AUTHORS: SIMON LOMAX AND CHRIS BROWN

MAY 2020

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Simon Lomax is the Common Sense Policy Roundtable’s Energy Resources Fellow. He is a former congressional fellow with the American Political Science Association and a former energy and environmental reporter for Bloomberg News. Since 2012, he has worked with think tanks, trade associations and business groups to advocate for limited government and free-enterprise approaches to public policy. Before joining CSPR, he previously served as a research fellow for Vital for Colorado and as an associate energy policy analyst for the Independence Institute.

Chris Brown is the Director of Policy and Research with the Common Sense Policy Roundtable where he leads the research efforts of CSPR to provide insightful, accurate and actionable information on the implications of public policy issues throughout the state of Colorado.

ABOUT COMMON SENSE POLICY ROUNDTABLE

Common Sense Policy Roundtable is a non-profit free-enterprise think tank dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy, our mission is to research and promote common sense solutions for the most pressing public policy issues facing Colorado. We examine the economic impact of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws by employing dynamic modeling that accurately measures the impact of each measure on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity. To fully achieve our mission, we actively promote these solutions through the education of policy experts, lawmakers, community leaders, and the general public.

CSPR was founded in 2010 by a concerned group of business and civic leaders that saw divisive partisanship was overwhelming the issues, and objective economic analysis was not being presented to lawmakers and voters empowering them to make fact-based and common sense decisions.

Executive summary

Following similar efforts in 2014, 2016 and 2018, a series of ballot measures targeting the state’s oil and natural gas sector have been proposed for the November 2020 election.i These ballot measures are primarily focused on restricting the availability of land for energy development through the use of setbacks. Setbacks are minimum distances between proposed new drilling sites and specified locations. In the case of the proposed 2020 ballot measures, the setbacks apply to list of structures and geographical features found in urban, suburban, rural and uninhabited parts of the state.

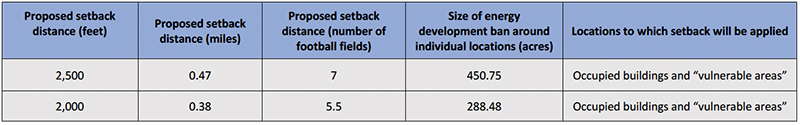

Setbacks create a circular area around an individual location where energy development is banned. Across several 2020 ballot measures, two different setback distances have been proposed:

When they are applied broadly, setbacks can have a sweeping impact, preventing energy development across wide areas. For example, in 2016, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources determined a 2,500-foot setback – applied to occupied structures and a list of other locations identified by environmental activists – would result in a drilling ban covering approximately 90 percent of the state’s land mass.ii This is because the 450-acre drilling ban created around one location would be multiplied millions of times across all the other locations that trigger the setback.

The setback distances proposed in the 2020 ballot measures are not new. In 2018, a coalition of environmental groups placed a setback of 2,500 feet on the ballot, which voters ultimately rejected. In 2014, environmental groups supported a ballot measure with a setback of 2,000 feet, but the initiative was withdrawn before completing the signature verification process.

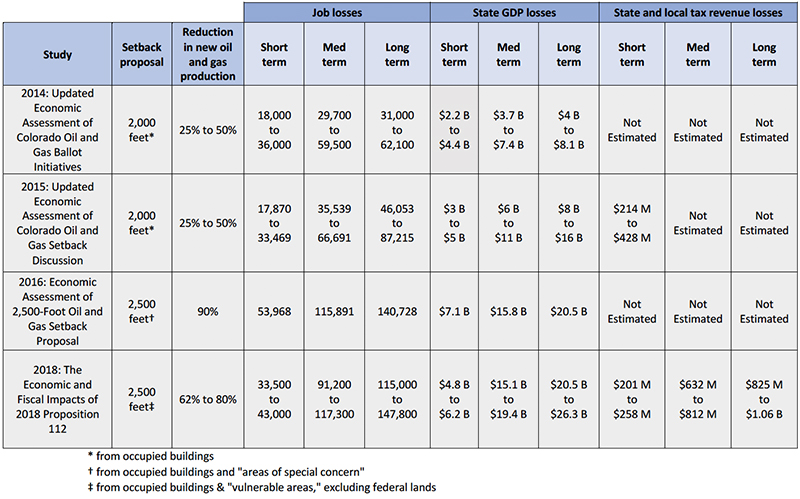

In response to these proposals, the Common Sense Policy Roundtable, supported by staff at the Colorado School of Mines and the Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado, has conducted research and produced a series of studies over the past six years to quantify the potential impact of various setback measures on jobs, economic activity and tax revenue, among other economic indicators.

