ABOUT THE TERRY J. STEVINSON FELLOWSHIP

The Terry J. Stevinson Fellowship was established in honor of Terry J. Stevinson, a founding board member of Common Sense Institute (CSI). Thanks to Mr. Stevinson’s continuing dedication to free enterprise these fellowships have been named in his honor.

The Terry J. Stevinson Fellowship is designed to spur thoughtful policy discussions and potential solutions regarding the many policy and economic challenges brought about by population growth in Colorado. Through a multi-year effort, CSI will work with two or more individuals with differing backgrounds on an annual basis to dive into one particular area concerning growth.

About the 2021 Fellowship

With an influx in the Colorado population over the last twenty years, housing affordability has quickly become a pressing issue in many parts of the state. While this is not an issue unique to Colorado and its major urban areas, it remains an important issue to maintain Colorado’s quality of life and economic competitiveness. That is why the 2021 Terry J. Stevinson Fellowship will be dedicated to researching the issues surrounding growth and housing.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

2021 Terry J. Stevinson Fellows

Evelyn Lim

Evelyn Lim is the Director of Policy and Research at the American Cornerstone Institute. She was most recently the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Regional Administrator for Region 8 which covers Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. In March 2020, she was detailed to Secretary Carson’s office to lead HUD’s coronavirus relief efforts and support the Secretary in his role on the White House Coronavirus Task Force. Prior to her appointment at HUD, she served as the Deputy Chief of Staff at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the third largest federal cabinet agency with over 240,000 law enforcement, military, and civilian employees.

Peter LiFari

Peter LiFari is the Executive Director of Maiker Housing Partners. As one of over 3,000 Housing Authorities across the country, Maiker works alongside other members from communities across the country to ensure housing needs are advocated for on a national level. Maiker, an owner, operator and developer of affordable housing communities in Adams County, CO, collaborates with other Housing Authorities to collectively work toward the overarching mission of the industry to create attainable and sustainable housing and communities for vulnerable families and individuals.

ABOUT COMMON SENSE INSTITUTE

Common Sense Institute is a non-partisan research organization dedicated to the protection and promotion of Colorado’s economy. CSI is at the forefront of important discussions concerning the future of free enterprise in Colorado and aims to have an impact on the issues that matter most to Coloradans.

CSI’s mission is to examine the fiscal impacts of policies, initiatives, and proposed laws so that Coloradans are educated and informed on issues impacting their lives. CSI employs rigorous research techniques and dynamic modeling to evaluate the potential impact of these measures on the Colorado economy and individual opportunity.

Common Sense Institute was founded in 2010 originally as Common Sense Policy Roundtable. CSI’s founders were a concerned group of business and community leaders who observed that divisive partisanship was overwhelming policymaking and believed that sound economic analysis could help Coloradans make fact-based and common sense decisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In acknowledgement and appreciation to our stakeholders who provided their time, talent, and expertise to us. You inspire us and we appreciate you immensely. Thank you all for the work you to do to house all Coloradans.

Heidi Aggeler, Managing Director and Co-Founder, Root Policy Research

Destiny Bossert, Lobbyist & Government Affairs Manager, Apartment Association of Metro Denver

Anthony Burke, President, Pinkard Construction

Jonathan Cappelli, Executive Director, Neighborhood Development Collaborative

Rich Cimino, County Commissioner Grand County

Brian Connolly, Otten Johnson/Colorado Housing Affordability Project

Bryan Cook, Executive Director, Construction Education Foundation

Scott Cox, Principal, SLC Advisors

Kimball Crangle, Colorado Market President, Gorman & Company

Dick Elsner, County Commissioner Park County

Mark Feilmeier, State Director, HUD

Andrew Feinstein, CEO & Managing Partner, EXDO Development Group

Katie First, Advocacy & Special Projects Associate, Colorado Counties, Inc.

David Flaherty, CEO, Magellan Strategies

Sarah Geis, Senior VP, Community Development Lending & Investing, Key Bank

Daphne Gervais, Legislative & Policy Advocate, Colorado Counties, Inc.

Alison George, Director, State of Colorado Department of Local Affairs, Division of Housing

Pete Gombert, Co-Founder & Executive Chairman, indieDwell

Jamie Gomez, COO & Deputy Director, CHFA

Drew Hamrick, General Counsel & Sr. VP of Government Affairs, Apartment Association of Metro Denver

Jeff Hopfenbeck, Co-Founder & CEO, Simple Homes

Bruce Hoyt, Impact Housing Advisor, indieDwell, former SVP at Gary Community Investments

Brett Jacques, Associate Principal, Van Meter Williams Pollack

Matt Joblon, CEO, BMC Investments

Carl Koelbel, COO, Koelbel Co.

Greg Krause, Principal and Co-Founder, K2 Residential Solutions

Hunter Kurtz, former Assistant Secretary HUD, GateHouse

Elizabeth Lawrence, County Commissioner Summit County

Ted Leighty, CEO, Colorado Association of Homebuilders

Paul Major, President & CEO, Telluride Foundation

George Marlin, County Commissioner Clear Creek County

Rachael Minore, Aide to the Board of County Commissioners at Adams County Government

Aaron Miripol, President & CEO, Urban Land Conservancy (ULC)

Jennifer Newcomer, Research Director, Colorado Futures Center

Marla Novak, Director of Government Affairs, HBA Colorado Springs

Steve O’Dorisio, County Commissioner Adams County

Kristian Peterson, Managing Director, Catalyst Opportunity Funds

James Roy, Executive Director, Denver Metro Community Impact

Liz Smith, County Commissioner Gunnison County

John Swartout, Executive Director, Colorado Counties, Inc.

Mike Zoellner, Managing Partner at ZF Capital, Director at Colorado Apartment Association

Executive Summary

The housing affordability crisis is reaching a breaking point in many markets across Colorado. May 2021 set a record-low number of home listings in the Denver Metro at just 2,075 compared to the monthly average of 15,563, and the 12-month increase in the price of the average single-family detached home sold grew by 29%.

