funded 100% by employees. The reported utilization rates associated with their benefits range from 3.2% in New Jersey1 to 4.8% in California to 13% in Rhode Island. This is using a utilization rate that compares the number of claims against the number of eligible employees, which is the comparable ratio used in the initial fiscal note for SB-188. The utilization rate is seemingly influenced by just how much of a worker’s income is replaced during their period of leave. Each of these states had lower wage replacement ratios at the time of the reported claims data, relative to SB-188. Therefore, it is reasonable to question what would happen if the utilization rate were to increase.

The costs of benefit payments and the needed payroll premium scale linearly with an increase in utilization. Therefore, if the utilization rate were to be 7%, the needed premium to keep the program solvent would actually jump to over 1.25% of payroll and the total revenue collection would increase to roughly $1.9 billion. Given the employer share is 50%, that would equal a roughly $950 million increase. In 2018 the total revenue collected from the Colorado corporate income tax was just over $660 million. Therefore, with a utilization rate of between 3.5% and just 7%, the premium on employers would represent an effective tax increase relative to the corporate income tax of 70% to over 140%.

An amendment that passed in the Senate Business, Labor and Technology committee imposed a ceiling on the premium rate that the new paid leave insurance enterprise could charge of .99%. Somewhere in the middle of a 3.5% and 7% utilization rate, a .99% premium would not be enough to keep the program solvent. At that point it is uncertain how the agency would be able to proceed. It is not clear if it would have the authority to impose a surcharge to make up the difference. As an enterprise, the agency would be allowed to receive less than 10% of annual revenue as established by TABOR. It would have revenue bonding authority, but it would be impossible for the financing of the bonds to ever be paid off if the costs remained consistently higher than what the .99% premium would allow.

DETERMINING THE COST OF SB-188

Utilization Rate

To understand the financial implications of a paid family leave program operated by the state of Colorado, it is important to understand the different moving parts that influence the commitment being debated. The most important assumption is around the rate at which claims will be filed. This assumption determines the expected amount of expenditure needed, and therefore, the rate of the premium required to keep the program solvent. This is the same calculation that every insurance company makes when determining how to price a policy. It is the reason life insurance companies ask applicants about their health history, and the reason car insurance companies change their rates depending on a driver’s accident record.

Along with the utilization rate there are other important factors that are part of the financial estimates:

- Average length of benefit taken

- Wage growth as it impacts both the collections from the premium and the cost of claims

- The distribution and average wage of beneficiaries

Share of workforce covered

The current fiscal note attached to Senate Bill 188 assumes a 3.5% utilization rate.2 While not clearly defined in the fiscal note, the figure seems to be the estimated share of claimants relative to the total number of employees in Colorado. This is an important distinction from the share of employees eligible for leave, particularly when comparing the experience of other states. For example, in Rhode Island the combined utilization rate for their Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) and their Temporary Care Insurance (TCI), both of which reflect the types of benefits covered in SB-188, is 13.7% of employees who pay into their TDI program.3 However, by taking the utilization rate as a share of claims compared to all jobs in the state, the rate drops to 11%, given covered employees equal roughly 80% of total employment. This is because there is still a threshold that employees must meet to be eligible for benefits, but also because employers in Rhode Island have the option to offer paid leave benefits that are equal to or greater than the state benefits, and then not pay into the state insurance pool. In California, the share of jobs that are eligible for paid leave is roughly 99% and therefore using the two different methods to estimate a utilization rate, it comes out to 4.8% of eligible employment and 4.7% of all employment.4

While the initial fiscal note attached to SB-188 assumed 3.5% of all Colorado jobs would take some form of paid leave under the proposed program, it indicated that the range of utilization could be between 1.2% and 10%. A recent study by faculty at the University of Denver5 on a potential paid leave program in Colorado that very closely resembles SB-188 assumed a utilization rate of 5%. While the exact reason for the varying utilization rates in each state is a function of the structure of the benefit, the number of participating employees and the demographics of the workforce, the basic premise stands. The observed range is quite large, and potentially much higher than the rate used in the current fiscal note.