This report examines the findings of these studies and any lessons that can be applied to future analysis in response to the 2020 ballot measures. Specifically, we reviewed the short, medium and long-term projections in these studies over a time horizon of 12 to 15 years.

Setback studies from 2014-2018: Key findings

The findings of these studies provide an important foundation for future research, particularly an examination of the impacts of the 2020 setback ballot measures. Our review also identified some areas where methods and assumptions may need to be updated, including:

- Geographical information: Studies in 2016 and 2018 relied on geographical reports produced by the State of Colorado. These reports significantly improved the understanding of setbacks, but there were limitations in the data. For example, location data was unavailable for several categories of vulnerable area and location data for occupied structures in more than one-quarter of Colorado counties was either non-existent or out of date. Therefore, these limitations may have underestimated the total land area impacted by past setback ballot measures.

- Expansion of 2,000-foot setback beyond occupied structures: Prior research into 2,000-foot setbacks applied this distance to occupied structures. However, the 2,000-foot setbacks proposed this year would apply this distance to both occupied structures and vulnerable areas. This change will significantly expand the impacts of a 2,000-foot setback. Until the impact of this expansion is quantified, it should be noted that prior research into 2,000-foot setbacks does not account for vulnerable areas and likely underestimates the impact of more recent proposals by a wide margin.

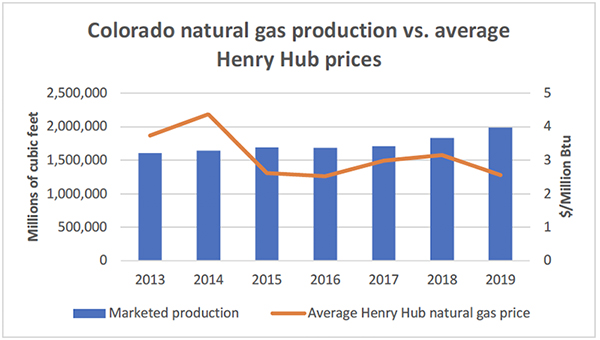

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

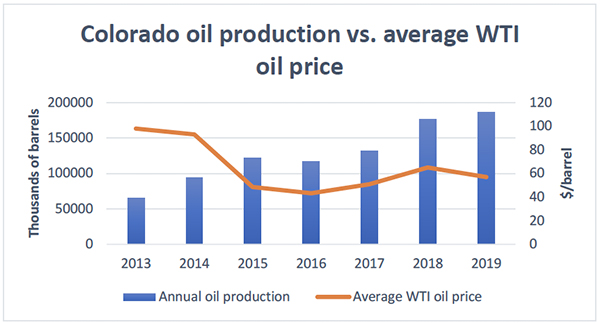

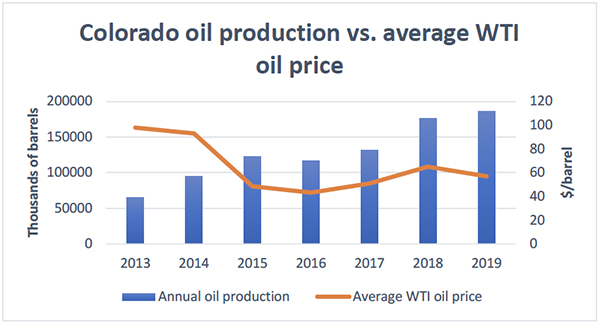

- Growing production and changing economics in the oil and natural gas sector: Colorado’s oil and natural gas sector has changed significantly since research into setback ballot measures first began. State oil production, for example, increased 183 percent between 2013 and 2019 – even as average oil prices fell by 41 percent over the same period. Accounting for these efficiency improvements may improve understanding of the impacts of setback ballot measures, especially in light of recent drops in energy prices.

