Check out the full systems map HERE.

About the Authors

Each author’s contributing section is identified in the table of contents. As a joint project between CU Denver and CSI, with many contributing scholars, any individual’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of either organization.

Dr. Arianne Collopy is a Design Science researcher and systems innovation design lead at the University of Colorado Denver and the Inworks Innovation Initiative-Comcast Media and Technology Center, the home of a design innovation team that brings together students from across campus to create impact through design. Dr. Collopy completed her PhD in Design Science at the University of Michigan and has experience as a policy analysis associate at the RAND Corporation. Her work applies interdisciplinary methods to the study and practice of systems design and product design for diverse application areas.

Kelsie Faulds is Inworks’ Program Manager. With expertise in complex systems and human-centered design, she focuses on empowering interdisciplinary teams of innovators as they solve hard human problems, particularly at the intersection of policy and technology.

Dan Griner is the Director of Design, Innovation and Strategy for University of Colorado Denver Inworks Innovation Initiative. He brings to that role 25 years of experience in design leadership in a variety of fields including product design, medical products, zoo environments, playgrounds, digital products, and innovation. He is a member of the board of directors of Make4Covid, a crisis response non-profit. He has worked in public education (K-12) and Design education in the USA, South Korea, and India. This varied experience has helped him communicate abstract ideas to diverse audiences and adapting processes to fit the needs of differentiated users and take on unique challenges.

Peter LiFari is a CSI 2021 Terry J. Stevinson Fellow and co-authored the July report, “From Conflict to Compassion: A Colorado Housing Development Blueprint for Transformational Change.” Peter is the Executive Director of Maiker Housing Partners. Maiker, an owner, operator, and developer of affordable housing communities in Adams County, CO, collaborates with other Housing Authorities to collectively work toward the overarching mission of the industry to create attainable and sustainable housing and communities for vulnerable families and individuals.

Lili Valis graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder in 2019 with a B.A. in Political Science and a minor in Business Administration. She moved to Washington, D.C. after graduation where she worked in business development. After coming back to Denver, she joined Common Sense Institute as a Research Analyst before she will join the United States Air Force through the Officer Training program in September 2021.

Brenda Dickhoner, Ph.D. has spent the last decade working in education policy at the national and state level. Most recently, at the Colorado Department of Education, she developed and implemented policies to ensure all students have access to a high-quality education. Prior to CDE, Brenda served as an expert for the Colorado Department of Higher Education on research and policy related to college access and success. Brenda earned a Ph.D. in Public Policy at the University of Colorado Denver School of Public Affairs and studied political science as an undergraduate at Duke University.

Special Thanks

We would like to thank first and foremost, the many individuals who are working to end homelessness every day. We also would like to thank all who participated in this study and who provided feedback to help us more accurately describe to our community what challenges you deal with in your daily work.

Lidet Birhanu, Marie Evans, Erin Christon, Stephanie Chesler, and Dr. Kristin Wood for their contributions to community outreach, interviews, and background data collection that informed this report.

About Inworks-CMTC

Inworks is an innovation initiative of the University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical Campus. A home for creators, thinkers, designers, and makers, we’re a collaborative community of learners and leaders committed to solving humanity’s most pressing problems. In our two state-of-the-art prototyping labs, we draw on expertise from many disciplines to create unique solutions to real-world challenges. At Inworks, we learn and teach through making, but we don’t just make things – we make them matter.

Established to be the premier scholarly hub for Design Innovation (DI) thinking, research, and practice, CU Denver’s Comcast Media and Technology Center (CMTC) uses an interdisciplinary methodology combined with academic theories for application in a practical setting. Fully embracing our expertise in cutting edge DI research and leveraging our unparalleled access to the exceptional colleges at the University of Colorado Denver, we aim to embody the spirit of collaboration by connecting across fields of study, disciplines, industry, and government. When this unique approach is applied to critical communal challenges, it results in the production of awe-inspiring solutions in engineering, art, design, and entrepreneurship.

About Common Sense Institute

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

Project Overview

Phase 1: Common Sense Institute partnered with CU Denver, the Downtown Denver Partnership, Together Denver and other local associations and business leaders to conduct an economic analysis of the organizations serving individuals experiencing homelessness within the city of Denver and the broader seven-county Metro Denver region. The initial phase of the project included the compilation of current resources dedicated to the various parts of the homelessness ecosystem for the purpose of understanding the economic footprint.

Phase 2: In the second phase of the project, CSI partnered with CU Denver to engage with the local community and chart drivers and outcomes. The team captured and mapped the ways in which each organization impacts various system dynamics. In addition to providing clarity around the roles of organizations in the ecosystem, this model reveals which factors have outsized impacts and provides insights into where additional interventions and investments might address the root causes of persistent problems and accelerate the positive dynamics within the system. Through this analysis, CSI and CU Denver developed a prioritized set of recommendations with the goal of maximizing total impact.

This report represents the culmination of the work conducted during Phase 2 of this project. First, a summary of the Phase 1 findings is presented, followed by several parts: 1) systems mapping analysis and recommendations; 2) case studies; and 3) a brief on homelessness and housing affordability.

Phase I Economic Analysis Summary

Authors: Lili Valis and Brenda Dickhoner

The Phase I report, The Economic Footprint of Homelessness in Metro Denver, found that nearly half a billion dollars is spent annually on shelters, supportive services, health care and public assistance for individuals experiencing homelessness in the Metro Denver area. Within the city and county of Denver the figure approaches $447 million. These estimates are likely undercounting the full breadth of spending on this issue. The figures only include financial information that was available and do not capture the full array of charitable organizations, religious organizations, public agencies or health care and emergency responders that are dedicated to serving people experiencing homelessness. The analysis of annual expenditures includes only a partial list of municipal agencies engaged on this issue within Denver, Boulder and Aurora, and does not include any city or county agencies in other areas of Metro Denver. While Denver Health costs ($176 million) are included, other regional and local hospital and health care costs are not included.

These estimates begin to shed light on the systemwide resources available to resolving homelessness. There is a growing demand on public resources and increasing scrutiny on public policy. An understanding of the existing resources – fiscal, human, and otherwise – can help launch a conversation about how the Metro Denver region can better connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness with stable housing and wraparound support. As the number of people experiencing homelessness continues to rise and as communities recover from COVID-19, now is a critical time to assess the ecosystem.

Phase I Economic Footprint Summary

- The 2020 Point in Time (PIT) count, which provides a snapshot of the population experiencing homelessness in the region, counted 6,104 people experiencing homelessness on Jan. 27, 2020 in Metro Denver (covering the counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Broomfield, Denver, Douglas and Jefferson). 4,171 of those individuals were living within the boundaries of the city and county of Denver, representing 68% of the region total.[i]

- Due to COVID-19, the 2021 PIT unsheltered count was not conducted, leaving an unclear picture of how the pandemic has affected the homeless population overall. However, the 2021 PIT count of people staying at emergency shelters revealed a 40 percent increase over the prior year.

- Within the Metro Denver region, at least $481.2 million is spent annually on shelters, services, emergency response and healthcare for individuals experiencing homelessness.

- Out of the total estimate of $481.2 million, approximately $434 million is spent within the City of Denver, while approximately $15.9 million is spent with the City of Boulder and approximately $7.8 million is spent within the City of Aurora.

- For a population ranging from 4,171 to 10,428, these expenditures equate to a range of $41,679 per person to $104,201 per individual experiencing homelessness in the City of Denver.

- In comparison, the per-pupil spending in K-12 schools in Denver Public Schools in 2019 was $19,202 for a total school population of 87,644.

- The estimated $481.2 million in expenditures likely capture some revenues flowing from the 2020 Cares Act to organizations in the Metro Denver region, given the report focused on FY 2020 expenditures from charitable organizations. The $481.2 million amount, however, does not include COVID-19 federal stimulus funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which was enacted in March 2021 and provided $29.4 million for the HOME Investment Partnerships Program.

- Additionally, the state has proposed to use $550 million of the $3.8 billion in state funds received from ARPA for the purpose of affordable housing.[ii] It is expected that some portion of this will go towards supporting people experiencing homelessness. Colorado has also put state funds toward the Colorado Rescue Plan, under which $15 million has been allocated to purchasing hotel rooms for unhoused individuals and $13 million is allocated for affordable housing project incentives.[iii]

Additional Impacts of Homelessness

The Phase I economic analysis of homelessness considered the direct expenditures by charitable organizations and government agencies to provide services and support to people experiencing homelessness. The homelessness crisis also impacts surrounding aspects of the economy that are less easily quantified. For example, tourism can be impacted if cities are perceived to be unsafe, local businesses may lose revenue if encampments or individuals experiencing homelessness are driving away customers, and water sanitation and stormwater drainage can be negatively impacted by growing numbers of encampments that do not have access to bathroom facilities.

Tourism

Convention organizers are known to be selective about where they host events, and they will bypass cities with perceived safety issues and or cities that lack quality experiences. Independent travelers are also known to take into consideration the safety and cleanliness of destinations when making travel plans. Statewide tourism spending in Colorado amounted to $24.2 billion in 2019. With COVID-19, the tourism industry took a significant hit as related spending went down to $15.4 billion in 2020. Of the 2019 amount, $21.7 billion is estimated to have come from spending by visitors.

If tourism declines a mere 1%, the direct loss in tourism spending based on pre-pandemic, normal travel years would be $217 million. Using the PI+ model developed by REMI to run a simulation, that 1% drop in tourism spending would cost over 2,530 jobs statewide and over $387 million in total output. This translates to a reduction in GDP of $229 million, or -0.055% of the state’s economy.

A specific instance of homelessness affecting business tourism in Seattle provides an example of the quantifiable indirect impact to the economy. In a 2018 letter sent to the leaders of the convention and tourism organization Visit Seattle, organizers of a large national convention criticized the street atmosphere surrounding the convention center after an advanced planning team was directly accosted and witnessed open drug use and other activities which caused them to fear for their safety.[iv] As a result, organizers chose not to host the convention in Seattle. The net loss: $8.5 million in approximate expenditures to the local economy.

Local Businesses

Business owners have expressed concern about the homelessness crisis long before COVID-19.[v] The pandemic, though, wreaked havoc on businesses in Denver, and as some recover, the combination of slower foot traffic downtown and increased homeless encampments have presented an untenable situation.