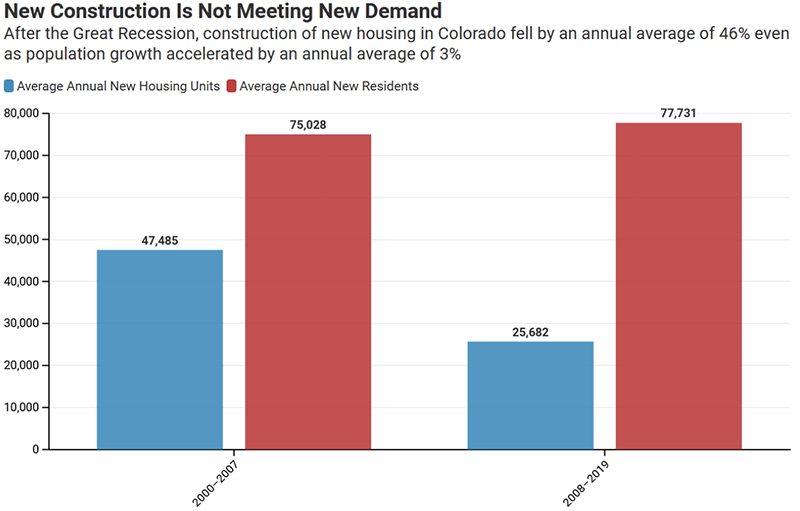

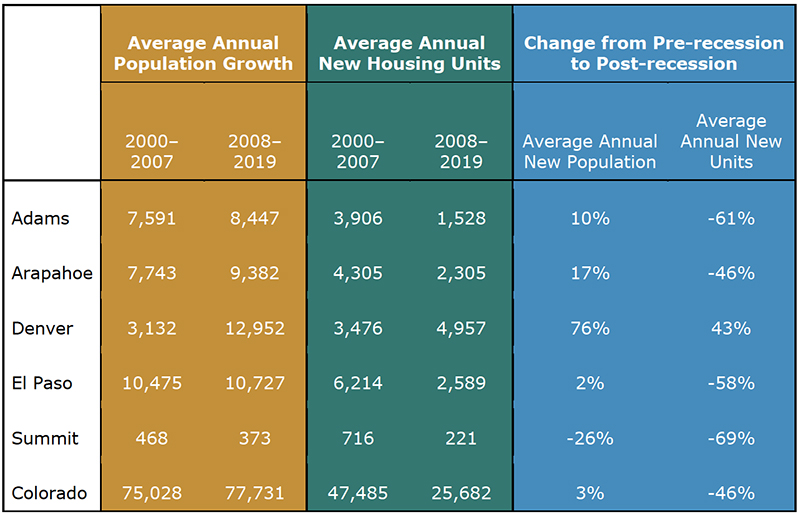

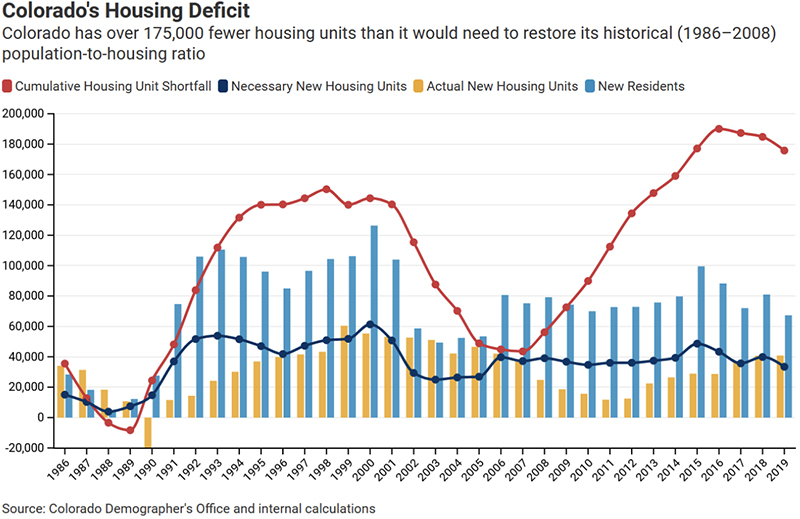

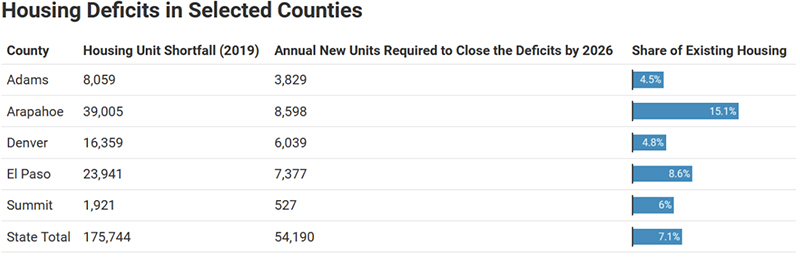

However, this is not a new problem. The average annual number of new homes built every year in Colorado since the 2008 financial crisis is 46% lower than the annual average in the 8 years leading up the recession. If Colorado were to return to the average housing to population ratio between 1986 and 2008 it would require an additional 175,000 housing units across the state today. To close that gap and meet the future population needs Colorado will need to develop 54,190 new housing units annually over the next five years. Despite housing being a foundational human need, the cost burden of housing has threatened too many Coloradans’ way of life.

We need transformational changes that can bridge the divide we have in our communities that has led to a broken housing development value chain. The conclusions of this report offer practical solutions to break us from the status quo. While they require bold action from our state’s housing leaders both in the public and private sectors, the time to act is now.

The research and policy ideas of this paper were informed by over 40 conversations and interviews with housing experts across Colorado. We went into each interview with open minds and listening hearts.

Our methodology was simple: ask the questions no one else is asking. What are the force multipliers? Where are the rabbit holes? Where are they doing it right? What is no one talking about but needs to be part of the conversation? If you had the magic wand for the day, how would you fix this issue? The conversations around these questions shaped our thoughts, influenced our recommendations, and in some cases, changed our minds. The following guiding principles serve to ensure conversations around reforms recognize we share a common interest in seeing positive change.

Colorado Housing Development Guiding Principles

LET US:

-

- Be honest with ourselves – and do away with binary constructs that distill people into characters. No more “us vs them”, “good vs bad”, NIMBY vs YIMBY. Simply, us as Coloradans, in need of an affordable home.

- Embrace growth – a vibrant, growing economy, supported by a healthy housing supply, benefits us all; increasing our tax base, sustaining our communities’ basic needs.

- Reform the popular notion that all development, most specifically affordable development at or below 60% AMI, must pay its own way.

- Be proportional, equitable, and inclusive.

- Acknowledge that the private market will not create deeply affordable units at the scale required on their own, nor will inclusionary zoning tools alone accomplish this in our current construct.

- Embrace new building methodologies to increase productivity and growth.

- Act with a sense of urgency and purpose.

Building from our guiding principles, stakeholder conversations and our collaborative research, we offer a sequence of reforms that can disrupt the broken system holding back housing supply. These solutions are distilled into ideas that work as told by our stakeholders, force multipliers that could bring about a change to the development landscape, and a Colorado Housing Development Blueprint that could lead to transformational change.

Ideas that Work and Force Multipliers

We have curated a list of the most recommended policies discussed during our stakeholder engagement and subsequent research, for our state and local governments to consider in addition to our own recommended policies. We passionately reiterate the sobering fact that all the tools in the world won’t make a difference if we don’t first change our entire mindset when it comes to housing development and growth. The policies below are only as effective as we allow them to be and any one of them alone will not solve our problem.

Ideas that Work, If We Let Them

These options for policymakers to consider come from a broad range of housing professionals in our state; the people doing the work. We have seen some of these ideas in play in other cities and so we dug into how they worked and what could work differently in our state.

- Prioritize the Use of Public Property for the Development of Mixed-Use Affordable Housing

- Prioritize Homes Over Parking Spaces and Create Greater “Use By Right” Zoning Overlays

- Unlock Large and Non-Traditional Sites for Housing Development (e.g., Malls and Large Retail Sites)

- Utilize Community Land Trusts to Create and Maintain Affordable Home Ownership

- Allow for Accessory Dwelling Units – An Important Step Towards Standardization

- Expedite the Review, Permitting and Public Hearing Scheduling Processes for Qualified Projects

- Reduce or Waive Impact Fees for Qualified Projects

- Introduce Other Forms of Capital in Addition to Low Income Housing Tax Credits

Force Multipliers

Common sense means practical and pragmatic. But, when applied correctly, it can also be a force multiplier. We were not restricted by ideological constraints. Because we want solutions that unleash the talent and skill we possess in our state, we released ourselves from any tribal loyalties and trusted one another to pressure test and think through big ideas. We are asking our leaders and housing partners to do the same and we have some ideas to share.

- Implement a uniform statewide building code to kickstart productivity gains

- Expand pathways to careers in construction

- Scale the Telluride Foundation Rural Homes: For Sale, For Locals pilot project

Transformational Change

We have the ability to jump start progress using the funds of the American Rescue Act. This influx of cash from the federal government can make a generational impact on a problem that will last for decades if we don’t act now.

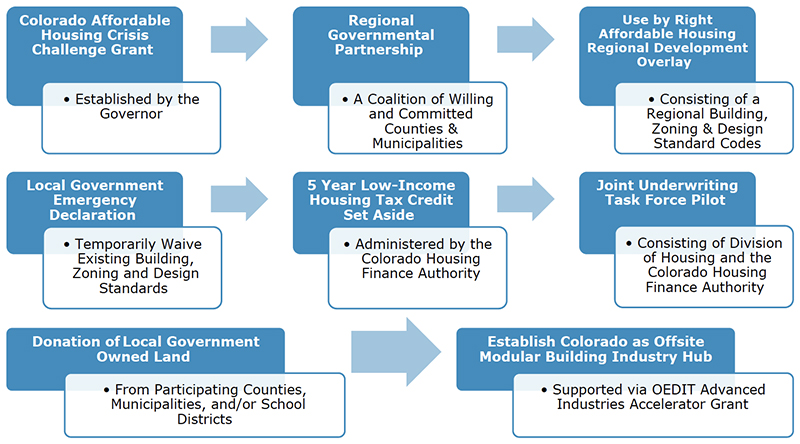

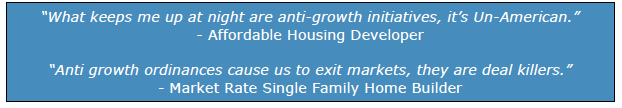

The Colorado Housing Development Blueprint

The solutions we offer are aimed at increasing housing opportunities for our fellow Coloradans. They would be all for naught with the implementation of anti-growth measures. We view no growth ordinances as the biggest threat to affordable housing in Colorado, and our state legislature should act to eliminate these threats. These measures negatively impact any and all development which has deleterious effects on our economy and infringes on individual property rights which is just plain un-American.