While awaiting updated research, examining past studies into setbacks can provide policymakers and the public with a directional sense of the impacts of new ballot measures that are currently proposed for the 2020 election. A review of past studies can also identify help fine-tune the methods and assumptions that will underpin future research efforts.

In summary, the current body of research indicates Colorado would experience major losses across the private and public sectors under setback proposals of between 2,000 feet and 2,500 feet. These impacts would start with job losses in the tens of thousands, economic losses in the billions of dollars, and lost tax revenues in the hundreds of millions of dollars, with significant escalation of these impacts over time.

In the context of today’s massive global economic slowdown, these impacts may take on a new significance. CSPR is closely tracking the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the state economy, iii and in just the first two months of the COVID-19 lockdown, more than 400,000 Coloradans filed for unemployment – a number that exceeds 16 percent of the state’s total workforce. The impact of shuttering businesses or limiting operations to slow the spread of COVID-19 has also greatly reduced tax revenues. At the state level, budget writers are facing an immediate shortfall of roughly $3 billion for the upcoming fiscal year, and reduced revenues could persist for years depending on how quickly people can get back to work and businesses can return to growth.

Surging unemployment levels and plummeting tax revenues are just two of the daunting challenges that Colorado will have to overcome in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. A major drop in oil prices – triggered by the fallout of COVID-19 and a price war between some oil producing nations – has also impacted Colorado’s energy sector and the broader state economy. Taken together, these recent developments put this year’s setback ballot measures in a new light: If public policy prevents one of Colorado’s largest industries from ever recovering, how much longer will it take the state as a whole to recover from its present economic troubles?

Even in good times, setback ballot measures have the potential to cause serious economic consequences for working families, businesses, school districts and other public services funded with tax revenues from oil and gas production. How, then, will these consequences be felt in challenging times? That is the key question that future research must address in order to promote a full, fair and timely debate over setback ballot measures in the weeks and months to come.

Setback studies in Colorado: An overview

In recent years, environmental groups have proposed a series of ballot measures that would increase setbacks on oil and natural gas development. A wide range of setback distances have been proposed, but two setback distances have received the most attention: 2,500 feet and 2,000 feet.

In 2018, a 2,500-foot setback measure – Proposition 112 – was put before Colorado voters and failed to pass. In 2016, a similar measure was proposed but did not amass enough signatures to qualify for the ballot. In 2014, signatures for a 2,000-foot setback ballot measure were gathered and submitted, but the ballot measure was withdrawn before the signature verification process was complete.

With the emergence of setback ballot measures came heightened interest in their economic impacts, especially because many of the same groups supporting setback ballot measures had also expressed support for banning oil and natural gas development statewide. To help voters and policymakers, the Common Sense Policy Roundtable has conducted research on a series of studies exploring the questions raised by setback ballot measures.iv

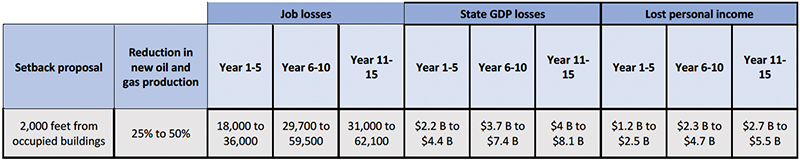

2014: Updated Economic Assessment of Colorado Oil and Gas Ballot Initiativesv

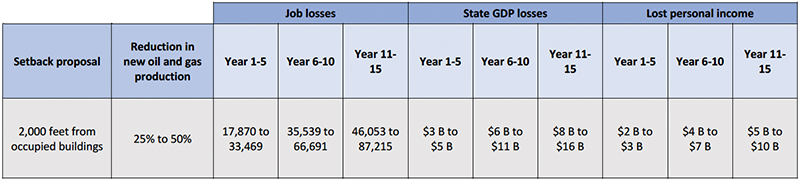

Using the CSPR’s dynamic economic model – licensed from Regional Economic Models Inc. (REMI) – the University of Colorado’s Leeds School of Business produced an analysis on Initiative 88, which would have applied a 2,000-foot setback from occupied buildings.