In October 21, for example, a downtown business closed doors, citing the pandemic and homelessness as factors. In regards to the effect the homeless crisis has on downtown Denver, the CEO stated: “I just don’t think there’s a whole lot of effort to control or protect the businesses down there.”[vi] Another small business owner reported that their business was increasingly the focus of break ins and threats from unhoused individuals. The business owner expressed the desire for both a solution for homelessness and a way for her and her customers to feel safe.[vii]

Water

In September 2021, a group of students from University of Denver and Regis University found that only a portion of the public restrooms in Denver are open and functional, and only 30 percent of water fountains and hand washing stations work.[viii] At the same time, about a quarter of people experiencing homelessness are living on the streets without consistent access to proper restroom facilities. Not only are these conditions unsanitary for people experiencing homelessness, they also impact waterways, particularly recreational water areas.

When there is a storm, the runoff carries contaminants from streets into the stormwater drainage system, which ultimately flow into rivers, lakes, and oceans. In Denver, the South Platte River is a popular attraction for recreation, and also where much of the urban stormwater runoff ends up. The contaminants found in stormwater runoff include various chemical pollutants as well as animal and human waste, the latter of which has been tied to higher levels of E.coli in our recreational water areas. According to researchers studying pathogens in urban stormwater systems, “urban sources of human waste include homeless encampments, RV discharges, and leaky or failing septic systems.”[ix] Human waste can make its way into the rivers indirectly via stormwater runoff, or it can happen directly if there are encampments near rivers. Non-human waste such as dog waste can also contribute to higher E.coli levels in rivers through stormwater runoff.

In March 2021, Colorado health officials “declared water quality in the South Platte River as it flows through Denver highly deficient, pointing to E.coli contamination at levels up to 137 times higher than a federal safety limit.”[x]

To reduce E.coli levels, researchers recommend several strategies related to homelessness: periodic cleanup of homeless camps near streams; provision of public restrooms; police enforcement; and support for housing and services to resolve homelessness.[xi] Additionally, researchers provide an example of a grant-funded program aimed at reducing the water quality impacts of homeless encampments in San José, CA. The program employed “homeless persons living in creek encampments to remove trash and litter and to engage in peer-to-peer outreach with others living in the encampment. Participants are housed temporarily and given food vouchers, case management services, employment skills, and assistance at transitioning to permanent housing (EPA 2011).”[xii]

Conclusion

Homelessness is a crisis that has devastating effects on the over 6,000 individuals who experience it in the Metro Denver region. The crisis results in steep costs for taxpayers who are subsidizing higher spending on emergency room services, police interactions, expanding shelters and street cleanups. The homelessness crisis also touches many other areas of the economy and our society through its impacts on tourism, local businesses, and water quality, as just a few examples.

Building on this basic understanding of the economic footprint of those experiencing homelessness, Phase II of this research endeavor seeks to understand, and visualize, the ecosystem of factors that contribute to furthering homelessness as well as those factors that contribute to the prevention of homelessness or supporting those experiencing homelessness to move into stable housing. The systems map presented in the next section helps stakeholders understand and communicate how the ecosystem operates, what is working well and needs more or continued support, and where further opportunities for improvement remain.

Systems Mapping

Authors: Dr. Arianne Collopy, Kelsie Faulds, Dan Griner

Executive Summary

Homelessness is a visible outcome of a system that does not consistently work for everyone. This report is the result of efforts to understand the systemic factors that impact homelessness in the Metropolitan Denver area through a human-centered systems design lens. Human-centeredness means the data collection that informed the analysis in this report is based on conversations with individuals in the community who are in some way serving those currently experiencing homelessness and individuals who previously experienced homelessness. A systems design lens includes an emphasis on understanding how factors are connected and influence each other.

This report is intended for a general audience as a resource to better understand the interconnected system that is the ecosystem around homelessness.

In Section 2 of this report, we include our motivations and objectives in this work. Section 3 outlines our methodology for identifying community members to learn from, our conversations, and our approach to synthesizing a built understanding of the homelessness ecosystem through systems mapping. Section 4 introduces some of the larger context of our analysis. Section 5 presents the systems map through eight topic areas. Section 6 highlights some particularly impactful, unique, or innovative practices in the Metro Denver area that we find noteworthy for the change of perspective and the value that these practices bring to individuals experiencing homelessness and the providers that serve individuals experiencing homelessness. Recommendations that result from this analysis are prioritized in Section 7 along with exemplars in the community and showing how these goals are being met.

Recommended Opportunity Areas

The recommendations from this work are framed as opportunity areas to invite impactful future innovation. “How might we” questions are commonly used to invite ideation and recognize that a one-size-fits-all solution is unlikely. Detailed context and some examples of current practices are used to illustrate each recommendation in Section 7.

- Housing Access and Affordability: How might we improve pathways to affordable housing options that are equitably accessible for all residents in the Metro Denver area, regardless of what affordability looks like for each individual?

- Supporting People in Vulnerable Positions: How might we support persistent engagement by providers, consistency of service or care across providers, and build trust in providers to be able to reach and help all people before that help is critical?

- Staffing for High Quality and Consistent Care: How might we innovate staffing models and funding models of providers serving people experiencing homeless, to enhance the quality and consistency of services delivered by skilled professionals including long-term case management?

- Trust in Services and System: How might we improve the clarity, consistency, and equity of eligibility requirements for services?

- Coordination, Collaboration, and Partnerships: How might coordination and collaboration between providers and government agencies for those experiencing homelessness be enhanced, including data transparency, human-centered data collection methods, and marketing or outreach efforts to build awareness?

- Technology and Information Access: How might access to critical online or electronic information be improved for those currently or at risk of experiencing homeless without reliable or consistent technology access?

Systems Mapping: Motivation and Objectives

The ecosystem that impacts people experiencing homelessness is vast. It includes individuals, organizations, perceptions, social and societal factors, economic factors, technology, historical factors, and environmental factors. Building on a basic understanding of the economic footprint of those experiencing homelessness, this phase sought to understand, and visualize, the ecosystem of factors that contribute to furthering homelessness and that contribute to prevention of homelessness or supporting those experiencing homelessness to move past homelessness. The systems map that was created helps to understand and communicate how the ecosystem operates, what is working well and needs more or continued support, and where further opportunities remain.

Methodology & Terminology

The systems map was created by synthesizing conversations with stakeholders in the Metro Denver area, including people and organizations that provide services and support for those experiencing homelessness, people currently experiencing or who have experienced homelessness, and organizations that coordinate resources, services, and efforts in this space.

Outreach and Stakeholder Conversations

Conversations occurred in three phases. The first phase of outreach was to identify organizations to contact, which began by researching organizations in the Metro Denver area that fall into several categories of people and organizations:

- Public/Servant organizations, such as government agencies

- Job and work programs

- Substance abuse and mental health organizations

- Organizations providing food and resources

- Housing and shelter programs and services

- Hospitals and healthcare

- Advocacy groups

- Resource aggregators

- People currently or previously experiencing homelessness

Organizations that focus on support for specific populations such as families, youth, or veterans were noted. This initial research yielded 85 organizations. Organizations were prioritized for inclusion in this outreach list based on two criteria. The first criteria is organizations that span the range of types of services identified (reference the above list). The second criteria focused on seeking a broad and unique set of approaches.

Both large and small organizations were part of outreach. Both are important. Large organizations are likely to reach the most individuals, and have a high level, systemic perspective of factors that contribute to homelessness and reducing homelessness. Conversely, smaller organizations typically have a narrower scope and may reach fewer individuals, but correspondingly can share deeper insights into challenges and opportunities of individuals experiencing homelessness. Thus, this outreach was designed to build the most comprehensive view of the ecosystem around homelessness as possible from both individual, localized factors and systemic factors that influence many people and organizations.