The events of the past 15 months have caused seismic shifts in how we view and see the world, each other, and what we value most. They have also further stressed our already broken system of housing development and caused unsustainable pressure on affordability. With a little ingenuity, collaboration, and good old pioneering spirit (and of course funding), the Blueprint we designed could make a measurable impact on our housing challenges and be on the forefront of transformative change in the housing industry.

Introduction

It’s a universal fact that everyone needs a home, or is it? Housing is a human right, or is it? Housing is infrastructure, Housing is healthcare, Housing is wealth, Housing is opportunity. Housing is, Housing is, Housing is… Yet here we are in the throes of the worst housing crisis our state and nation has faced since the end of World War II with no meaningful consensus on how to effectively solve the issue. Median home prices across the state are experiencing double digit month over month increases, over seventy percent of home sales in 2021 have experienced bidding wars with the majority closing for tens of thousands of dollars over list price. If housing is so critical to our health and well-being as humans, then why are we here? Why are so many Coloradans priced out of an affordable place to live, be it a rental or an owner occupied home? Why do so many Coloradans oppose new developments in their communities? How can we break this cycle of conflict that has led us to woefully miss the mark year after year of new housing creation here in Colorado, to meet the fundamental need of our growing population?

The issue of housing affordability in Colorado is not a new issue. Over the last decade we have not been building enough homes to meet the demand for housing. As more and more people are driven to the Centennial state, whether for the moderate climate, the outdoor activities, the laid-back lifestyle, or our diverse and strong economy, the state continues to attract more people who want to make Colorado their home. Despite the pandemic, people are still moving, and many are moving here, according to a recent study that ranked Denver as the 5th most popular moving destination,[i] behind Phoenix, Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta. The same study ranked the state as a whole 8th for inbound moves nationwide.[ii] And over the last year, as people became disillusioned over the tight and overcrowded cities of the coast, and as pandemic “work from home” turned into “work from anywhere,” 2020 saw an influx of individuals moving from high-cost states. They were flush with cash and ready to buy; exacerbating an already tight housing market, driving prices up, and creating a frenzy in almost every housing market in the state.

In Denver, residential homes in every segment are flying off the market within days, not weeks. In May, median home prices rose 22.81% year over year. And the average single family detached home in the Denver metro region closed in May at an all-time high of $700,559, a jump of over 29% from an already competitive year prior. Resort mountain towns are likewise experiencing dramatic surges in demand for both primary and secondary home buyers. Many buyers are foregoing inspections and other processes meant to protect buyers, while still making aggressive offers that are $20,000 to $100,000 or more above sales price. Who can afford to make these aggressive offers? Desperate Coloradans, institutional and cash buyers.

A 2017 poll from Colorado Mesa University ranked housing as the number one issue facing Coloradans. A more recent online survey conducted by Magellan Strategies of Colorado voters found that 74% consider affordable housing to be a problem in their community. There isn’t a news publication in the state that doesn’t cover the housing crisis on a weekly basis, if not daily.

People looking for homes are frustrated and trapped. And what is clear is that we aren’t building enough housing. Colorado must provide housing for a diverse set of residents, and thus far we would give ourselves a failing grade in this area. There are ongoing discussions from the state capitol to the kitchen tables about housing affordability. And there is no dearth of opinions on policy interventions that should be undertaken to alleviate the problem.

So where does that leave us? Our goal with this report was to provide an overview of available policy interventions, provide our recommendations on what could be done, along with what should be done, and do it all in a way that makes sense to everyone. Because this is a problem that affects all Coloradans; whether you are searching for a home, fighting off eviction, couch surfing, living in your car, a tent, or reading this with heartfelt concern. If we are to solve this crisis we must put aside ideology and political labels to focus on the heartbeats that we work to house.

Methodology

To make some sort of sense of the chaos, we engaged a diverse group of stakeholders to search for root causes, identify systemic change drivers and break through the noise that divides Coloradans on this issue. We wanted to talk to the people on the ground, doing the work, to hear their unfiltered thoughts on what needed to be done to get us out of this housing deficit. What questions are not being asked? Or more importantly what questions are being asked but the answers are embargoed, sequestered, lost to the broader debate? So, we went to the experts in the community that represented voices across the housing continuum and communities across the state.

Beginning in late February through June we met with over 40 industry leaders encompassing elected officials, developers, general contractors, lending institutions, state and local government professionals, neighborhood collaboratives, community activists, offsite builders, land use and planning experts, investors, industry associations, and policy professionals and practitioners at every state, local and federal level. What we found was a dedicated, passionate, vulnerable and eager audience; each focused on doing their part to house Colorado, and to do so to the best of their abilities. And before we get too far, we acknowledge and appreciate the time and input these people have given us. Their insights have shaped our thoughts, influenced our recommendations, and in some cases, changed our minds.

We went into each interview with open minds and listening hearts. The crisis that is plaguing our communities is not a new development and took years in the making. We hear a chorus of voices throughout the state all calling to solve the problem. But what we do not hear is the consensus on how to get there, or frankly, common sense solutions.

Our methodology was simple: ask the questions no one else is asking. We found that regardless of the stakeholder being asked, it launched us into a wide-ranging conversation from people who were deeply committed to housing people, building communities, and solving problems in our state. So we kept asking. What are the force multipliers? Where are the rabbit holes? Where are they doing it right? What is no one talking about but needs to be part of the conversation? If you had the magic wand for the day, how would you fix this issue?

Asking the right questions is important. And when you get a couple of dedicated and concerned housing professionals on a zoom, the conversation can be wide ranging. But even more important than asking the right questions, is listening to the answers. Coming from different parts of the ideological spectrum, we came with different viewpoints and often our own answers to the questions we were asking. Yet, if we had the obvious answers, what would be the point of even asking other experts? We engaged this group of experts to hear their inputs, rather than be converted to one viewpoint or the other. Because we acknowledge we didn’t necessarily know the answer, any idea was legitimate, all concerns were rational, and even contradictory perspectives could lead us to capitalize on the tension between views that led to valuable insights. We asked the hard questions which led us to engage in trade offs and engaging with people with different viewpoints allowed us to improve, refine, and pressure test our recommendations.

Time and time again we left these conversations invigorated, optimistic yet bound by the realities of our constraints. Each expert illuminated a systemic fracture in the delivery model, each expert shared how well intended stakeholders, in all roles, in an attempt to address a concern or an ideal more often than not, exacerbated the root problems as opposed to moving towards meaningful change.

While many expressed frustrations they were quickly transformed into opportunities inspired by a sense of genuine urgency. A shared desire for bold, sweeping change permeated throughout each conversation. Eager to share ideas as to what trade offs they would gladly debate and ultimately greenlight should the opportunity to empower true outcomes present itself.

Take this quote from an affordable housing developer: “We’re losing the fight, we need to bring the hustle!”

Or this quote from a market rate and affordable housing developer: “This is our generational problem to solve.”

So How Did We Get Here in the First Place?

What became readily apparent was the extreme lack of equilibrium in our housing continuum. When we say extreme, we mean irrational. Coming out of the great recession, the state of Colorado stopped building. With a supply chain dependent on abundant local skilled labor, cheap commodities such as lumber and resins, low interest rates, abundant credit and a traditional pool of buyers who will put 10 to 20 percent down on their home via a standard mortgage lender, any one disruption can impact the cost and availability of housing and disproportionately affect affordable housing. Breaking down the complexities in a manner that is easy to understand and that doesn’t come off as pushing an agenda is difficult.