The authors of the analysis estimated 25 percent to 50 percent of future drilling locations would no longer be accessible under a 2,000-foot setback from occupied buildings. Based on an associated reduction in overall oil and natural gas production, the analysis predicted a range of average annual impacts over a 15-year period.

2014 Setback Study: Key Findings

In the 2014 analysis, the authors also attempted to forecast the impacts of a 2,000-foot setback beyond 15 years, for a total time horizon of 25 years. Negative impacts would continue throughout the entire 25-year period, with the deepest losses seen from years 11 to 15. Of all the setback studies reviewed, the 2014 analysis was the only one that attempted to estimate impacts beyond 15 years.

The 2014 analysis did not attempt to quantify a specific amount in lost tax revenues. However, the report estimated that oil and natural gas development generated $1.1 billion in local and state taxes in 2013.

2015: Updated Economic Assessment of Colorado Oil and Gas Setback Discussionvi

In 2015, CSPR along with the Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation and the Denver South Economic Development Partnership, known as the REMI Partnership, commissioned the CU Leeds School of Business to produce an updated and expanded analysis of a 2,000-foot setback from occupied buildings.

The analysis used CSPR’s updated REMI model, with new data on oil and gas production levels as well as underlying economic metrics for Colorado. It was expanded to estimate the impacts on personal disposable and tax revenues in addition to impacts on employment and state GDP. Also, the long-term impacts on employment and state GDP were measured over a 15-year horizon instead of 25 years.

Based on reduced new drilling and an associated reduction in overall oil and natural gas production, the analysis predicted a range of average annual impacts over a 15-year period:

2015 Setback Study: Key Findings

On tax revenues, the authors of the analysis produced a range of estimated annual impacts for the first five-year period under a 2,000-foot setback from occupied buildings: $214 million to $428 million in lost local and state revenue.

The authors of the report noted, however, that this initial estimate on tax revenue impacts excluded the first year of production from newly drilled wells and the impact of these production volumes on local property taxes and state severance taxes. This is significant, because newly developed oil and gas wells typically produce their highest volumes of oil and natural gas in their first year.

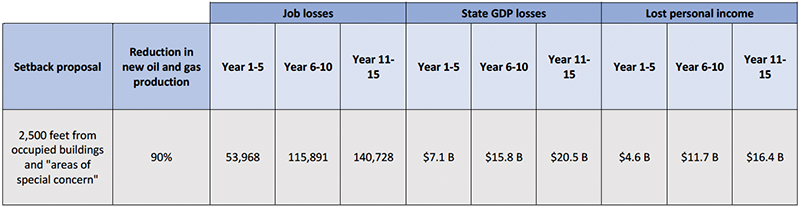

2016: Economic Assessment of 2,500-Foot Oil and Gas Setback Proposalvii

In 2016, environmental groups revised their approach to setback ballot measures. In addition to occupied structures, their proposed setbacks would also be applied to a list of other locations, including natural features found in lightly populated rural areas and uninhabited areas of the state.

After introducing ballot measures with a range of setback distances, the proponents moved forward with Initiative 78, which called for a 2,500-foot setback around occupied structures and a separate category of locations called “areas of special concern.” According to the text of the measure, an area of special concern:

“…includes public and community drinking water sources, lakes, rivers, perennial or intermittent streams, creeks, irrigation canals, riparian areas, playgrounds, permanent sports fields, amphitheaters, public parks, and public open space.”viii

Another provision of Initiative 78 would allow local governments to increase the 2,500-foot setback, but not decrease it. The ballot measure placed no upper limit on the distance that local governments could increase the setback.