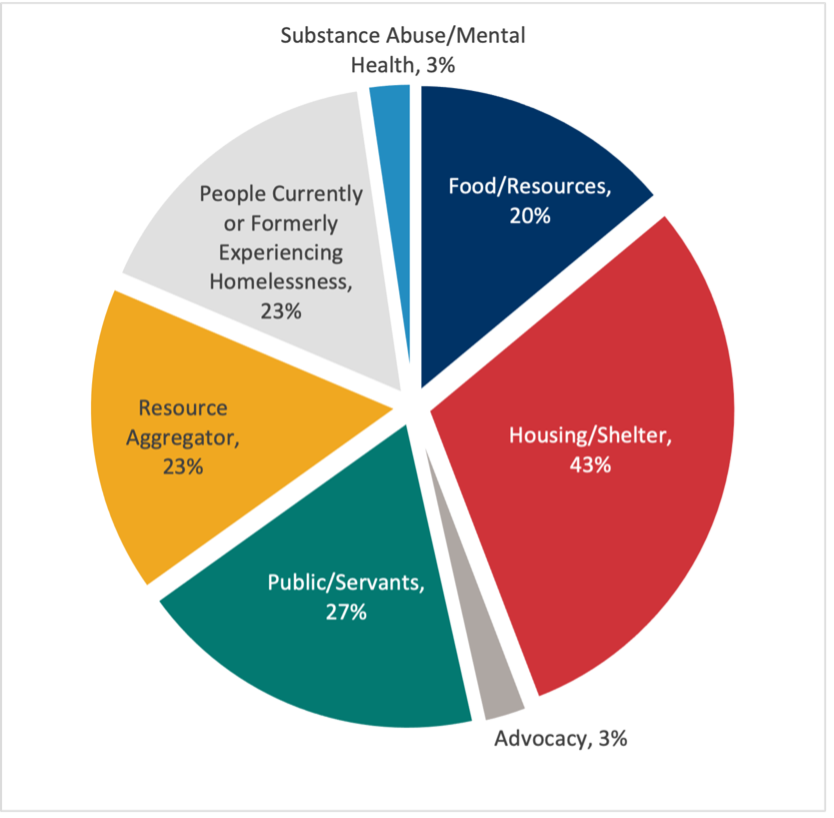

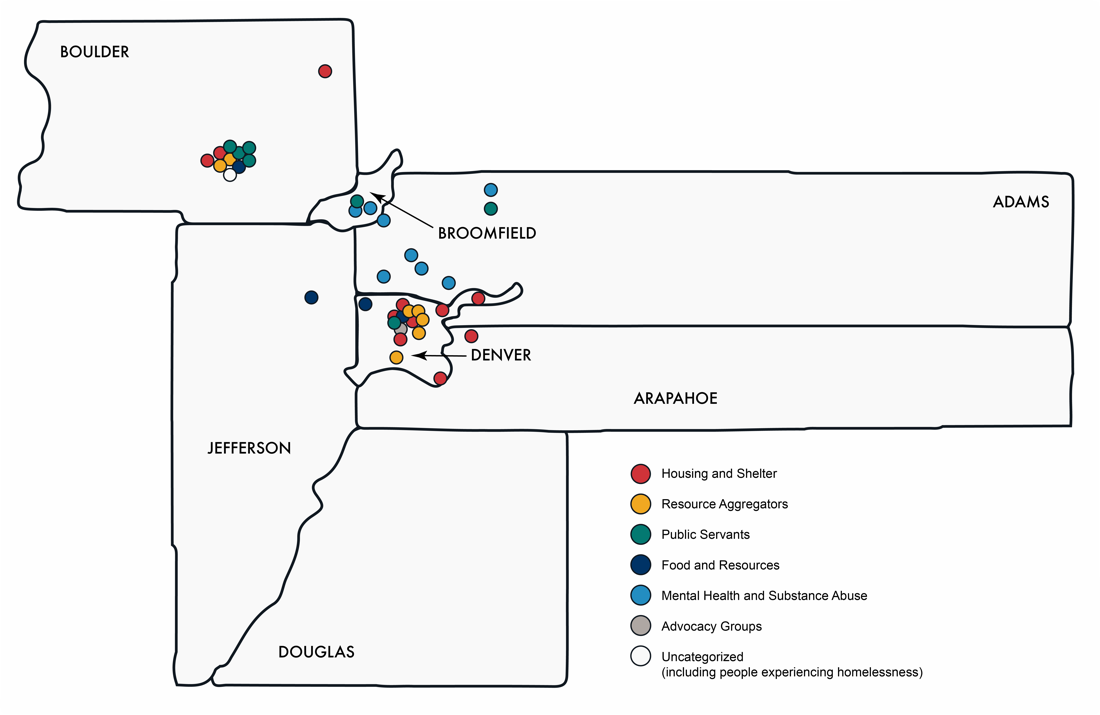

Seventy-two organizations were contacted in the second phase of our outreach. Organizations were contacted and invited to schedule a conversation. Outreach was conducted by phone, email, and by in-person visits to ensure that, for example, organizations with minimal staff to return phone calls could still opt in or out through a short in-person visit. In total, conversations were held with 30 unique organizations. The organizations that participated in conversations span each of the initial categories identified (see Figure 1), and across six of the seven counties in the Metro Denver area (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Distribution of types of organizations contacted. Total does not sum to 100% because some organizations or individuals fit multiple categories.

Figure 2: Map of stakeholder outreach. Note that there are more locations than conversations because organizations with multiple locations are shown as in all locations.

Each conversation followed a general discussion guide which prompted each organization’s representatives to share their mission, resources available to that organization or resources needed to be more effective, perceptions or reactions to their work, positive experiences and outcomes observed, and opportunities they see from the point of view of their organization and the people they serve. Questions were tailored to elicit stories and uncover the perspectives and insights of each representative, particularly regarding their understanding of why existing circumstances exist or why desired factors do not yet exist. Where possible, we used references provided in each conversation to reach out to additional community members or organizations.

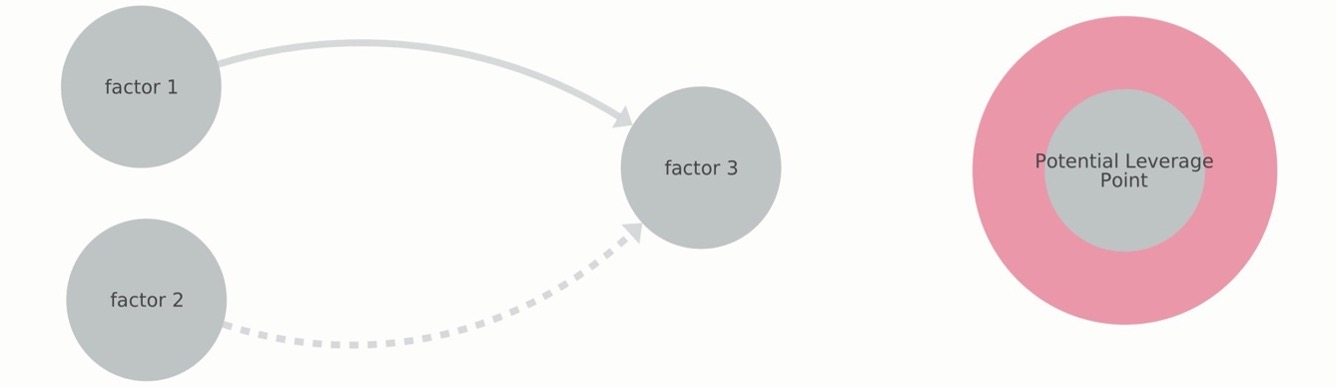

Systems Mapping

The aggregate of all conversations with organizations and individuals informed the development of a systems map, or influence diagram, which visually illustrates the connection between factors. Factors are observable states of the world, typically that can be quantified in some way. (While factors can be thought of as quantities, there are not necessarily known quantities for each factor.) Examples of factors are the number of case managers or staff working at a given point in time (people or organizations), the degree of trust in service providers (a belief or perception), and the current availability of housing (a resource quantity). Connections between factors can be positive (reinforcing influences) or negative (diminishing influences). A positive or reinforcing influence can be understood as “more of Factor A yields more of factor B”. This is denoted as a solid arrow. A negative or diminishing influence can be understood as “more of Factor A yields less of factor C”. This is denoted as a dashed arrow. A caveat is that an influence map may not be able to show every causal step between two factors.

The primary value of systems mapping is as a tool to make sense of a large space that is seen and experienced differently by many people. A systems map can identify factors that are connected and form reinforcing or diminishing cycles, only visible when the factors are considered together. A systems map can also identify individual factors that are influential, such as factors that are connected to many different parts of the system, often vulnerable points. Factors that support or detract from vulnerable factors are key to identifying opportunities for focused impact or leverage. The goals of understanding, visualizing, and identifying potential areas for focused impact in the homelessness ecosystem are therefore all supported by the creation of a systems map.

The systems map can inform a quantitative data display to augment understanding of the numbers of people experiencing homelessness and the systemic, contextual factors that shape their experience.

Validation and Limitations

As a tool to make sense of the ecosystem around homelessness, validation is a process of ensuring that the systems map is an accurate reflection of actual experiences and processes. The primary approach to validation taken was follow-up conversations with representatives in this space. Validation conversations focus on ensuring the systems map illustrates, and is representative, of their experiences in this space.

Limitations of the approach to create the systems map, and the systems map itself, are centered in the time constraint of the outreach done, and that only some community members were available in the time available. The diversity of organizations purposefully contacted aims to reduce, but cannot negate, this limitation. The systems map represents the diversity of the community members and representatives that were contacted, and is expected to reflect the broader community.

A necessary limitation of the process to create the systems map is the presence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic, stretching from early 2020 and continuing through 2021 has disrupted many ways of living and working, and the homelessness ecosystem is no different. A primary impact of the pandemic as relates to this work was the difficulty of communicating with people experiencing homelessness, and providers for those experiencing homelessness as their resources are stretched thin. This is a contextual factor that may limit the applicability of certain areas of the systems map to different points in time. However, the systems map is expected to be accurate for the current time point and can inform immediate steps to the future.

Context of Homelessness Ecosystem

The broad context surrounding the homelessness ecosystem in Denver includes factors related to finances, politics, and the Metro Denver community. The COVID-19 pandemic has been an added layer of complexity. In addition, there are existing organizational structures based in the Continuum of Care network supported by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that are integral to the ecosystem. We share some of this broad context in recognition that our understanding of this system exists in today’s context, and future opportunities are also contextualized by where we are today.

Financial Context

The financial approaches to addressing the homeless ecosystem are varied – largely because financial data in this space is not easily understood, and the numbers can include money spent for a wide variety of resources to enable different approaches. The amount of money spent in this area and the many approaches at play all speak to the complexity and difficulty of making lasting change in this space. Funding is often tied to certain outcomes or approaches based on the granting agency, making it difficult to apply funds easily to where they are most needed at any point in time. While this is an important area of focus, it was not within the scope of the System Mapping or a subject explicitly explored in our qualitative interviews. For the Economic Footprint of Homelessness report please refer to Phase 1 of this project for more info.

Classifications or typing of homelessness also impacts the financial context of the homelessness ecosystem as these classifications are often applied to service or program eligibility or prioritization guidelines. Classifications of homelessness from HUD are:

- Literally homelessness

- At imminent risk of homelessness

- Homelessness under other Federal statutes

- Fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence

Separate criteria of chronically homeless or groups such as families, youth, veterans, and elders are also used. However not all situations may be covered by the definitions written into legal code , and individuals may not be able to readily provide information to assure they fit in a given category. The guidelines for a Continuum of Care include what kinds of programs and services would be covered under a grant application, as well as restrictions and guidelines on activities such as mandatory reporting and adherence to equal opportunity protections. There is flexibility in what programs and services a Continuum of Care can provide and restrictions to only certain groups of people experiencing homelessness are possible. These choices can create additional hurdles or limits to accessing services for people who do not fit a specific classification.

Separately from the Continuum of Care, many organizations working in this space are non-profits and are in part supported by financial donations from within the community. This presents a disjointed financial picture with potentially conflicting incentives for organizations working in the same space.

Political Context

Denver and Colorado have distributed decision-making power, ranging from the community, mayoral, City, County, Metropolitan area, and the state. At the city, county and state level there are different approaches to the issues of homelessness and with a change in leadership, the previous administration’s plan can be sidelined. This changing landscape complicates how groups are able to meet the needs of those experiencing homelessness and what resources they can expect to achieve their goals. While Denver has over 80 staff dedicated to housing stability, some counties have extremely limited or no staff dedicated to the issues of homelessness and as numbers of unhoused begin to rise, they struggle to meet the needs of that community.

Homelessness features prominently in the current multi-year plans for communities across Denver. In many cities and communities whose population of individuals experiencing homeless has grown, there is a new focus and effort to engage more directly to support this population.

With the overall increase of individuals experiencing homelessness and at risk of experiencing homelessness, the most troublesome of issues within this ecosystem become more noticeable. With encampments encroaching on neighborhoods or businesses, policies quickly spring up and divert attention from the long-term solutions in favor of short-term fixes that take off some of the immediate pressure. While there is a desperate need for short-term solutions for those who are experiencing homelessness, a long-term focus helps anchor short-term solutions in a common vision of the future. Without a long-term focus that vision is hazy.