What became readily apparent was the extreme lack of equilibrium in our housing continuum. When we say extreme, we mean irrational. Coming out of the great recession, the state of Colorado stopped building. With a supply chain dependent on abundant local skilled labor, cheap commodities such as lumber and resins, low interest rates, abundant credit and a traditional pool of buyers who will put 10 to 20 percent down on their home via a standard mortgage lender, any one disruption can impact the cost and availability of housing and disproportionately affect affordable housing. Breaking down the complexities in a manner that is easy to understand and that doesn’t come off as pushing an agenda is difficult.

One industry expert stated it clearly: “Housing is highly complex and most good natured folks don’t have the time to make sense of it all – threats become easily overblown.”

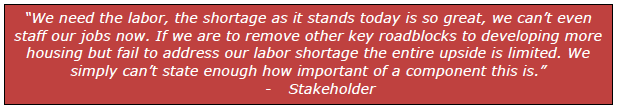

Where we find ourselves today is akin to fighting a war on multiple fronts in the winter, with dwindling food and supplies. Labor is significantly constrained and aging. Families are reluctant to support, let alone encourage, their children to go into the construction skilled labor trades despite strong prevailing wages and low barriers to entry. Builders are practically rolling out the red carpet to train and hire workers. Commodities are scarce due to multiple factors including the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters that have closed mills, tariffs on Canadian imports, and the misforecasting of the sheer demand for home remodeling in mid to late 2020.

Concurrently, Coloradans have grown fearful of housing development and we are letting each other know it. Social media has expedited the ability for community members to organize and express their feelings at a pace and tone that exacerbates the divides in our thinking on this fundamental need of ours. Take as an example the divisive and dangerous tribalism of Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) vs. Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) – a classic example of what author Amanda Ripley calls High Conflict, which is present in all major human conflict – that has spiraled out of control.

Ripley describes how quickly disagreements can turn toxic if we are not tuned into the warning signs, “High conflict can start small, but it becomes all consuming and has a life of its own. It usually is an us-versus-them conflict, but it can be about anything. What happens is our brain behaves differently. We start making significant mistakes about each other and the opportunities. And, eventually, everyone suffers to one degree or another. And everything we do to try to end high conflict usually makes it worse.”[iii] Ripley goes on to share that once groups become entrenched, compromise becomes very challenging. “We know from decades of research that anytime you sort humans into two oppositional groups, they will start behaving badly and favor the people in their group.”

Ripley describes how quickly disagreements can turn toxic if we are not tuned into the warning signs, “High conflict can start small, but it becomes all consuming and has a life of its own. It usually is an us-versus-them conflict, but it can be about anything. What happens is our brain behaves differently. We start making significant mistakes about each other and the opportunities. And, eventually, everyone suffers to one degree or another. And everything we do to try to end high conflict usually makes it worse.”[iii] Ripley goes on to share that once groups become entrenched, compromise becomes very challenging. “We know from decades of research that anytime you sort humans into two oppositional groups, they will start behaving badly and favor the people in their group.”

High conflict does not stop in our social media interactions. Community public hearings, a necessary and integral part of the entitlement process, often devolve into theaters of High Conflict, or us-versus-them conflict, across Colorado. What should be routine reviews of housing development proposals have become intense, often contradictory, and deadlocked disagreements. Well-meaning, good-hearted people who legitimately fear the impacts of housing development on their lives share concerns about the potential for tragedy be it in the form of traffic fatalities, increases in crime that threaten their physical safety, and fears of economic ruin via plummeting property values, which they see as the very foundation of their fiscal stability. Housing advocates, if in attendance, engage and counter with vigor, sharing their heartfelt grievances regarding systemic racism, oppression, wage and income inequality, and gentrification. Often, the only voice in support of the development is the developer, whose financial stake in the project makes them poorly suited to make the case in other’s eyes. Many expressed exhaustion, doubtful of the effectiveness of our current state of polarization – one community organizer framed it as such “NIMBYs and YIMBY’s are overrepresenting their positions – most people feel powerless.”

High conflict does not stop in our social media interactions. Community public hearings, a necessary and integral part of the entitlement process, often devolve into theaters of High Conflict, or us-versus-them conflict, across Colorado. What should be routine reviews of housing development proposals have become intense, often contradictory, and deadlocked disagreements. Well-meaning, good-hearted people who legitimately fear the impacts of housing development on their lives share concerns about the potential for tragedy be it in the form of traffic fatalities, increases in crime that threaten their physical safety, and fears of economic ruin via plummeting property values, which they see as the very foundation of their fiscal stability. Housing advocates, if in attendance, engage and counter with vigor, sharing their heartfelt grievances regarding systemic racism, oppression, wage and income inequality, and gentrification. Often, the only voice in support of the development is the developer, whose financial stake in the project makes them poorly suited to make the case in other’s eyes. Many expressed exhaustion, doubtful of the effectiveness of our current state of polarization – one community organizer framed it as such “NIMBYs and YIMBY’s are overrepresenting their positions – most people feel powerless.”

Local officials, leaders and staff feel duty bound to listen, engage and often intervene. Those in support of housing development have grown tired, frustrated with the consistent resistance to what feels like any and all development projects – especially those that are affordable housing or that house formerly homeless community members. One developer simply stated “all we want, all we need, is predictability.”

One participant expressed a well-intended climate change “green initiative” as such: “If you want a novel requirement that is a new, emerging technology, with little to no competition amongst vendors which creates no economies of scale, it’s going to be expensive, contrary to what your consultant is telling you, and to make it worse, you refuse to offer an offsetting financial incentive or funding mechanism to support it, guess what – the end user is gonna pay for it, that’s the tenant, the renter, the owner, and if you are to survive as an owner you’re going to understand how to best pass on that cost.”

One participant expressed a well-intended climate change “green initiative” as such: “If you want a novel requirement that is a new, emerging technology, with little to no competition amongst vendors which creates no economies of scale, it’s going to be expensive, contrary to what your consultant is telling you, and to make it worse, you refuse to offer an offsetting financial incentive or funding mechanism to support it, guess what – the end user is gonna pay for it, that’s the tenant, the renter, the owner, and if you are to survive as an owner you’re going to understand how to best pass on that cost.”

A common response following a critique of this type is from a market and affordable rate developer: “I hate that I have to choose between the environment and affordability – but we have few viable choices.”

As Coloradans, we find ourselves in a classic binary trap where we’re struggling to get out but we feel we have no options. The truth, however, is that we actually have many highly impactful opportunities, and we are already using many of them. But they cannot work in a vacuum; no one policy alone, or two, frankly, can save us. The biggest force multipliers require something greater of us – something rare, something fraught with risk: servant leadership, driven by the transformational power of vulnerability. We have to each admit where we have gotten it wrong as much as where we’ve gotten it right.

As Coloradans, we find ourselves in a classic binary trap where we’re struggling to get out but we feel we have no options. The truth, however, is that we actually have many highly impactful opportunities, and we are already using many of them. But they cannot work in a vacuum; no one policy alone, or two, frankly, can save us. The biggest force multipliers require something greater of us – something rare, something fraught with risk: servant leadership, driven by the transformational power of vulnerability. We have to each admit where we have gotten it wrong as much as where we’ve gotten it right.

While discussing vulnerability and a willingness to compromise, one market rate investor and land use expert expressed it as such: “It’s time that each of us engage with our tribes and broker deals amongst our factions first, so that we can compromise with others – we have no other option but to compromise.”

So where are we going astray? Where have we lost the path? Throughout the entire housing continuum, we need to start working together towards a common goal. The Governor, state and local officials, Fortune 500 CEO’s, Foundations, Chambers of Commerce, Universities and Hospitals – suit up, we’re all on the team. Vulnerability – we need more of it, our current approach is simply not working, it’s not that we don’t have the tools, it’s not that we’re lacking an understanding of the need for affordable housing, it’s our reluctance to accept that we need to radically change our entire approach to how we view, discuss and facilitate the development of housing, and it starts with leadership.