In response to the new, broader application of the setback ballot measure, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources conducted a Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis of Initiative 78.ix The GIS analysis concluded:

- Approximately 90 percent of Colorado’s land would be unavailable for future oil and gas development

- In Weld County, the state’s top producer of oil and natural gas, 85 percent of land would be unavailable for future oil and gas development

- In the state’s top five producing counties (Weld, Garfield, La Plata, Rio Blanco, and Las Animas), 95% of land would be unavailable for future oil and gas development

To estimate the economic impact of Initiative 78, the REMI Partnership commissioned the CU Leeds School of Business to conduct its own analysis, using the State of Colorado’s GIS findings as a starting point.

Under CSPR’s direction and using the REMI model, CU Leeds estimated the impact of a 90 percent reduction in new oil and natural gas production due to the reduced number of available drilling locations under Initiative 78. The analysis predicted a range of average annual impacts over a 15-year period:

2016 Setback Study: Key Findings

The analysis did not attempt to quantify a specific amount in lost tax revenues. However, the report estimated that oil and natural gas development generated $1.2 billion in local and state taxes in 2014.

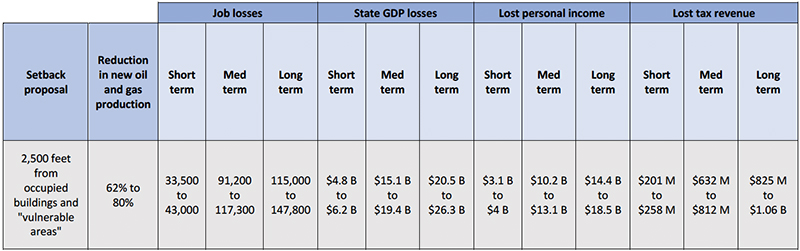

2018: The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of 2018 Proposition 112x

In 2018, environmental groups proposed another 2,500-foot setback ballot measure. When first proposed, it was called Initiative 97. After qualifying for the ballot, it became known as Proposition 112, and was ultimately rejected by voters in November 2018.

Proposition 112 was closely modeled on the 2016 setback ballot measure, with some changes. Those changes included exempting federal lands, reclassifying areas of special concern as “vulnerable areas,” and giving local governments authority to expand the definition of vulnerable areas beyond the list of locations provided in the ballot measure.

The Colorado Department of Natural Resources conducted a GIS analysis on the 2018 ballot measure, and despite the exclusion of federal land, the state agency concluded significant impacts for major oil and natural gas producing areas of the state:

- Approximately 85 percent of state and private land would be unavailable for new oil and gas development

- In Weld County, the state’s largest producer of oil and natural gas, 85 percent of state and private land would be off-limits, and 78 percent of total land area would be subject to an effective drilling ban

- Even with the federal land exemption, more than half the state’s total land area would be subject to an effective drilling ban

Using the REMI model, CSPR used the State of Colorado’s GIS findings as a starting point for an economic analysis of the ballot measure. The analysis was conducted with the REMI Partnership, whose members included Colorado Concern, Denver South Economic Development Partnership, the Colorado Bankers Association and the Colorado Association of Realtors. The methodology and findings of the analysis were also submitted for pre-publication review by subject matter experts – Dr. Ian Lange and Dr. Braeton Smith – at the Mineral & Energy Economics Program of the Division of Economics and Business at the Colorado School of Mines.xi

The analysis found that 89 percent of new oil production in Colorado, and 87 percent of new natural gas production, takes place inside the setback area created by Proposition 112. With new production no longer possible in these areas, the analysis explored two future scenarios where the oil and natural gas industry tried to recover – or displace – a percentage of the lost production through the use of horizontal drilling in other parts of the state.

The most optimistic scenario assumed 30 percent displacement would be possible. Under a less optimistic scenario, only 10 percent displacement would be possible.

After reviewing the impact of these restrictions on overall oil and natural gas production, CSPR used the REMI model to estimate the impacts of the 30 percent displacement and 10 percent displacement scenarios. Instead of the 15-year time horizon used in previous studies, the analysis of Proposition 112 examined a 12-year period, starting in 2019 and ending in 2030, and estimated impacts were produced for the short-term (2019), medium-term (2025) and long-term (2030).