The general public is not often given a systems level understanding to help see the consequences of policies and the many types of people in danger of or currently experiencing homelessness, which can manifest as misinformed decisions by individuals or elected officials. Focus is often put on symptoms and resulting issues instead of root causes and prevention measures.

Regardless of political affiliation, homelessness affects us all and it will require a united effort to begin preventing and eradicating the problem of homelessness (not the people) from our communities.

Metro Denver Community

- Denver County’s population has grown by 21% over the last 10 years and grew by 1.6% in 2019 alone. This is a higher rate than the state of Colorado overall, which has a 15% growth 2010-2019.

- We have a housing deficit of over 175,000 homes in Colorado as of 2019.

- While being a fairly progressive state in implementing new initiatives, Colorado’s housing shortage puts us as fourth worst in the nation behind Washington D.C, Oregon, and California.

While unity across the entire Denver Metro area is challenging because of the size of the metropolitan area and the variance among communities, there are lessons to be learned through the implementation and evaluation of varied approaches and pilot programs. Evaluation of approaches and programs at a systemic level can particularly enhance understanding of how those approaches and programs may be implemented at a larger scale. Unique approaches and strengths in certain areas exist, and if promising pilot programs prove effective in that context, may be well suited for adoption across multiple communities with similar strengths.

COVID-19 Pandemic Context

Since the inception of the pandemic, the way we have approached shelters and access to services has been completely disrupted. Shelter’s safe occupancy rates have been cut drastically and what was once a refuge becomes a liability for infection. Service providers who were heavily staffed with volunteers found them losing their ability to meet needs without their workforce. Unprecedented numbers of people losing their employment and thereby their homes, has displaced a record number of people in our communities. With limited shelter options and little available housing, compromises have been made on how long and where the unsheltered can set up temporary residences. Undoubtedly, the pandemic has shown the fragility of our systems and has put a record number of people in our community in a vulnerable state.

Continuum of Care Context

The homelessness ecosystem currently is very fractured and lacks a consistent vision and strategies that will yield a holistic solution. This fracturing exists at the city and county level and each one of these regions has their own levels of tolerance or acceptability for the approaches. Some cities instituted camping bans, while others have left them unenforced, or considered repealing them. Some require residency for access to services. Some communities have even avoided admitting a need to address the issues of their residents who are experiencing homelessness. The case study examples have demonstrated the need for a cohesive and concerted effort with government, service providers and the public all aligned on the goals. Continuums of Care (a federal designation used nationally) help to garner funding and spread it out over a variety of needed service providers and spread over multiple localities. Currently some progress is being made in coordinating HMIS (Homeless Management Information System) data across the multiple continuums and across the communities they service, but this is a recent effort and will need wide-spread adoption to reach its full potential.

Systems Map

The overall systems map includes over 100 factors, and can be divided into eight thematic topics. The full map is shown in Figure 3. Each topic area is centered around an outcome that is either existing, and positive, or viewed as likely to be positive. Most outcome factors have precursor factors that are positively reinforcing and negatively reinforcing. Each topic area is intended to illustrate both angles and illustrate opportunities for supporting positive outcomes and reducing factors that diminish positive outcomes.

Feedback cycles in the systems map are a series of factors that each positively support the following factor, visually forming a loop. Connections between factors may be conditional, indicated with a label on the arrow. Other cases may have a time delay, indicated by two lines across an arrow, meaning that more of a factor over time builds up to a resulting effect, or there is a delay before an effect is realized.

The thematic topics that emerge from the systems map are:

- Housing Accessibility as an equity driver for homelessness

- Housing Affordability as an economic driver for homelessness

- Vulnerability as a state considered a precursor for homelessness, that can arise from many situations

- Trust in services and the system overall as a key to utilization of services

- Collaboration and Partnerships among providers to be able to best deliver services

- Technology Access and expectations as a barrier to accessing services

- Staffing as a key resource that enables high-quality services

- Outcomes that are desired goals and outcomes for those experiencing homelessness

Each topic area is explored in the following pages with a localized portion of the systems map. A description of the systems map is supported by vignettes and stories from community members, service providers, and organization representatives.

Figure 3: Overall systems map of Homelessness Ecosystem. Solid lines indicate that more of one factor leads to more of the connected factor. A dashed line is the opposite effect, where more of one factor leads to less of the connected factor. This map can also be seen online at https://kumu.io/axc/homelessness-ecosystem.

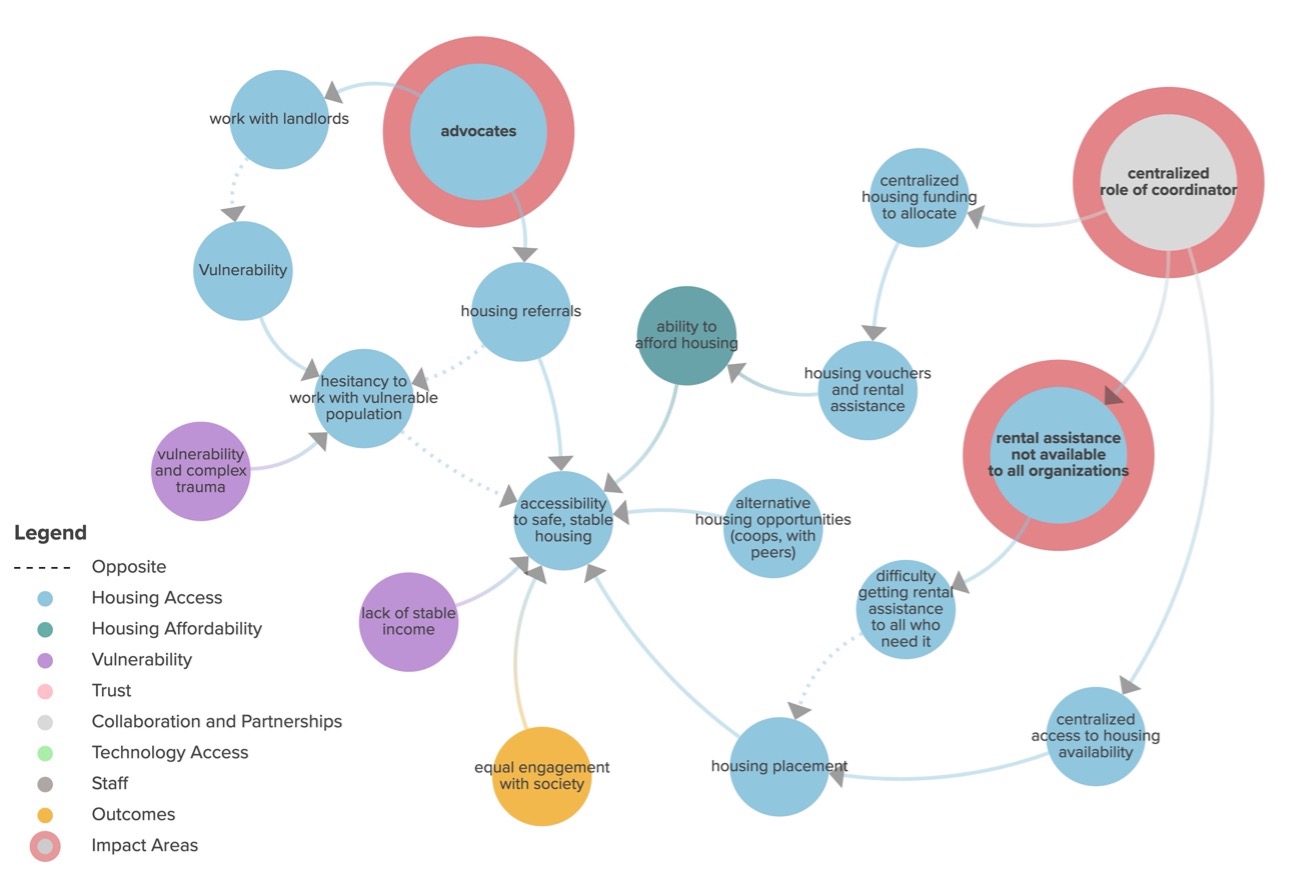

Housing Accessibility

Housing accessibility refers to the ability to secure safe and stable housing, including considerations beyond financial affordability. The factors that are related to housing accessibility are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Systems map segment centered around accessibility to safe, stable housing.

A focused coordinator within a network of service and housing providers is valuable to centralize the availability of housing options as well as financial support such as housing vouchers or rental assistance for housing. This streamlines the process for housing placement for individuals and families. However, a caveat that may arise from an incompletely integrated provider network is that rental assistance is not available or visible to all organizations to distribute. Increased ability for organizations to offer rental assistance can reduce the difficulty of getting rental assistance to all who need it rapidly. This may alleviate delays that can occur in the process to secure a housing voucher or credit, as well as access to a location where that payment can be used.

Housing advocates can play another critical role in the path to housing accessibility. Many individuals experiencing or having previously experienced homelessness are considered vulnerable, and the perception of vulnerability is considered a risk factor by many landlords or rental agencies. The VI-SPDAT (Vulnerability Index – Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool) is in use in Colorado and is a measurement tool to identify appropriate housing options for people based on their circumstances and needs. While the information collected from a VI-SPDAT assessment cannot be used explicitly to deny housing, just the perception of vulnerability can make landlords hesitant to work with individuals seeking housing. Further, the VI-SPDAT may not be consistently reliable in its assessment or as a predictor of housing outcomes. Housing advocates can help bridge this gap by facilitating interactions with landlords or providing housing referrals, provided that the advocates are perceived as genuine by those seeking housing.

Vignettes

VI-SPDAT is a widely used tool to assess risk in a housing option, but it is seen as invasive and not culturally inclusive. An extra barrier is the repeated interactions that can be required to fill out paperwork when specific documentation like birth certificates or social security cards are needed. Additional challenges exist for those leaving a homeless state in securing housing. Many landlords and housing management companies have questions and requirements around previous residences, previous evictions, job and income requirements, and former justice involvement. Finding available housing in a market that is already in short supply is difficult, and with perceived or real risks associated with your application it can be overly prohibitive to finding housing.

Summary

Opportunities to address the accessibility of housing options include expanding the number of organizations able to provide financial assistance for housing options, as well as supporting the work of trusted advocates to provide housing referrals and work with landlords to reduce negative assumptions about individuals considered vulnerable. Both opportunity areas are pathways to enhance the delivery of individualized solutions for people experiencing homelessness. There is a strong need to support pathways to housing for people in vulnerable situations, and support for those individuals in general, as described in Section 5c, also supports the opportunities for increasing housing accessibility.