One interviewee who is an expert in impact investing feels that Coloradans are ready for systemic change because of the unique nature of our state politics, something missing in other states, “Colorado is the perfect proving ground – we collaborate across partisan lines, we place our egos aside, we can lead with hope.”

One interviewee who is an expert in impact investing feels that Coloradans are ready for systemic change because of the unique nature of our state politics, something missing in other states, “Colorado is the perfect proving ground – we collaborate across partisan lines, we place our egos aside, we can lead with hope.”

We are living in a period of enormous change. Housing is deeply personal. Yet we cannot allow our housing policy to be ruled by emotion and feelings, unless, that is of course, we don’t want to get anything accomplished. What’s needed is leadership. Much can be said about the qualities of a great leader. We all have personal experience in this. We either know by having a great leader in our life, or we know what qualities a terrible leader in our life does not have. One characteristic of great leaders is decisiveness. Great leaders understand how to balance emotion with reason and make decisions that positively impact their employees, customers, stakeholders, organizations and ultimately themselves. As author Simon Sinek teaches us, “Leaders Eat Last.”[iv] Making good decisions in difficult situations is no small feat because these types of decisions involve change, uncertainty, anxiety, stress, and sometimes the unfavorable reactions of others.

Leaders make hard choices. And we are asking for hard choices to be made. Amidst the many priorities of our state, housing must be one of them, if not the priority. All too often people pay lip service to housing as a priority. But through actions and policy decisions we see otherwise. The only real preference is revealed preference. One can see what actual preferences are made by people by observing their actual choices. When we are discussing housing, we see this in the policy choices our leaders make; often choosing options or creating regulations or laws that make projects virtually impossible to build.

As economist Thomas Sowell has famously said, “There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs.” So the real question becomes, what are the trade-offs for the policies we implement? Housing affordability is a crisis in our state; at every end of the housing continuum, except perhaps if you are lucky enough to be in the luxury home category. Most people in Colorado, whether you are searching for a home to rent or own or just on the sidelines, agree: we are in a crisis. Yet we don’t treat it like a crisis. We continue to focus on single policy issues in a vacuum without regard to whether policies work together, in tandem, or assuming that they just don’t.

As economist Thomas Sowell has famously said, “There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs.” So the real question becomes, what are the trade-offs for the policies we implement? Housing affordability is a crisis in our state; at every end of the housing continuum, except perhaps if you are lucky enough to be in the luxury home category. Most people in Colorado, whether you are searching for a home to rent or own or just on the sidelines, agree: we are in a crisis. Yet we don’t treat it like a crisis. We continue to focus on single policy issues in a vacuum without regard to whether policies work together, in tandem, or assuming that they just don’t.

What are the trade offs we are making in our state when it comes to housing policy. There are many, just as an example:

- When we choose parking over housing development

- When we choose lower density over housing development

- When we choose antiquated zoning regulations over housing development

- When we choose agendas over housing development

First, let’s begin with the acknowledgement that these can all be legitimate aims. But we can’t have all the cake, at least not all at once. It’s an inexorable mathematical reality, albeit complicated and complex as it is. However, given the realities of funding, time, etc., we must make choices; we must make trade offs. Given the crisis that we have been arguing over the last several years, we believe the answer should be that housing is our priority. Our commitment to housing should be shared by our leaders as a top-level priority that should not be subsumed by other priorities. And while we call on our political leaders to make housing a priority, we acknowledge that people across the development ecosystem share the responsibility for change, that trade-offs must occur at every level, and collectively we must come to a resolution for the benefit of all Coloradans.

Now that doesn’t mean housing is a priority to the exclusion of all else. But what it does mean is that we must prioritize housing and the choices and actions we take must reflect that actual preference.

We fellows call on our leaders at all levels to declare our housing shortage and subsequent housing affordability crisis a state priority. It must be clear to all Coloradans that the time for confusing symptoms for causes is over, the time to address the root causes is now. We simply cannot afford to persist in our current construct. We are frighteningly aware of the past, current and future outcomes should we remain wedded to our current ways.

We are not building enough housing…

We are not building enough housing…

The housing that gets built is the housing that we allow to be built.

We can change our trajectory if we so choose to address the systemic drivers precluding the development of affordable housing for all Coloradans.

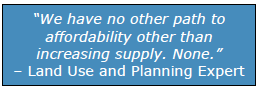

One land use and planning expert echoed this blunt root cause: “We have no other path to affordability other than increasing supply. None.”

Let us say it again – we are not building enough housing in the suburbs, we are not building enough housing in our cities, we’re not building enough entry-level, single-family homes, often referred to as starter homes, and we are not building enough affordable housing because we have not aligned our actions to our aspirations. The Governor should set this strategic priority and should set a statewide housing development goal, benchmarked to current and future demand, with a direction to the state legislature, state agencies, counties, municipalities and political subdivisions to join him in this priority.

So what would make this any different than past attempts? How can we Coloradans accomplish what seemingly no other state has in our national affordable housing crisis?

Let’s start by looking at the data.

So Just How Bad is Our Lack of Housing Supply? It’s Terrible, We Shouldn’t Sugarcoat It

Colorado is growing – like it or not, people continue to move here. We, as fellows, hope they continue to do so. We love Colorado and believe that our great state is fueled by our growth and we should embrace this fact. Colorado has added over 1.5M residents over the last two decades – with the state demographer’s office forecasting Colorado to reach 5.7M residents by the end of 2021. This growth rate places us amongst the top gaining states in the country and the pace is not expected to subside with our forecasted net in-migration averaging 51,393 new Coloradans a year over the next decade.

So are we keeping pace with our population growth in regards to new housing creation? Let’s evaluate the total housing units created in Colorado with a focus on the past two decades from 2000 to 2019 using information from the US Census and the state demographer’s office. It is here where we can see the compounding challenges of low housing unit creation in any given year, or even worse multiple year periods, creates – which has plagued our state ever since.

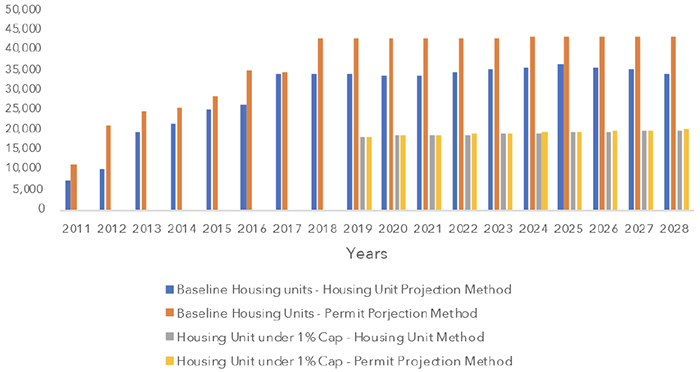

The high-water mark for housing units created in Colorado is 1972 with a healthy 65,664 units; a level we’ve not come close to any year since. In 2001, we created 55,007 units, and thanks in large part to consistent housing creation, for the first eight years of the decade we created more new homes on average per year, 38,558, than we averaged yearly in net in-migration, 36,804. However, the Great Recession created a gap from which we continue to experience the ramifications.

The Great Recession obliterated the housing development market, in the year 2008 we built 18,998 homes, a reduction of 35.5%, compared to 2007 when we built 29,454. But wait, it gets worse when we compare 2008 to the average from 2000 to 2007 of 44,653 homes built per year, representing a reduction of 57.45%. Okay, so that’s concerning but wait again, the bleeding continues. In 2009, we built 9,355 units, representing a reduction of 79%. Another way to frame the severe impact of the Great Recession on housing development is that over the next five-year period from 2010 to 2014 we averaged 20,921 units created a year, a reduction of 53% from our pre–Great Recession average.

While this severe reduction in annual housing creation was playing out, our population growth continued throughout the Great Recession; families continued to have children and people continued to move to our state. From 2007 to 2014, we added a total of 322,567 Coloradans, averaging 40,321 a year. Yet during that same time period, we only created 162,416 homes. Doing a simple one to one ratio, that would mean a shortfall of 160,151 units.