Under the current assumptions, upon full implementation, the initial fiscal note estimated a single year cost of $956,486,678, 88% of which would be paid back out through claims. This requires an estimated .64% premium on nearly all payroll in Colorado to fund. That cost would be split equally between employees and employers and would come to $384 annually for a worker making $60,000 a year.

Amount of wage replacement

A large determinant of the utilization of a paid leave program is based on what percentage of wages are being replaced by the insurance benefit. Both New Jersey and California recently increased the average share of wages that are replaced in their program, yet the previous utilization rates cited in figure 3 were from the original level of wage replacement formulas cited in figure 2. Prior to 2019 changes, in New Jersey workers could receive a paid leave benefit up to 66% of their wages, capped at $633 per week. Prior to 2018 changes, workers in California could receive a paid leave benefit equal to 55% of their wages capped at $1,173 per week. Under SB-188, the wage replacement formula would cover 90% of wages at or below the average weekly wage (AWW) set by CDLE for workers compensation claims, and 50% of wages above the AWW. It would also cap the claim at $1,000 per week. Therefore, for the worker making the average weekly wage in 2019, set at $1,085.55, they would have 70% of their wages replaced under proposed program. A worker making 20% less than the AWW would have 75% of their wages replaced and a worker making 150% of the AWW would have 65% of their wages replaced. According to a recent DU study, 56% of workers would be eligible to have over 80% of their wages replaced.

Given the wage replacement rate in SB-188 is seemingly higher than other states with claims history, it is plausible that the utilization rate could be significantly higher. At a 7% utilization rate, the cost would presumably double to $1.69B along with the premium rate to around 1.28%. At a 10.5% utilization rate, still 3% lower than the experience in Rhode Island, the annual cost would triple to $2.5B along with a premium rate at nearly 2% of pay.

The framework established in the bill allows for the appointed director of this new Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Enterprise to change premium rates as needed to fund the next year of claims. Further, for the first two years they are required to set the premium rate so that the paid leave insurance enterprise will have enough revenue to cover 150% of the following year’s expected claims plus 100% of administrative costs. After the first two years that requirement drops to setting a rate that will collect between 125% and 150% of the following year’s claims plus 100% of administrative costs accounting for rollover reserves.

However, following the first committee hearing, an amendment was accepted that would cap the allowable premium at .99% of wages. Given the uncertainty in the utilization, and the potential for escalating rates, one can quickly see how with slight fluctuations that deviate from these initial assumptions, the premium cap set in statute would not be enough to fund the program. At that point, it seems an open-ended question as to how the program would be funded in the event the ongoing cost would be higher than .99% of wages.

Statewide Economic Impacts

In 2018, the total amount of revenue collected from the corporate income tax was $660 million.6 With the estimate from the initial fiscal note, the $478,243,339 increase in costs on employers would represent an effective cost increase to businesses of over 70%. At a 7% utilization rate, the effective increase in costs would be 140% of current corporate income tax revenue. As the paid leave insurance premium is applied to the cost of labor, and the corporate income tax is applied on earnings, it certainly will not be the case that this percentage increase in costs is the same for every employer. Companies that have low profits but high labor costs, will see relatively larger impacts than companies with higher taxable income relative to labor costs.

Given businesses operate on a fixed budget, those cost increases have to come from somewhere. It may come at the expense of lower profits to shareholders, making investing in Colorado less attractive. It could come from lowering existing benefits paid to workers such as through vacation time, personal time or in health plans. It could also come from lowering labor costs through hiring fewer workers or reducing wages.

Macroeconomic impacts

In a study released late January 2019 by the research foundation at the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), using the REMI PI+ model, found that a state mandated paid leave program, with costs split 50/50 between employer and employee would lower employment by nearly 14,000 jobs and over a $1.8 billion decline in real disposable income by 2029.

The analysis includes direct costs that are very similar to the estimated costs in the initial fiscal note. The economic impacts represent the net effect from the increase in direct costs to employees and employers to fund the program, and the direct benefits accrued to program recipients who have their incomes partially replaced during the period of the leave. The analysis is conservative in that it doesn’t include any administrative costs, and cycles 100% of the premium revenue back into the hands of recipients. The current fiscal note for SB-188 estimates that the cost to administer the program will be just above $17.4 million in the first full year of implementation between the new agency under the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment and the collection services at the Department of Revenue.