2018 Setback Study: Key Findings

On the issue of employment impacts, CSPR found that 77 percent of job losses would occur outside of the oil and gas industry, in sectors such as retail, professional, scientific and technical services, healthcare, construction and local and state government. These effects were a result of “economic linkages” between the energy sector and the rest of the economy, “including the disruption to the industry supply chain, the loss of consumer demand from fewer jobs and lower income, and in lower investment in non-residential and residential capital and equipment.”

CSPR’s 2018 study on setbacks also explored the issue of tax revenues in much greater detail than earlier research efforts. The study found “[t]he direct loss in state and local tax revenue from new oil and gas activity, including from severance taxes, property taxes, income taxes, and sales and use taxes” would start in the range of $201 million to $258 million in the short term, rising to a range of $825 million to $1.06 billion in the long term.

Lessons learned for future setback studies

Studies produced on setback ballot measures since 2014 have produced a range of outcomes, all of which indicate significant and lasting negative impacts for the Colorado economy and for the tax revenues that fund essential services at the local and state level.

The magnitude of these impacts, however, have changed over time. This is the result of setback ballot measures evolving to cover larger areas of the state, increased availability of geographical data to quantify the impacts of setback ballot measures, and continued growth in the production of oil and natural gas in Colorado since the first setback ballot measures were proposed in 2014.

These trends offer several lessons for the next round of analysis of setback ballot measures in 2020.

- Geographical information

The first studies on setback ballot measures did not have the benefit of detailed GIS data. This changed in 2016, with the State of Colorado producing detailed maps and land area estimates based on the definitions of “areas of special concern” and “vulnerable areas.” These estimates played a central role in the debate over these ballot measures, providing policymakers and the public with a much clearer sense of the likely impacts.

However, there were still significant limitations to the data which should be addressed, if possible, in future studies on setback ballot measures. For example, in 2018, DNR officials said they were unable to obtain location data for several categories of vulnerable area, including public parks and public open spaces, and did not have location data for occupied structures in 11 of Colorado’s 64 counties. In another six counties, DNR was only able to access location data for occupied structures that was two years or more out of date.

In practice, this means the full reach of setback ballot measures has been underestimated. Therefore, future efforts to quantify the impact of proposed setbacks should be based on updated and more complete GIS data, to provide policymakers and the public with the best estimates possible.

- Expansion of 2,000-foot setback beyond occupied structures

The first studies into setback ballot measures – in 2014 and 2015 – dealt with a setback distance of 2,000 feet from occupied structures. Subsequently, setback ballot measures in 2016 and 2018 increased their distance to 2,500 feet, with a much broader scope that included many other locations besides occupied structures. This year, one of the proposed setback ballot measures brings back the 2,000-foot distance, but instead of occupied structures only, the setback would be applied to both occupied structures and a list of vulnerable areas.

In practical terms, this means the amount of land impacted and the number of drilling locations that would be unable to be developed would be much greater under today’s 2,000-foot setback ballot measure than then findings of the 2014 and 2015 studies would indicate. In addition to significant growth in oil and natural gas production since those studies were produced, the expanded application of the setback to vulnerable areas would also magnify the impacts significantly.

- Growing production and changing economics in the oil and natural gas sector

Initial research on setback ballot measures was based on 2013 production levels for oil and natural gas in Colorado. But energy production, and the economic activity associated with it, has increased significantly in Colorado since then.

For example, from 2013 to 2019, annual oil production in Colorado increased 183 percent, from approximately 66 million barrels per year to 187 million barrels per year. This increase occurred despite a significant fall in West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices, from an average of roughly $98 per barrel in 2013 to $57 per barrel in 2019, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

A similar trend, albeit less pronounced, has also taken place in Colorado natural gas production. Levels of production climbed 24 percent from 2013 to 2019, while average natural gas prices fell approximately 31 percent over the same timeframe.

These trends reflect improved efficiencies in the oil and natural gas sector, both in Colorado and in other states. Industry analysts have noted a major decline in so-called “breakeven” energy prices for oil and natural gas firms in recent years, as the industry has adapted to lower prevailing oil prices.xii In 2016, for example, WTI oil prices averaged just above $43 per barrel over the whole year, and started the year in the $20 to $30 per barrel range.