Housing Affordability

One of the most direct factors influencing homelessness is the availability of housing at an appropriate price point for consumers. A lack of housing in Denver, as mentioned in Section 4 of this report, is attributed to strong market demand across all income brackets, and a rate of new housing built that is lower than population growth in the Metro Denver area.

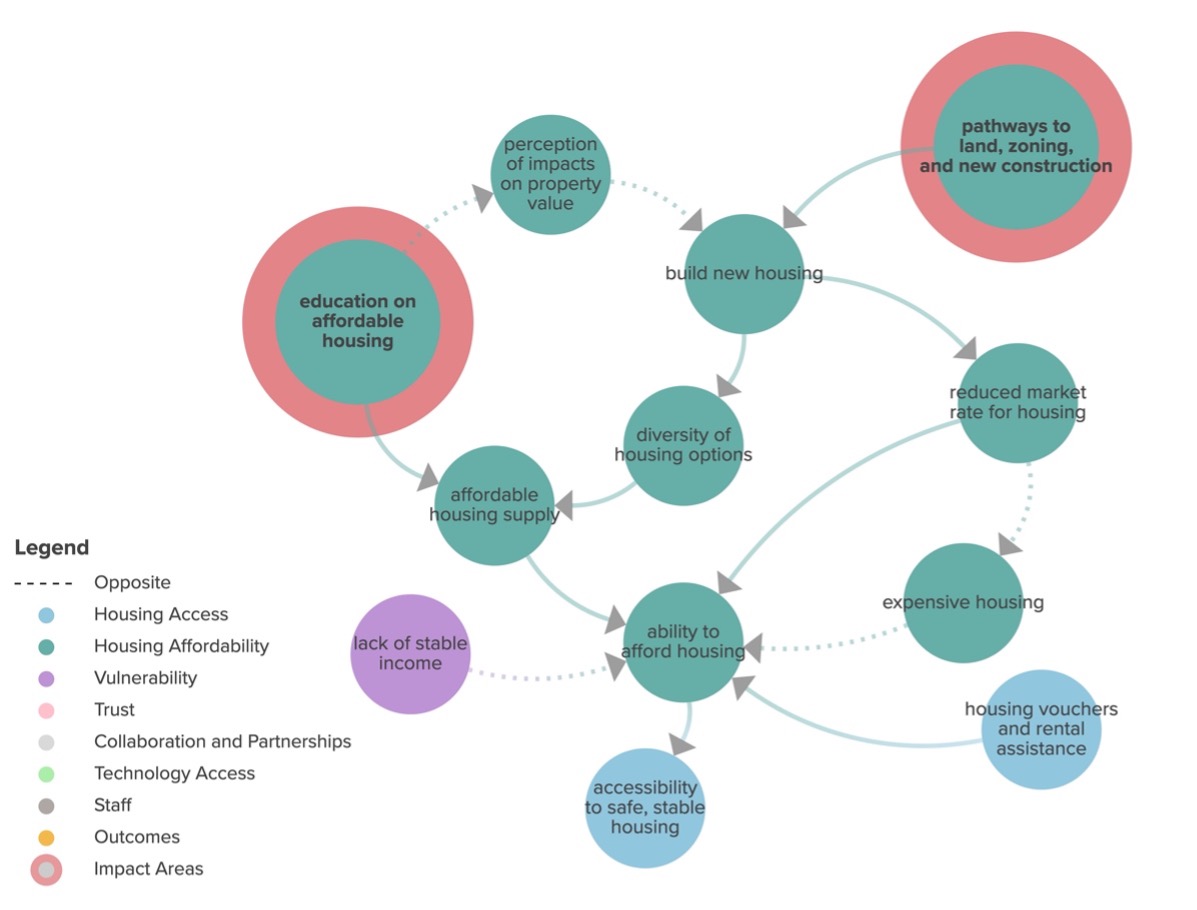

Figure 5 shows factors related to the ability to afford housing, including all types of housing (single family homes, apartments, multi-family housing, and affordable housing) options.

Figure 5: Systems map segment centered on the ability to afford housing.

Perceptions of affordable housing are a key negative impact on the development of affordable housing options, compounded by negative perceptions of growth overall that impact all kinds of housing development. Building new housing options of any kind is expected to both increase the diversity of housing options, as well as reduce the market rate for housing provided the supply of housing moves closer to the demand for housing. Alternative housing options such as peer matching programs or cooperative housing models are a different pathway to increase affordability of housing by using existing housing stock in different ways.

People can end up in a situation where housing is unaffordable for many reasons. Job loss or infrequent work opportunities leading to a lack of stable income, is one factor that can create or exacerbate an economic cliff. Job loss was often expressed as a factor leading to unaffordability of housing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other people must simply make a difficult choice between paying for housing or paying for other basic needs for themselves or their families.

Vignettes

Housing affordability is a problem that spans all of the Metro Denver community and those in danger of becoming houseless and those who are currently experiencing homelessness are affected more adversely. One nationwide affordable housing real estate developer shared that because of the zoning challenges and community pushback they have not been able to move any new projects in Colorado forward in 7 years. Denver’s Department of Housing Stability (HOST) shared that to develop a new single unit for affordable housing it costs upwards of $300,000 in the Metro Denver Area. With rising rental costs and a shortage of supply, many vouchers are unable to meet the gap between current prices and what people can afford. Some groups who assist with housing placement describe situations where a voucher will expire before it is able to be used because of lack of affordable options or companies willing to take them. Many developers have difficulty realizing multi-unit housing and communities adopt a “Not in my backyard” (NIMBY) stance, effectively blocking population density. Greater population density would potentially allow people to live in the communities where they work and prevent the need for increasing transportation and spending more of their income to maintain employment. One example of the results of this affordability issue is from Adams County, where the majority of those experiencing homelessness in their community are employed and living in their vehicles, in parks, and parking lots.

Summary

Additional pathways to building new housing or zoning allowances may allow additional new housing to be built in the Metro Denver area’s growing market. Opportunities also include education around the purpose of affordable housing and the types of people who benefit from affordable housing options, to reduce misconceptions that may exist.

Vulnerability

Vulnerability is a state of being susceptible to physical or emotional harm. Many situations can lead to an individual becoming more vulnerable, several common factors are shown in Figure 6: high usage of emergency services, health and mental health issues or crises, family instability, substance abuse, repeat experience in jail, and domestic violence are just some of the situations that can lead to or worsen vulnerability. Globally, these individual and social factors along with environmental factors like pollution or pests are recognized as factors that contribute to vulnerability and can result in a loss of housing . Critically, there are many pathways to become more vulnerable, and those pathways compound to produce complex trauma. Individuals with complex trauma or high levels of vulnerability are more likely to end up in a dangerous situation, meaning a higher need for immediate shelter.

Figure 6: Systems map segment centered around vulnerable population and people with complex trauma.

Higher vulnerability means lower accessibility of stable, safe housing – a profound block in the pathway to housing and ending homelessness. Individuals in a highly vulnerable state or with complex trauma may not fully understand their situation, or may feel they are forced to choose which barriers they face to address with the money they have.

There are few current pathways out of a vulnerable state, which rely on persistent engagement by service providers and consistency of care provided, as well as enhancing the availability and accessibility of information so that individuals who may be experiencing homelessness or grappling with a situation where they may lose stable housing can build confidence in resources available, and build courage to comprehend a change or transition from their current situation.

Vignettes

There are an exponential number of ways for a person to find themselves in a vulnerable state and at risk of being houseless. Not only are there many factors that may lead to homelessness, but multiple factors can also compound to reinforce an increasingly vulnerable position. One reference that was offered is “that the only consistent predictor of those who may become homeless, is that they have been homeless previously.” Social determinants of health may leave families in generational poverty and leave them more susceptible to being in a vulnerable state. Low income, or lack of financial education may leave individuals with little to no safety net for retirement. Domestic violence or abuse may leave partners and children with difficult choices between abuse with financial stability or homelessness.

Summary

Key opportunities in this area are to reinforce the consistent and persistent support for individuals in vulnerable situations so that they can be reached, supported, and helped before that help is critical.