Threat to small business

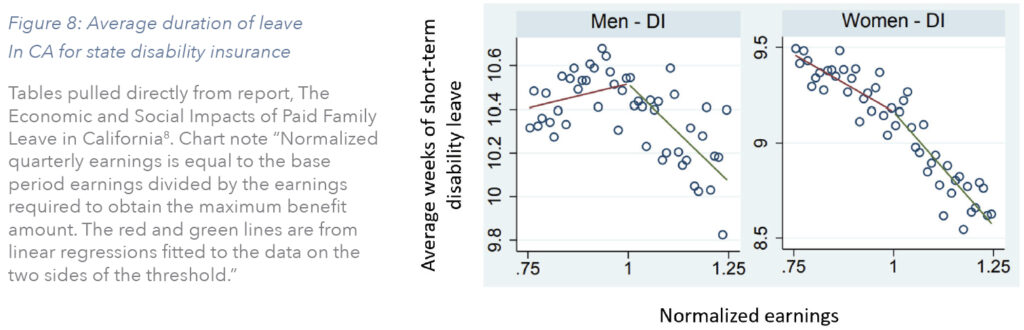

Along with the fiscal and economic impacts, a higher utilization rate has other implications for operational impacts on businesses, particularly small businesses, as a larger share of workers take more paid leave time away from work. Previous research into this issue in California concluded there were limited to no impacts on businesses in terms of turnover or productivity slumps. The research found that on aggregate, turnover rates by industry had declined over the length of the policy. In both California and Rhode Island7, survey results have shown a majority of businesses favored their existing paid leave programs. A significant difference to note, however, is that employers are not required to pay part of the premium, and the allowable time-off for paid leave for parental and caregiver leave was lower than SB-188. And while the benefit structure allowed for up to 52-weeks for paid leave for temporary disability, according to 2016 research, the average short-term disability leave duration was less than 11 weeks for both men and women as shown in figure 8.

Learning from Colorado’s Past

Lessons from PERA; When assumptions don’t match reality

The state public employee’s retirement association, or PERA, provides eligible Colorado state and local government employees with a retirement pension. As a defined benefit plan, PERA is required to pay its members a specific amount during the full term of an individual’s retirement, after collecting a set amount from each paycheck during each member’s working years. This is different from a defined contribution plan, where the contributions during working years, plus the investment returns, have to equal the sum of the individual’s retirement payments. Similar to the financial cost estimates underlying Senate Bill 188, the projections for how much each PERA member and agency need to contribute is based on certain assumptions made by the actuaries. However, the contribution amounts are set by statute in the legislature, regardless of what the actuaries have said is needed. For over 15 years, the funding status of PERA has been poor, and only getting worse. This was a direct result of reality not living up the actuarial assumptions. The actual average rate of return since 2001 has been below the target rate of return, and PERA had changed their mortality tables by increasing life expectancy for its members, both of which hurt the financial position of the fund. As a result, during the 2018 legislative session, the legislature decided to appropriate $225 million annually directly from the state’s general fund to payoff the unfunded liability over the next 30 years. This was on top of an additional increase in contributions by employees and employers and cuts to benefits. Following three prior efforts to stabilize Colorado’s pension fund since 2000, the PERA employer or taxpayer contribution rate has now escalated to over 20% of pay, with a majority of that money used to pay for the higher costs of past service, or just paying down the unfunded liability. And with the poor investment returns in 2018, it is likely that automatic adjustments will take effect that only further increase contribution rates and lower benefit increases for next year.

Fluctuating costs for unemployment insurance

Following the 2001 recession and 2008 financial crisis, the state’s unemployment insurance program faced insolvency. It triggered a set of surcharge increases that raised rates on employers just as the economy was slowing and employment was declining. This was by design, as the base rate of between 0% and 5.4% was not enough to cover claims. The surcharges that kicked in more than doubled the cost to between .22% and 11.02% of pay at times. For 13 years, between 2004 and 2017, there were additional payments required of Colorado employers beyond the base rate. In 2009, while the base rate, that under normal circumstances would be the only payment amount, collected $120 million, the combination of two additional surcharges collected $216 million. 2008 was a similar case in that more revenue was collected from surcharges than from the base rate.9

Biggest Outstanding Questions and a Path Forward

Evidence based policy has to the be the standard by which critical fiscal and social issues are debated. The benefits for certain employers and employees of paid leave are not in question. But just the benefits alone are not justification for the implementation of a new billion-dollar state enterprise, given the outstanding questions and uncertain costs. What is unknown is the extent to which this is a systemic problem that the private sector is unable to solve, or if it is a matter of different choices made by individuals and companies that fit their own circumstances.