So how do we make sense of our housing supply needs? Do we require a one to one ratio each year of housing creation to net in-migration? How can we create annual targets for our cities and state to build towards, and do so consistently? To evaluate housing supply and demand conditions, Freddie Mac utilizes a formula consisting of the total number of housing units in the state, static estimates of housing demand, and net in-migration impact on the state.[v] To ascertain the demand for housing, Freddie Mac utilizes two components: long term vacancy rates and the target number of households. States with strong net in-migration, low vacancy rates and low housing starts, have a shortage of homes. As of 2018, Colorado per this measure has the fourth worst housing shortage behind only Washington D.C., Oregon, and California.

Freddie Mac concludes that the main drivers of our housing shortage is years of under building, exasperated by our strong state economy attracting consistent net in-migration, a shortage of available construction labor, land use regulations, restrictive zoning policies preventing the creation of supply, oppositional community interests, and a shortage of land. Of late, to compound the existing systemic challenges is the rapidly increasing cost of raw materials such as lumber which has experienced a 300% increase in price. But their most telling concern relates to the types of homes not being built – entry level single family homes. With Millennials now entering their prime home buying years, focused on purchasing a “starter home” the supply and demand imbalance will continue to persist, exasperating our current crisis. Presently, millennials account for more than half of all new mortgages.[vi] However, with a rise in both unemployment and housing prices, affordability remains the largest roadblock to prospective millennial homebuyers. How bad can it be, you ask? You’ve heard this plea before and everything works out just fine – I mean, every housing market cycle is tough right? Shouldn’t today’s buyers suck it up and stop complaining, save 20% of the purchase price as a down payment, buy what they can afford, where they can afford it, that’s what every generation deals with. Ahh… not this time around, not in this market, not in our state.

A crisis requiring a declaration by the Governor? Hyperbole? Clickbait? We wish that were the case, we surely do not want to be the harbingers of this desperate message, but the facts do not lie. Case in point, the Denver Metro Real Estate Market Trends Report June 2021 which showcases data from May of 2021.[vii]

- The average home sale (single-family detached) in Denver: $700,559 representing a year over year increase of 29.25%

- This has been made possible due to only 2,075 active listings (detached and attached). When compared to the seasonal average of 15,563 (1985-2020) an eye popping, gut turning reduction of 86.6%

- The spring buying season is especially telling. The month of May has traditionally been one of the strongest for month over month listings of homes for sale in a given year with an average increase of 8.11%. In May of 2021, we experienced a meaningful decrease of 20%, the largest on record and the only year we have experienced a month over month decrease in May since 2000, which was of a far smaller in impact at 3.15%

- The cost of lumber has increased 300% since April 2020. Resins, concrete, and steel are increasing at a likewise alarming rate.

- Denver has now experienced their first home lot auction sale – something previously thought of as exceedingly rare.

Colorado, whether in the front range, the high country, or the western slope, is experiencing a severe housing supply crisis. Our cities and counties struggle to create a policy environment that supports the creation of affordable housing options for their growing populations; costs rise, frustration mounts, and all Coloradans suffer. This lack of existing housing stock, exacerbated by the housing development lull during and after the Great Recession, coupled with local land use and zoning regulations that make developing housing more expensive than in generations past, has hampered our ability to keep pace with net in-migration. Barring a significant change in net in-migration, we simply have no precedent that gives us confidence that we can build the amount of housing units annually to meet the existing demand; let alone create more slack in the system by producing the units we need to recapture from the lost years of the Great Recession without wholesale change. But all hope is not lost. We can reverse the trends of note – if we’re willing to compromise and make tradeoffs. All of us, elected officials, planning commissioners, developers, community members, advocates, are required to change our current entrenched ways.

Take for example how we discuss our current state of affairs. The data demonstrates that we are not building enough housing. Yet we Coloradans are chafing against 40,000 housing starts a year; proclaiming that we are in a “Housing Boom” and questioning how we can support this unfettered growth. We see it in print and in our gathering spaces; this is detrimental rhetoric based on emotion rather than facts, setting expectations that our current amount of housing development annually is too much, when in fact it’s not nearly enough. How can we expect our fellow Coloradans to not react in opposition to housing development when our leaders tell them that our current housing development is not sustainable, or is not “smart growth,” or is too costly for localities to support in the form of local government infrastructure? Somehow, we’ve gotten it all mixed up and we’ve abandoned the key methodologies we’ve deployed historically to build and grow our cities to meet the needs of our citizens – those here and those we hoped to attract. Without citizens, without employers to support them, our local governments’ tax bases are constrained and our cities suffer. Why are we so oppositional to facilitating the creation of housing – what exactly are we trying to accomplish?

As the data demonstrates, we must average over 54,100 housing units created per year over the next five years, and we need a significantly larger percentage of them built, as starter homes that are affordable and attainable to all Coloradans.

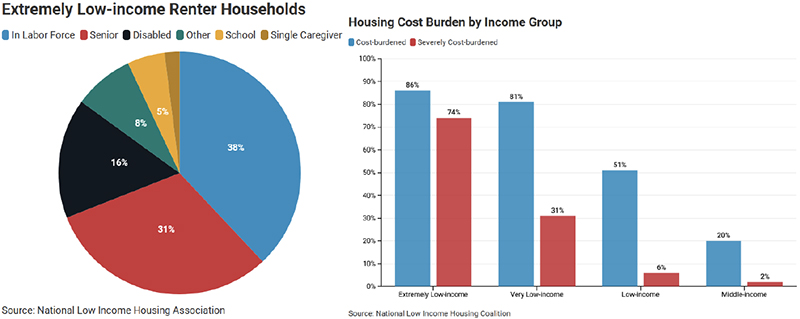

In addition, the National Low Income Housing Coalition details in 2020 Housing Needs by State how the cascading effects of our affordable housing supply shortage impacts our extremely low income (ELI) fellow Coloradans who earn 30% or less of our state’s median income ($28,790 max income for a family of four).[viii] These individuals are hit the hardest, and their housing stability has and remains an immediate concern. With 162,557 ELI Coloradans representing 21% of our state renter households, 74% are extremely rent burdened, spending over 50% of their income on rent. Who are these ELI Coloradans? They are us, they are our senior Coloradans (31%), they are our fellow Coloradans living with disabilities (16%) and many of them are in the workforce (38%). Our fellow ELI Coloradans are more likely to experience food insecurity, delay seeking medical care, and are disproportionately at risk of eviction and homelessness. With every affordable housing unit not created due to our discretionary policies enacted by our decision-making processes, we send a stark message to our ELI Coloradans that their lack of housing stability, the very foundation of a healthy and stable life, is a tradeoff we are willing to concede.

Unless we undergo a radical change in the way we prioritize, invest, facilitate, and conceptualize housing development, starting with an honest conversation based on the facts, and move the conversation from emotions to outcomes, we will experience more of the same punitive outcomes for which we are experiencing today. It can, and will, get worse without deep introspection and a willingness to change. We Coloradans can do tremendous things – inaction is not an option, de-population is not a strategy; it’s a dereliction of our responsibility to our fellow Coloradans. So what policies and processes can we engage to get Colorado on the right trajectory?

Colorado Housing Development Guiding Principles – Our True North

As Terry J. Stevinson Fellows, we have curated a list of the most recommended policies during our stakeholder engagement, and subsequent research for our state and local governments to consider in addition to our own recommended policies. We passionately reiterate the sobering fact that all the tools in the world won’t make a difference if we don’t first change our entire mindset when it comes to housing development and growth. The policies below are only as effective as we allow them to be and any one of them alone will not solve this problem.

Time and time again our stakeholders reiterated the need to introduce a new language for which all Coloradans can utilize to communicate and engage in a shared housing development strategy where local governments, community members, and housing professionals across the continuum come together with the guiding principle of creating more housing units across all categories, but most importantly for sale, affordable starter homes and affordable multifamily housing. To accomplish this, each stakeholder group must be willing to compromise and make tradeoffs. Yes, these tradeoffs are likely to draw concern and opposition from the radical elements within our coalitions, but we have no choice remaining – the current process is not and will not serve the needs of Coloradans. We call on all stakeholders to ask yourself – what is the one element within your control that is a systemic driver of our housing crisis that you are willing to confront and change?