While some of the growth in oil and natural gas production may have been captured during the most recent round of research into Proposition 112, any examination of the impacts of a setback ballot measure in 2020 will likely need to work from an updated baseline. For example, 2017 was the last full year of production data before the publication of CSPR’s research into Proposition 112 in 2018. Between 2017 and 2019, Colorado oil production increased by 41 percent and natural gas production increased by 16 percent.

Understanding how Colorado’s oil and gas industry has adapted to changing energy prices in the past will also be important when building assumptions about how this sector of the economy will adjust to the impacts of COVID-19 and the recent price war between other oil-producing nations, which have together pushed the WTI price benchmark sharply lower since March 2020.

Conclusion

Reviewing research on past setback ballot measures provides useful insights into the likely impacts of the new setback ballot measures proposed for the 2020 election. The same review can also identify important lessons on the methods and assumptions used to estimate these impacts, and how they can be updated.

Current research on setback ballot measures, conducted since 2014, suggests a 2,000-foot or 2,500-foot setback around occupied buildings and vulnerable areas will have – at a minimum – significantly negative economic impacts on the state as a whole. In the short term, these existing studies provide a directional sense of the impacts of the latest round of setback ballot measures proposed for the 2020 election.

However, it should be noted that past research into setback ballot measures will not fully account for the impacts on the Colorado energy sector and the broader economy as they exist today. This research was conducted during a period of steady to robust growth in Colorado. It does not account for the sudden economic contraction our state is experiencing due to cumulative impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown and a sudden drop in energy prices caused by a price war between oil-producing nations.

Historically, Colorado’s energy sector has bounced back from sudden price declines by finding more efficient ways to produce oil and natural gas. In so doing, the energy sector has continued as an important source of jobs, tax revenue and economic activity for the State of Colorado in times of growth and in times of recession.

Therefore, in the current climate, setback ballot measures may pose a series of new questions, not just about the energy sector, but the recovery of the state economy as a whole. For example: If setbacks are dramatically increased, and Colorado energy production permanently declines, how much deeper will a possible recession be, and how much longer will it take for the Colorado economy to recover and return to growth?

The existing body of research can provide partial answers to some of these questions. However, new research that accounts for the economic challenges now facing the state, along with other developments, will be necessary to ensure voters have the best available information to judge the debate over setback ballot measures for themselves.

ENDNOTES

i Initiatives 173, 174, 175, 176 and 177 can be viewed at the Colorado Secretary of State’s 2019-2020 Initiative Filings, Agendas and Results page: https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/Initiatives/titleBoard/index.html

ii Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission: 2500’ Mandatory Setback from Oil and Gas Development. Available here: https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/library/Technical/Miscellaneous/Init_78_Proposed_2500ft_Setback_Assessment_Report_20160527.pdf

iii Common Sense Policy Roundtable COVID-19 Colorado Resources Station: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/covid19/

iv CSPR’s complete collection of energy studies, including research on setbacks, can viewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/research-issues/energy/

v The full study can be reviewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Economic-Impact-of-OG-Ballot-Initiatives-090814.pdf

vi The full study can be reviewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Colorado-Oil-and-Gas-Update-Policy-010616.pdf

vii The full study can be reviewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Colorado-OG-2500-Setback-Economic-Impact-Study-071116.pdf

viii Initiative 78 full text: https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/Initiatives/titleBoard/filings/2015-2016/78Final.pdf

ix Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission: 2500’ Mandatory Setback from Oil and Gas Development. Available here: https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/library/Technical/Miscellaneous/Init_78_Proposed_2500ft_Setback_Assessment_Report_20160527.pdf

x The full study can be reviewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CSPR_CO_Proposition_112_Report.pdf

xi The review letter from Dr. Lange and Dr. Smith can be viewed here: https://www.commonsenseinstituteco.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CSPR-Statement.pdf

xii Rystad Energy Ranks the Cheapest Sources of Supply in the Oil Industry, available here: https://www.rystadenergy.com/newsevents/news/press-releases/Rystad-Energy-ranks-the-cheapest-sources-of-supply-in-the-oil-industry-/