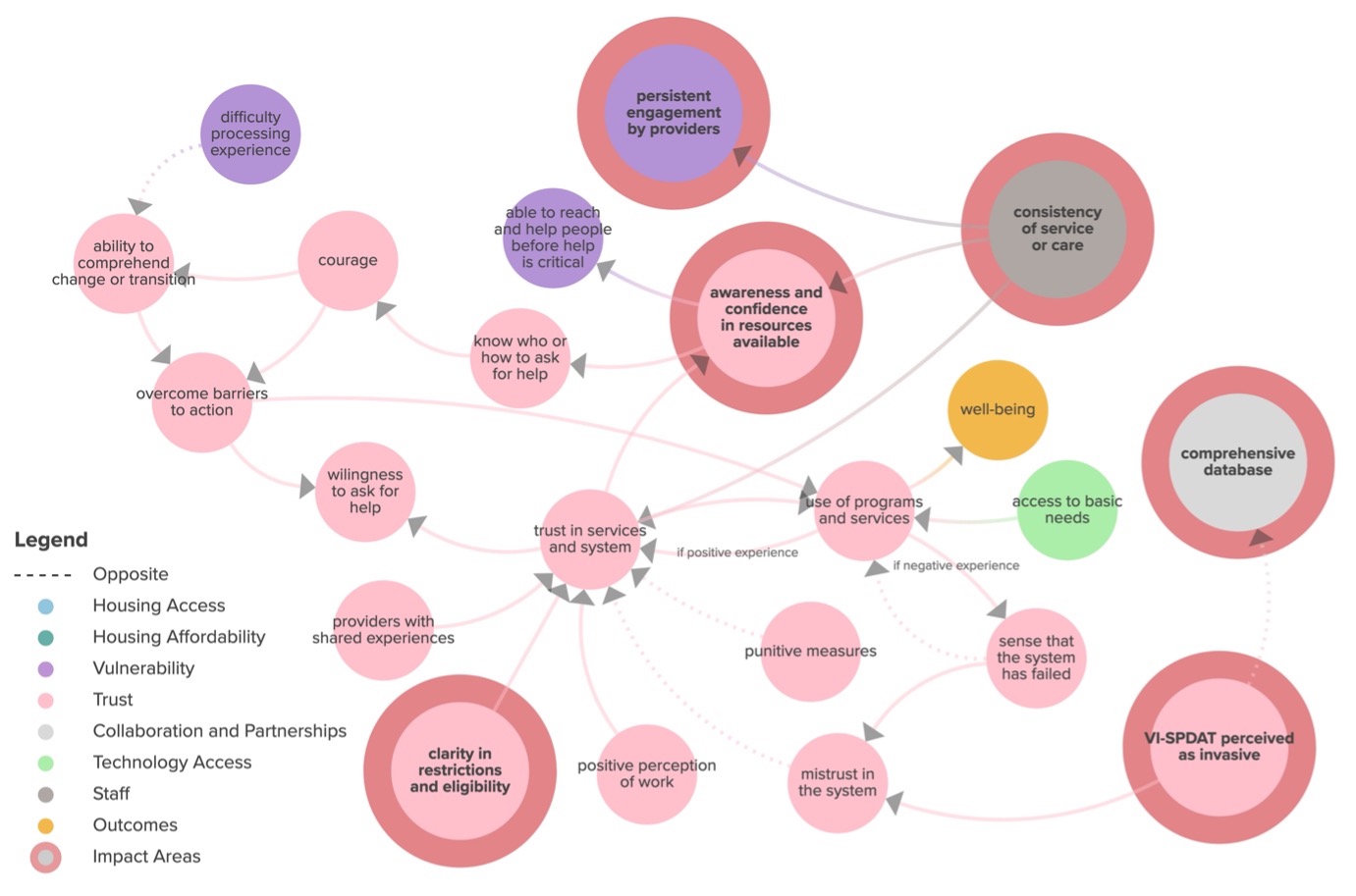

Trust in Services and the System

Trust in providers is a key driver of use of programs, services, and housing. Trust comes from varied sources, including a positive perception of the provider’s work in the community, reliable service or care, providers having shared experiences such as having previously experienced homelessness, and clarity in restrictions or eligibility requirements for care. Punitive measures such as warrant checks decreases trust in services or providers. The factors that impact trust and the multiple pathways that trust enhances use of programs and services are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Systems map segment centered on trust in providers and services, and the use of programs and services.

Increased trust in providers yields increased awareness and confidence in resources available, meaning people know who or how to ask for help when they need it. The knowledge of how, and who to ask, for any kind of help builds courage, which can help to overcome barriers to action that may exist. These barriers take the form of unwillingness to ask for help, frustration with the system – referring to care, legal or justice, housing, or even broadly reflecting frustration with society. The courage and willingness to ask for help is a primary mode for use of services.

First impressions from providers of all kinds of services or housing programs are critically important as even a single negative experience can create a feeling that the system has failed an individual. More of this negative impression decreases the usage of programs and services, such as housing programs or shelters. Additional avenues to explore are the indirect costs (fiscal, environmental, and social) that is incurred by these negative impressions and avoidance of services.

A factor that has strong leverage in this cycle of trust is the clarity in eligibility requirements. Eligibility varies by provider, and different restrictions apply to people in different situations. Some eligibility restrictions or requirements are set by funding sources, some may be legally mandated, and others may be set by individual providers.

Clarifying and streamlining restrictions and eligibility requirements for people seeking information is a key opportunity. This extends to the general public as well, as transparency and streamlining requirements for services helps everyone to better understand how the system works and what gaps exist.

Vignettes

One individual who formerly experienced homelessness shared that within that community there is a distrust of the system and many are fearful of engaging with providers. The individual now runs a nonprofit organization and provides services without any restrictions or conditions. They also have vetted service providers join their events along with others who formerly experienced homelessness to provide support and show a pathway out of that situation. Many individuals experiencing homelessness have had experiences with programs or housing that were unsuccessful in previous attempts and overcoming the fear of trying again can also manifest as a distrust in the systems or approaches. A transition into unfamiliar housing can be daunting. However, repeated interactions and built trust can yield nearly 100% uptake of housing services, such as was seen through the Social Impact Bond program in Denver. Only a few accepted the offer of support housing on first contact and many individuals needed to be convinced of the program before accepting. Trust needed to be built over 3 or 4 repeated entreaties by SIB staff.

Summary

Key opportunities to enhance trust in providers, and to positively influence the usage of programs and services therefore are enhancing clarity in restrictions and eligibility requirements for services, as well as enhancing the awareness and confidence in resources available for those experiencing homelessness.

Collaboration and Partnerships

Collaboration and partnerships between organizations enable individually tailored services and increase organizations’ ability to guide people to appropriate services and ability to share resources efficiently. The segment of the systems map shown in Figure 8 shows some of the factors related to effective collaboration and partnerships between organizations. At a basic level, many organizations simply cannot exist without partners. Strong partnerships are only possible if organizations are aware of each other, and at a systems level strong leadership is needed to ensure coordinated vision and strategies for action. Enhancing marketing and outreach efforts is an apparent opportunity for increasing awareness of the organizational ecosystem, as marketing and outreach efforts often fall outside critical staff tasks of delivering services, as is developing and recognizing a centralized coordinator role in this space.

Figure 8: Systems map segment centered on collaborations and strong partnerships to support ecosystem.

Organizations working together in a collaborative nature allows individual organizations to specialize, which can build a reliance on other organizations to play their role in a partnership. This kind of specialization also allows for a focused role of a coordinator, which may be situated in a local government. These coordinators do not necessarily directly deliver services, but can play a role in centralizing information and resources, allocating those resources, and advocacy for the individuals served by the services coordinated. A possible blind spot is that a strong central coordinator necessarily also means that resources like centrally distributed rental assistance are not available to multiple organizations to distribute, possibly presenting as a bottleneck. An enabler of the ability to coordinate services is a view of aggregate data, aiding understanding of who is providing services, who is utilizing services, and where gaps may exist in coverage or service utilization. Data collection is fraught with disparate data collection tools and perceptions of the data collection process based on short, but impactful touchpoints with individuals experiencing homelessness.

Vignettes

In many ways coordination and collaboration is essential for the success of organizations. One organization provides temporary housing, but needs to send their clients to other organizations for mental health services and drug treatment programs. The Homelessness Leadership Council was highlighted as a good example and allowed many organizations to have visibility to what others were doing and provided a coordinated focus to the issues that arose throughout the pandemic. Collaboration with public institutions like schools can help identify youth who may be experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. Another area where coordination and collaboration is valuable is in the successful housing of all individuals, especially those chronically unhoused, by matching housing programs with supportive services that meet each individual’s needs. There are still opportunities to coordinate resources: needs vary from individual to individual, and a robust system to connect resources can enhance each organization’s ability to serve their current clients.

Coordinated systems that help give clear and concise information on individuals experiencing homelessness also help with providing services quickly and efficiently. A Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) is a consistent touchpoint in this area and efforts like Built for Zero provide a framework for the data that makes enhanced coordination across the city, county, and state possible. When used well they can help reduce individual staffing needs at each point in the continuum and also track progress and reduce interruptions in care.

Summary

Different organizations have a different view of their ecosystem of providers, data availability, resources, and priorities. Key opportunities in this space are to enhance organizations’ awareness and visibility of each other, perhaps via marketing or outreach efforts, support centralized coordination to ensure awareness across providers in the ecosystem, and centralized information availability to enhance organizations’ ability to understand the needs in the space they work and serve.

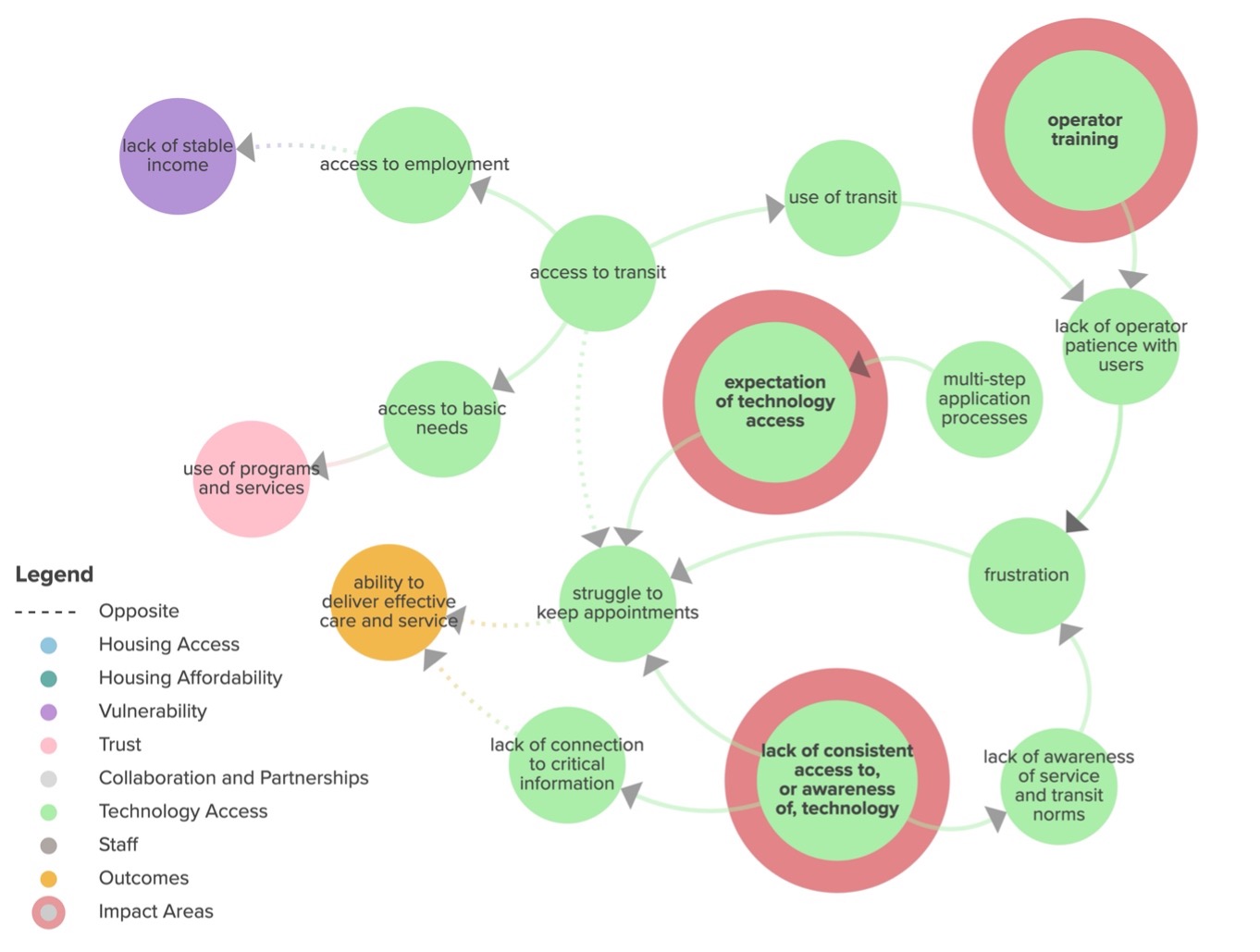

Technology Access and Expectations

For people who are experiencing homelessness, expectations of access to technology along with inconsistent access to technology impacts access to care and public services. This can include access to important paperwork required for housing applications, medical appointments, ability to pay bills on time, and transit services. Factors related to technology that can impact the ability to deliver care and service tailored to an individual’s lived experiences are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Systems map segment focused on technology considerations centered around the ability to deliver care and service tailored to lived experiences.