What does paid family leave look like in Colorado as a starting point?

There are certainly challenges around obtaining data on coverage from multiple private insurers. But while the proponents of this measure have stated that 88% of Colorado employees don’t have access to paid leave, it is unclear where that claim comes from, and therefore it is unclear exactly what type of coverage is being referred to. If it is referring to paid leave beyond vacation time or personal time that would imply one thing. If it is referring to paid leave beyond vacation time, personal time and 100% wage replacement for 12 weeks that would imply something entirely different. Knowing what the landscape of existing coverage looks like should be a starting point for any discussion on whether public policy is necessary in the first place.

What is proper oversight of a new insurance enterprise?

The Colorado Division of Insurance is tasked with regulating the insurance industry in Colorado. A reasonable question seems to be around why the Division of Insurance would not have oversight over a new state insurance agency the same way it does private industry. Given private businesses have to comply with all the regulations under the DOI, it would seem reasonable to require a similar standard of any new paid leave enterprise.

Why can’t private insurance or private savings plans reach those that don’t currently offer or have paid leave benefits?

Upon knowing where coverage exists in the state, it would then be easier to identify the exact reasons why certain individuals don’t have coverage, or why certain employers don’t offer coverage. While some choose to use savings to cover for lost wages, others prefer to have an insurance plan to replace all or some of lost wages, while others have agreements with their employers to have their wages replaced even if they aren’t working. Given SB-188 effectively establishes a state-run insurance company, it would be important to know exactly why the state can purportedly offer a more affordable plan than the private sector. Earlier in the 2019 legislative session, there was a bill introduced that would have given preferential tax treatment for savings accounts that were contributed to by workers and for employers that offered paid leave. Opponents argued that lower income workers would never be able to save an adequate amount of money, but it is unclear why a private insurance option would be out of reach.

Is taxpayer-funded leave a right? Why not take the question directly to voters?

Putting aside the arguments over the need for a state-run paid leave program, and the cost assumptions underlying SB-188, it is important to step back and consider the way this legislation is being pursued. By establishing a state enterprise, SB-188 would establish a TABOR-exempt enterprise with authority to raise revenue directly on the transaction of labor between an employer and an employee. Whether the courts decide these payroll premiums constitute a tax or not, asking voters to decide the issue would certainly be consistent with the spirit of the Colorado Constitution. Supporters and opponents of SB-188 may disagree about the need for this legislation and how much it will likely cost, but this much is clear: The payroll premiums needed to fund a state-run paid leave program will impose a cost increase directly on the work of millions of Coloradans. For this reason alone, debating this proposal fully with the state’s voters is an idea worthy of consideration.

REFERENCES:

- New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development Office of Research and Information, “Annual Report for 2017 Family Leave Insurance and Temporary Disability Insurance Programs,” 2018.

- C. Pramuk, “Fiscal Note: FAMLI Family Medical Leave Insurance Program”.

- Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, “2017 Annual Report,” 2018.

- Employment Development Department, State of California, “October 2018 Disability Insurance (DI) Fund Forecast,” 2018.

- J.C. Greenfield, N. Reichman, P. C. Cole and H. Gagliani, “Projected Economic Impacts of Paid Family Leave in Colorado,” 2019.

- Colorado Department of Revenue, “2018 Annual Report,” 2018.

- J. Waldfogel, “Paid family and medical leave legislation: Evidence from employers,” 2018.

- M. R.-S. Kelly Bedard, “The Economic and Social Impacts of Paid Family Leave in California; Report for the California Employment Development Department,” 2016.

- Colorado Office of State Auditor, “Evaluation of the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Department of Labor and Employment,” 2010.