So before we dive into the recommended policies we first respectfully present a set of principles that will guide our future decision making, allowing us to assign values to our decision making analysis, breaking through impasses, via clarity of purpose and thus guide our behaviors when the going gets tough — and it’s always going to be tough — when it comes to housing development.

We call it our Colorado Housing Development Guiding Principles and we see them applying to both creating and preserving deeply affordable housing and heck, all other types of housing development as well. We also acknowledge that we have not included every impactful and viable tool, or identified every initiative. Our scope focused on what stakeholders and our professional experience have identified as root causes—within our control as Coloradans—that if we engage, can unlock the full potential of the plethora of leading housing policies. We have focused on systemic change, not band aids. If we missed a policy that you as a reader love – we probably love it too, except if it’s rent control. Sorry, we are not in love with rent control.

Colorado Housing Development Guiding Principles

1. Let us be honest with ourselves – and do away with binary constructs that distill people into characters. No more “us vs them,” “good vs bad,” NIMBY vs YIMBY. Simply, us as Coloradans, in need of an affordable home.

-

- We must lead all housing conversations with a transparent and honest discussion of the facts rooted in data so that we increase the trust quotient amongst all Coloradans.

2. Let us embrace growth – a vibrant, growing economy, supported by a healthy housing supply, benefits us all; increasing our tax base, sustaining our communities basic needs.

-

- Limiting growth only serves to exasperate the housing crisis – no data exists to suggest otherwise.

3. Let us reform the popular notion that all development, most specifically affordable development at or below 60% AMI, must pay its own way.

-

- We didn’t require this of our greatest generation coming home from WW2 and we shouldn’t for this generation. We simply cannot correct this crisis without this fundamental fact. Local governments must resume paying for infrastructure and offsite improvements for affordable housing development. The pay your own way experiment has failed us – just look at the outcomes.

4. Let us be proportional, equitable, and inclusive.

-

- Public engagement is essential but one’s private property rights do not and should not be allowed to infringe on other citizens private property rights. It is simply not fair to all parties involved. It creates binary high conflict and separates us from accomplishing our mission of creating housing so that all Coloradans can have an affordable home. Engage the public equitability during the master planning process, make decisions, and then adhere to them.

5. Acknowledge that the private market will not create deeply affordable units at the scale required on their own, nor will inclusionary zoning tools alone accomplish this in our current construct.

-

- We must continue to incentivize subsidized affordable housing unit creation at 60% AMI or below with a focus on creating units at or below 50% of AMI.

6. Let us embrace new building methodologies to increase productivity and growth.

-

- Product standardization, such as modularized offsite building, digitized technology such as BIM, and regional local governmental agreements offering building and zoning code reciprocity is our affordable housing salvation.

7. Act with a sense of urgency and purpose.

-

- Every tool, every policy, should be subject to the following litmus test: “will this increase the amount of housing developed, and as such, create greater affordability? Or will it impede it?” If we agree and proclaim that affordable housing is a city and state priority this litmus test will ensure our decisions do so as well.

We’ve set the guiding principles and we all agree on them, yes? Next, we discuss policies we would like decision makers to meaningfully engage, regardless of local control dynamics, as these are of a statewide concern. Just because we’ve always done it one way doesn’t mean we are bound to a failing approach in perpetuity. Let’s give these ideas a chance – what more do we have to lose?

Ideas That Work, If We Let Them as Told To Us By Our Interviewees

We were deeply influenced by Amanda Ripley’s work which encouraged us to “widen the lens” in order to “get people to reveal deeper truths” when getting to the heart of complex issues. By asking curious questions and listening, we were able to elicit honest answers. In response to the broad questions of “what’s working?” and “what’s not working?”, we were able to hear a wide range of policy solutions. But because we wanted to get to the bottom of some of the systemic drivers that have been keeping us in this impasse, we also asked, “what is oversimplified about this issue?” and “is there any part of the other side’s position that makes sense to you?” The answers were surprisingly consistent.

We curated these policy options for policymakers to consider that come from a broad range of housing professionals in our state; the people doing the work. Some of these ideas we’ve seen in play in other cities and so we dug into how those worked and what could work differently in our state.

IDEA 1: Prioritize the use of public property for the development of mixed-use affordable housing

- Harness the intrinsic strengths of Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) via their Powers of Authority to partner with city and county governments, transit authorities, and school districts via Intergovernmental Agreements to facilitate the transfer of government owned lands as a donation for the development of affordable housing communities. Affordable housing covenants ensure that PHAs utilize the land donated in a manner consistent with local affordable housing priorities, dictate affordability requirements, contain development milestones for use of the donated land, and provide transparency for the public to evaluate outcomes. Colorado has a rich fabric of sophisticated Public Housing Authorities who own, operate and develop affordable housing communities – we should expand our partnerships to facilitate affordable housing creation.

- Local Housing Solutions, a non-partisan “one-stop housing policy platform” developed by the Furman Center at NYU and ABT Associates highlights national examples of this in action.[ix] While we have examples in both Adams and Boulder Counties, we fellows see this as an underutilized approach that is ready to be scaled across the state at a significantly higher level than we have experienced to date.

IDEA 2: Prioritize homes over parking spaces and create greater “use by right” zoning overlays.

This idea captures the following three policies from The Colorado Housing Affordability Project (CHAP), a collaborative of land use, planning, law, economics, and real estate professionals who have harnessed their collective years of experience to address root causes impacting housing affordability in Colorado.[x] As vested professionals, they have created a platform of land use policy reforms focused on increasing the creation of affordable housing in Colorado. Their approach specifically addresses the barriers that zoning presents to the goal of creating affordable housing, with a bipartisan, local control focused approach built upon the following principles: no tax increases, no incremental funding requirements from state and local budgets, application only in Colorado counties of 50,000 residents or more most impacted by the affordability shortage (15 total) and in their words “make a big difference in the ability of the market to deliver affordable units.” In our conversations with the CHAP collaborative, it is our understanding that they are further analyzing the potential impact of their recommendations and expect to update their platform in the near future. We are eager to review their updated findings and we encourage local and state leaders do as well.

- In counties with more than 50,000 residents, reduce minimum vehicle parking requirements by 50% for any deed-restricted affordable housing units.

- As cited by CHAP, a multitude of studies detail the staggering costs parking requirements place on housing development, reducing the amount of units created by reducing the land available on a site to place the housing in order to make way for parking, causing the remaining units developed to be more expensive.[xi]

- Creating and maintaining parking is far more expensive than folks realize with costs for surface parking between $5K to $10K per stall and for garage parking (structured parking to use development lingo) can cost between $25K to $50K per stall!

- A 2016 study found that requiring one parking space per unit increases the cost of development by 12.5% and requiring two increases the cost of development by 25%.

- As cited by CHAP, a multitude of studies detail the staggering costs parking requirements place on housing development, reducing the amount of units created by reducing the land available on a site to place the housing in order to make way for parking, causing the remaining units developed to be more expensive.[xi]

- In every city or town in a county with more than 50,000 residents, allow by right a minimum of 25 dwelling units per acre on all properties within one-eighth of a mile of any fixed transit station.

- Zoning can facilitate housing development or, as happens far too often, can hinder or outright eliminate the creation of housing development. It is quite simply the most important element within our control as Coloradans – our zoning policies reflect the decisions we make and the outcomes are ours to own. If we truly believe that we have a housing affordability crisis we must tackle the highly emotional nature of zoning directly, no matter how challenging the initiatives will be.

- This is a proposal built on compromise and we fellows encourage local jurisdictions to consider far greater density allowances to accomplish the goal of creating greater housing supply.

- In every city or town in a county with more than 50,000 residents, allow by right a minimum of 10 dwelling units per acre in at least 10% of the land area of the city or town.