A lack of consistent access to technology for those experiencing homelessness can manifest as infrequent access to wireless internet, access to electricity for charging devices, or a lack of regular access to a device for communication or for internet access. This lack of technology access leads to a lack of connection to critical information, which may be related to health, work, housing, legal issues, caring for one’s finances, or any other need.

For providers, this inability to regularly or reliably engage with the community they serve directly impacts ability to deliver service or care in a way that makes sense for every individual. Tailored to an individual’s lived experience means that each person seeking service or care may receive different services, which may mean a sequence of appointments, a set of different providers, or a single appointment. A compounding factor is an expectation of technology access, built into multi-step processes for healthcare, services, application processing, or phone calls where a participant on either side is not readily reachable.

Access to transit is a key part of access to needed services and employment opportunities, which can be hampered by a lack of awareness of services and transit norms. A lack of operator patience with users results in frustration for all parties, and frustration with experiences can increase an inability to keep appointments, further setting back providers’ ability to deliver care, meet basic needs, or find stable employment. Operator training may be one opportunity to disrupt this negative cycle.

Vignettes

Technological challenges exist at many levels and for all parties. Through our interviews we have learned that individuals experiencing homelessness lack consistent access to technology that they control which makes transit, healthcare, legal issues, meeting deadlines, keeping appointments, and paying bills extremely difficult. Tracking and staying connected with clients is a similar challenge for providers and prevents consistent care. Many types of programs require regular check-ins and timely responses to applications to be successful.

Summary

Key opportunities in this space are around recontextualizing the expectation of technology access for all users of services, increasing the ways to consistently access technology resources or build awareness of services or norms around services, and training for public service operators to work positively with patrons who may not be aware of norms.

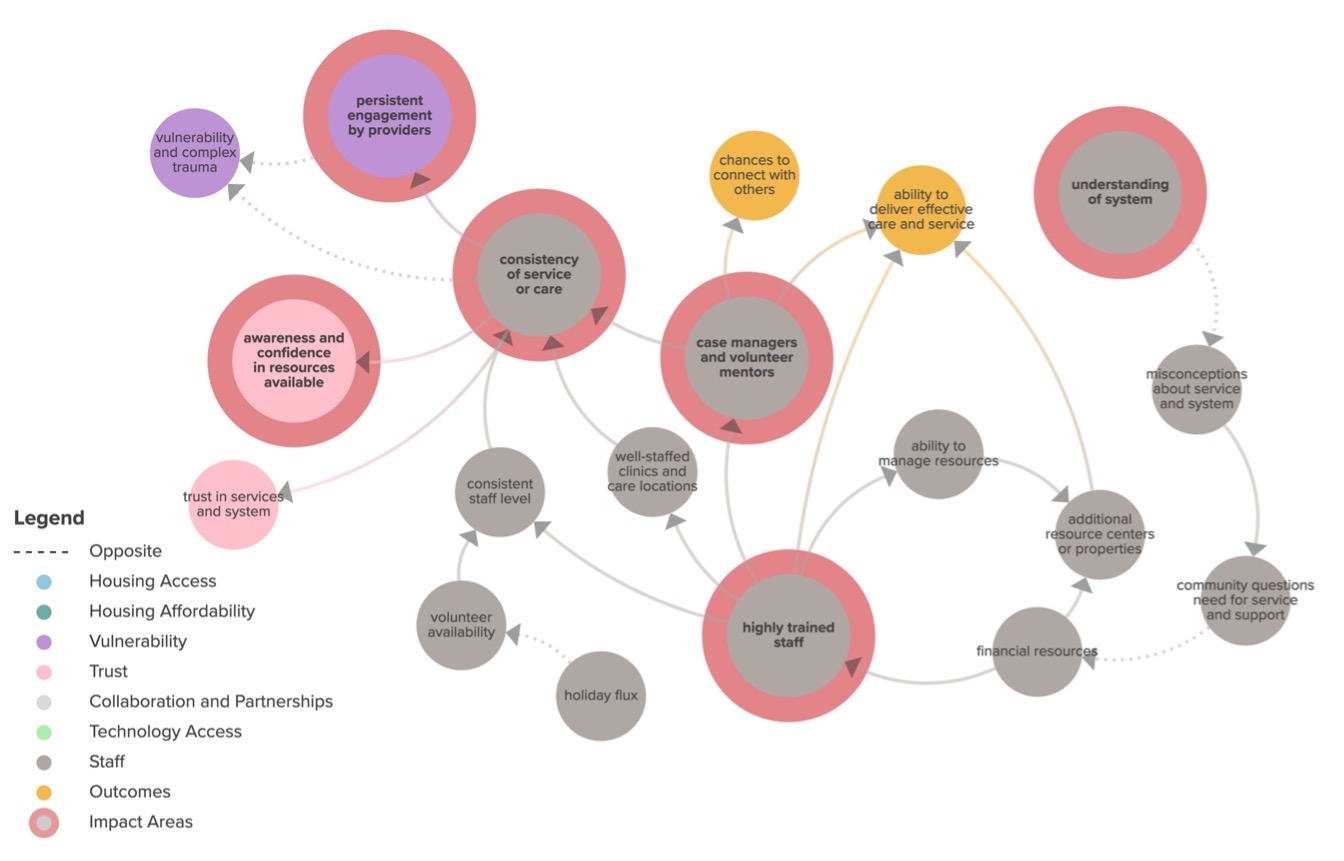

Staffing for High Quality and Consistent Care

Staff availability is a primary concern for many of the organizations contacted as part of this analysis. Two goals of providers are the ability to maintain a consistent staffing level and deliver reliable service or care. The availability of highly trained staff allows both of these goals, and additional outcomes, to be met. Factors related to staffing considerations are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Systems map segment centered around consistent staff level and reliable service or care.

Many organizations have a volunteer staff, and those volunteer networks can be very effective. However, not all volunteers have the training to deliver specialized care, manage physical, personnel, and monetary resources, or be able to put in extra time beyond core critical operations to fundraise or network with other organizations. These tasks usually require trained or specialized staff, which in turn are more expensive for an organization to retain.

Vignettes

When groups were asked what some of their biggest needs were, many of them pointed to the need for skilled staff who are able to show consistent professional support to their clients. Many also depend heavily on volunteer assistance and without consistency many areas of need fall on the staff (administrative and fundraising tasks are common examples) and can be put aside in favor of more pressing work. Efficient navigation of the system and successfully guiding clients through challenges comes with work experience and, when successful, builds trust in both programs and the system as a whole.

Summary

Pathways for organizations serving those experiencing homelessness in any form to retain skilled staff, as well as education around the work that those organizations do are key opportunities in this space to ensure consistent, high-quality, and reliable service or care.

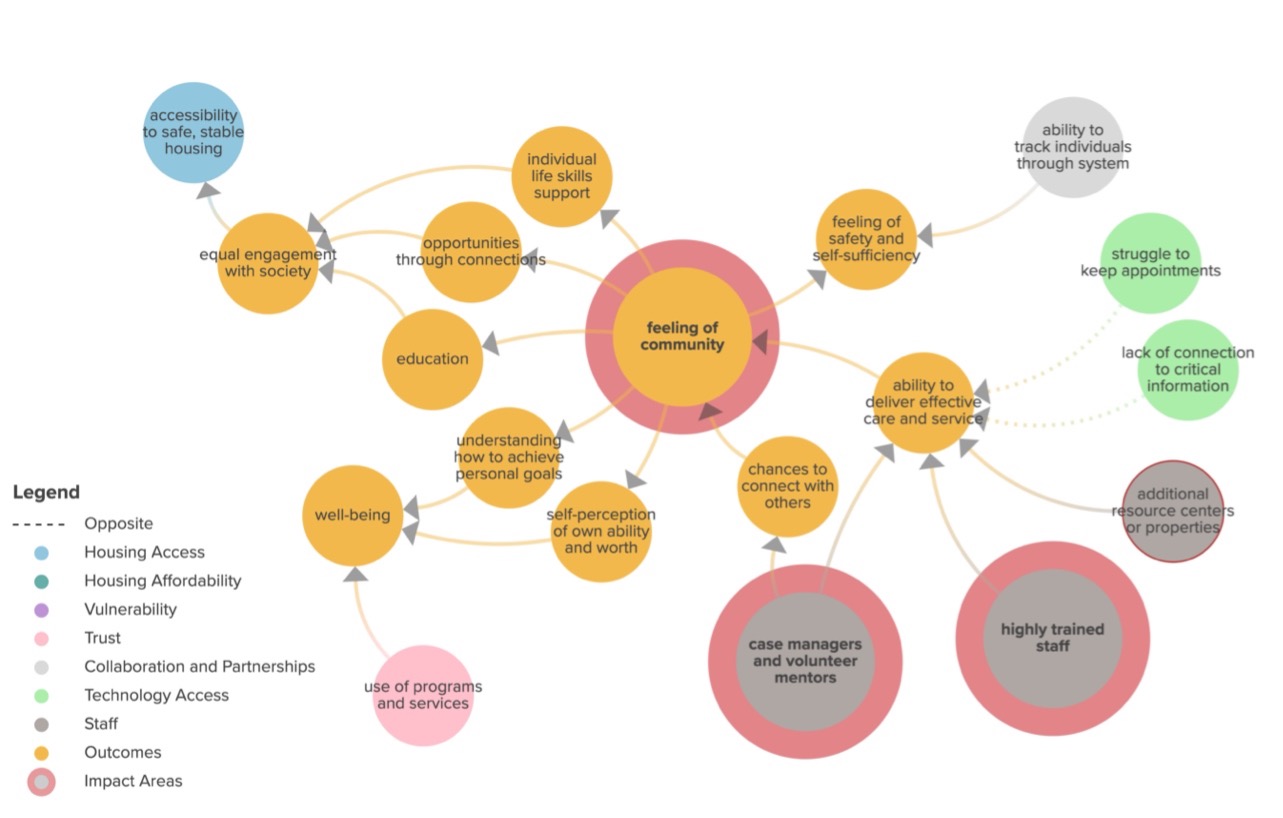

Community-Based Outcomes

Positive outcomes are different for every individual and contextual to their situation and needs. A key factor that is present in many visions of positive outcomes is building a sense of community. A feeling of community is developed and reinforced by many factors: chances to connect with others with shared experiences and service or care tailored to one’s lived experiences are enabled by case managers and volunteer mentors. Building life skills, education, and opportunities to connect with others reinforce the feeling of community. A deeper sense of community leads to higher well-being, feeling of safety and self-sufficiency, and equal engagement with society. Factors that enhance and lead from a feeling of community are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Systems map segment centered around positive outcomes identified for individuals experiencing homelessness.

Dedicated case managers and volunteer mentors can make a large difference for individuals through their work to deliver services and facilitate meaningful connections and networking. A case manager’s work is also facilitated by the availability of information to longitudinally track individuals through the care or services they may have received. This especially correlates with the ability to deliver tailored service or care.

The outcomes from a feeling of community are large social gains: an improved self-perception of own ability or worth, and a better understanding of how to achieve personal goals are example outcomes that are related to a higher sense of well-being. A community as well provides a sense of safety, and self-sufficiency in the context of the community. Finally equal engagement with society, from development of life skills, education, or new opportunities through connections, is a pathway to accessible, stable, and safe housing.

Vignettes

One service provider framed the issue of homelessness as “a loss of community.” When homelessness is a result of loss of community, then finding ways to welcome individuals into a new community is necessary. Support and guidance leads to trust and brings increased courage to take on greater responsibilities. A sense of accomplishment brings feelings of self-worth and well-being. However, this path is not always straightforward. Stigmas and systemic boundaries can prevent individuals from rejoining society after incarceration, eviction, prolonged periods of joblessness, or returning from experiencing homelessness. Individual cases require personal approaches and that may need to include multiple types of services for complete rehabilitation.

Summary

Opportunities to enhance positive outcomes are supporting the growth of community and the positive mechanisms it can build. A genuine and trusting community can in part be supported by the work of case managers and volunteer mentors to deeply engage with individuals in ways that are tailored to each individual. In turn, there are opportunities to enhance the availability of care data in a way that is respectful to the originators and beneficiaries of that data.

Highlighted Impactful, Innovative, or Unique Practices in the Denver Metro Area

While learning about the homelessness ecosystem, we came across many talented, dedicated people taking on challenges in their community. We have highlighted a few of the programs and initiatives below that are unique and bringing new approaches to this system. Many of these initiatives are in pilot or testing mode and will have further development ahead to see their full potential. Some are also very specific to their area of the systems and provide only temporary solutions. For each impactful, innovative, or unique practice below, pros and cons are identified.

Prioritization for allocation of services

Value and Impact

Metro Denver Homelessness Initiative has engaged C4 Innovations , an organization advancing equitable housing solutions across the country to create a dynamic approach to prioritization. The process has started in mid 2021 and we look forward to its speedy progress. This could provide a much-needed update to the allocation of resources and address the lack of equity and flexibility in the current methods. Their goal is not to replace the VI SPDAT, but to create a better and more inclusive way to prioritize those entering the system.

The current process, which has been in use in many places for over a decade, makes use of a short questionnaire (VI-SPDAT) that gauges morbidity and makes a risk assessment based on the respondent’s answers. While short, a risk assessment used for prioritization in services is a critically important touchpoint and an opportunity to meet individuals where they are to identify services best suited to their situation. VI-SPDAT has been seen as not responsive to the broad community of people experiencing homelessness, or seen as a difficult tool to implement as it requires individuals to divulge deeply personal information about possible sexual assault or exploitation, physical abuse, trauma, and events that may cause them great embarrassment to a stranger in an initial short interview (as little as 7 minutes). This can be a difficult process for many people and may run counter to certain groups communication norms. As responses are voluntary and not based on public record, an omitted response out of sensitivity or forgetfulness may result in a lower prioritization for services.

Connection to the map

VI-SPDAT perceived as invasive, clarity in restrictions and eligibility, trust in services and system, awareness and confidence in resources available, accessibility to safe and stable housing

Pros and Cons

Pros: If a more equitable and flexible prioritization method is created and adopted widely by the community then it would make large strides towards rebuilding trust in the overall system and reaching marginalized groups more effectively.

Cons: Any prioritization or entry mechanism holds an outsized amount of power over an individual’s access to services. With finite resources available and a spectrum of individuals and families experiencing homelessness, some ways must be employed to help those most in need.

Built for Zero

Value and Impact

Built for Zero is an initiative that has been implemented in 89 different communities across the country and has begun crossing borders to other countries. It works toward a state called “functional zero”. In essence, Functional Zero is when the number of new people, usually from a defined group of people such as military veterans or ex-wards of the state, using homelessness services (such as shelters etc.) in any specified time period (e.g. each month) and in a specified region (e.g. a town, city or state) is less than or equal to the number of people who exit homelessness through being housed or leaving the region (or dying). Functional zero is achieved through a coordinated approach that focuses efforts toward a specific population within the sub-groups experiencing homelessness. Most communities tackle veteran homelessness or chronic homelessness as the first sub-group. Focusing on veteran homelessness allows communities to build off of government support already provided and build expertise and partnerships that can be leveraged for further successes.

While many efforts are limited by city, county, or state lines, this effort is different from the norm by seeking to build better unified teams to tackle homelessness from a broader context. The approach is one of better utilization of resources through real-time person-centric data collection and hosting and sharing with providers. This likens them more to an emergency response to a health crisis or natural disaster. They build a command center of decision makers and homelessness community leaders and are able to be nimble in addressing emergent needs and keep an urgency to the work. It also has a strong focus on collaboration with other stakeholders in the community, mentorship, and cohorts or other providers facing similar challenges in other communities.

The Built for Zero approach begins by doing an assessment of the community that is seeking to implement the program. This allows an understanding of the community and its systems. Often, they are engaged by a healthcare institution or leaders within a Continuum of Care that serves as an anchor institution. Next, they build out their command center. This group holds regular meetings and knows how to influence the local community and where key data is located or how to access it.

The command center of community decision makers, continuum of care, and providers builds a by-name list and begins analyzing from several areas of interest. How effective is the communication? What is the level of local buy-in? How easy is it to access and track? What systems may need to be built? How is coordinated entry being managed? A quality by-name list (QBNL) will provide consistent and timely data that can be used to accurately identify trends, needs, and progress towards ending homelessness. To be considered quality, your by-name list must be able to account for every individual experiencing homelessness. The list must have a reliability margin of 15% over a 3-month period. Inflows and outflows are accounted for and those moving through the system are tracked.

After the assessment is done and the command center is convened, they begin an improvement plan that outlines what changes are required to get each area working at the level needed. Concurrently, teams are connecting with others and building capabilities and learning new or augmented approaches. Cohorts are created to help others in each space and to develop and share best practices. There is also a gathering of groups over a 4 day period to look at trends, successes, and challenges that affect those working to end homelessness. Colorado has its own cohort that is focused on issues of import within the state.

As successes happen, teams gain confidence in the system and are able to work more cohesively with their other collaborators and access data that makes their work more effective. Communities that have achieved functional zero in a sub-group population are able to shift focus and bandwidth to prevention and maintaining a functional zero state.

The Colorado cohort, now composed of nine teams, supports an estimated 90% of people experiencing homelessness in the state. The action-focused, state-level team includes representation from public, private, healthcare, indigenous, veteran, and CoC agencies, with primary leadership stemming from the Office of Homeless Initiatives (OHI) within the Division of Housing, Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA). Two other agencies play key roles — the Colorado Department of Human Services and the Department of Healthcare, Policy, and Financing — with Kaiser Permanente Colorado and the Colorado Health Foundation rounding out the partnership. This would cover the 4 Continuums of Care (all in Colorado) with a footprint of 21 counties. The first population groups they have focused on are veterans, with some including chronic homeless, early successes have already been shared. Fremont County has reached functional zero for veterans and that effort helped expose systemic challenges that needed to be addressed for the broader community of veterans experiencing homelessness.

Connection to map

Comprehensive database, collaborations and strong partnerships, coordination of services, continuum of care focus, ability to deliver effective care and service, staffing

Pros and Cons

Pros: Better coordination prevents wasted efforts, gaps in coverage for the communities and provides much needed focus on strategic evidence-based approaches to specific groups experiencing homelessness. The Community Solutions group specifically highlighted that homelessness is solvable and the approach has achieved success in many communities. One specific benefit that bears notice is that when this system is fully engaged and they have reached a “quality” status with their data, they can be very specific with their needs, the implementation, and efficacy of certain actions.

Cons: Some groups have highlighted that much effort is spent on the entry points and data collection, but lack the same level of effort to the largest and most difficult issue of housing shortages and housing accessibility.

Clustering and Decriminalization approaches

Value and Impact

It is estimated that 40-60 percent of people held in county jails in Colorado are there for failing to appear in court. Boulder has implemented a new approach to municipal warrants called warrant clustering. The basic premise of warrant clustering is that for non-violent crimes committed by individuals experiencing homelessness, the county waits to issue warrants until the individual has reached a threshold of three cases that they have failed to appear on. Once that threshold is reached, then Boulder “clusters” the warrants together so that one arrest is used to address those three cases. If someone does not meet that threshold, meaning they get one or two non-violent cases where they fail to appear, then after six months, their cases are dismissed.

Prior to warrant clustering, if someone failed to appear on a littering ticket (as an example) then they would have an arrest warrant active for four years. Warrant clustering added an extra step to the warrant process by ensuring warrants only went out for violent cases and for people who are committing multiple quality of life type crimes and not engaging in the legal process voluntarily.

Connection to map

Trust in services and system, clarity in restrictions and eligibility, use of programs and services, equal engagement with society

Pros and Cons