- As described by the CHAP collaborative “Ten dwelling units per acre is roughly equivalent to a two-story attached townhouse or row house community. Townhouses and row houses—which fall within the category of “missing middle” housing—are important housing types in every community, as these types of homes are often “starter homes” for young families or places where older communities choose to “downsize” to.[xii] This proposal would require every city or town in larger counties to zone at least 10% of their land area for these types of housing, ensuring that more affordable forms of housing are available throughout Colorado’s growing urban, suburban, and resort areas. This proposal also ensures that every community contributes to providing housing for a diverse group of renters or buyers.”

- Here we see another policy focused on compromise as the density and percentage of land areas can be expanded to address the shortage of single-family affordable housing.

- We fellows also look forward to how CHAP addresses where the percentage of land is to be located as we cannot ignore the historical lessons of redlining which segregated affordable communities, permitting them in locations adjacent to industrial uses, away from amenities that promote economic and health wellbeing.[xiii]

Ok… So Hold Up? Are any other States Doing This? Learning from Massachusetts’ Chapter 40B

In reviewing CHAP’s proposal for allowing by right zoning in at least 10% of the municipality’s land we could not help but think, why 10%? Why not 5% or even 15%, 25%? What’s the right number? In searching for the answer, we turned to the Massachusetts Comprehensive Permit Act, or Chapter 40B of the Massachusetts General Laws which was enacted in 1969. Chapter 40B allows developers of affordable housing to override certain aspects of municipal zoning requirements where a municipality has less than 10% of its housing stock affordable. The law reduces barriers to affordable housing production by granting local zoning boards of appeals (ZBAs) the authority to approve housing developments if 20 to 25 percent of the units remain affordable for a period of 30 years to households with incomes at or below 80 percent AMI. Chapter 40B also simplified the permitting process for developers by allowing them to apply to a single authority: the local ZBA. Chapter 40B sets the process timeframe for approval. The public hearing process must start within 30 days of the application submission, and be completed within 6 months. After the public hearing process ends, the ZBA must issue a decision within 40 days. Failure to comply with either statutory timeline results in default granting of the permit.

Appeal of denials go to the state Housing Appeals Committee (HAC) if the municipality does not meet the 10% affordable threshold. Once the 10% threshold has been met, developers may still apply for a permit, but they cannot appeal the decision. The HAC has the authority to overturn a local ruling unless the development poses a risk to health and safety of the community. The burden of proof is on the local zoning board to demonstrate that there is a valid health, safety, environmental, design, open space, or other local concern which outweighs the regional housing need.[xiv] This is an important departure from other legal precedent in other states where there is a presumptive validity to local authorities in zoning cases.

The passage of 40B was marked by support from liberal legislators and housing activists amidst the inner city decline and unrest of the 1960s. The bill passed narrowly in the Democratically controlled House and Senate of the Massachusetts legislature. The vote was not along party lines, however, garnering support from suburban Republicans. It was signed by Republican Governor Sargent in August of 1969. While considered partisan at the time due Democrat leaders in the House and Senate using political muscle to line up the winning votes, such a bipartisan vote count does not seem achievable these days.

Chapter 40B broke new ground in the battle of zoning reform and effectively set a goal for the state, or “fair share quota” of affordable housing needs. However, the impact was initially limited. Originally, the vast majority of properties were 100 percent affordable rental units with a direct source of funding from public housing or Section 8 funding. In 1990, Massachusetts created the Local Initiative Program (LIP), which allows developers to work with municipalities with state technical assistance serving as the requisite source of subsidy for affordable units. Now, the majority of Chapter 40B housing built is through the LIP process with private developers building the minimum percentage of affordable units required under Chapter 40B. Given this dynamic, properties built under Chapter 40B are mixed-income. Over the last 50 years, the program has been responsible for creating more affordable housing than any other program in Massachusetts, garnering the attention of other states who are experiencing housing crises.

There are several factors that make a Chapter 40B type legislation attractive given our current housing crisis. We find the affordable housing goal to be a viable option as opposed to a 10% overlay because it provides more options for development. The fact of the matter is that use by right authorization is needed to jump start building in our communities along the entire continuum of housing. Tying it to affordability is one-way communities can ensure that affordable units are being built in this housing shortage. Any legislation would 1) need to address the appeals process as well and make the burden of proof on the local zoning board to demonstrate that the refusal was due to a health or safety concern that outweighs the housing need, 2) provide clear statutory timeframes for permitting which if not met, would allow for automatic approval, and 3) require specific language that legislation applies to home rule municipalities.

IDEA 3: Unlock Large and Non-Traditional Sites for Housing Development – (E.g. Malls and Large Retail Sites)

- Create Use by Right Zoning Overlays via inclusion in local government master plans to facilitate redevelopment without then again requiring local government approval.

- It is no secret that shopping malls throughout America are struggling; they were pre-pandemic and will continue to do so moving forward. Consumer trends have changed and so has the appeal of large malls with acres of empty parking lots leaving communities to live with these underutilized places. Many malls have large vacancy rates with anchor tenants vacating due to bankruptcy. Often the sites are not maintained creating additional tension and concerns. We see this as a mutually beneficial solution that local governments and communities can deploy to unlock land for housing development. Local governments can preface eligibility based on the affordable housing goals of their community, but we recommend mixed income communities with market rate and a meaningful percentage of deeply affordable units set at or below 50% of AMI.

IDEA 4: Utilize Community Land Trusts to Create and Maintain Affordable Home Ownership

- Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are a shared equity solution, offering home ownership for income qualified, home ownership ready community members that, due to the market forces outside of their control, could not qualify for a home otherwise. In Colorado, we have outstanding Community Land Trusts that we fellows cite as examples for Colorado leaders to engage for the creation of CLTs in their community.

- CLTs provide below market home ownership opportunities through a land lease model

- CLTs prevent displacement, providing the financial security and wealth building opportunities of home ownership

- CLT’s facilitate community strength through reduced foreclosures and pride of ownershipCLT’s are the embodiment of affordable housing preservation ensuring that resale homes remain affordable to future income qualified owners

IDEA 5: Allow for Accessory Dwelling Units – An Important Step Towards Standardization

- Colorado or individual municipalities should implement policies that encourage, expedite, and facilitate the creation of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) for property owners.

- While not the panacea, and indeed, ADUs are unlikely to make a significant dent in our housing deficit, the creation of ADUs allows homeowners to increase their property values, be revenue generating, and adds to the housing stock in a community. Additionally, it allows seniors to retire in place or on their own property since the ability to downsize in our communities is currently severely restricted. By creating a transparent process with uniform or pre-approved design standards and expedited permitting, jurisdictions can meet ADU goals in their communities efficiently.

A useful case to review is California’s ADU legislation. A 2016 McKinsey study identified the need for 3.5 million new homes in California by 2025.[xv] Indeed, Governor Newsom made it one of his campaign promises in 2018, which equates to approximately 500,000 new units a year. Part of the strategy to boost housing production was to increase production of accessory dwelling units. ADUs can be created by taking space from an existing building, adding to an existing structure, or constructing standalone detached buildings. ADUs are a low-cost and readily implementable approach to infill development, particularly in high-cost cities characterized by little to no vacant land. Typically, an assortment of barriers including land use and zoning regulations, permitting bureaucracy, and high construction costs restrict the widespread development of ADUs in a state. With 75% of California residential land zoned for single-family, the extended permissibility of ADU’s is an important tool in infill development which can help affordable housing supply as well as add value and potential rental income to the homeowner.

Prior to Governor Newsom taking office, the California legislature passed several state laws in 2016 that permit the building of accessory dwelling units (ADUs), also called granny flats, in-law units, and casitas, on a single-family zoned property.[xvi]His first year in office, additional ADU legislation was passed that addressed barriers to building including restricting local jurisdictions’ permitting criteria, streamlining and expediting approval, and eliminating local agencies’ ability to require owner-occupancy for five years. Additional changes to ADU laws effective January 1, 2021, further reduced barriers such as owner occupancy, overriding HOA restrictions, and expanded capacity to accommodate the development of ADUs and junior accessory dwelling units[xvii]. Additional provisions included modifying fees from utilities such as special districts and water corporations, limited exemptions or reductions in impact fees, and reduced parking requirements. The state provides grants and financial incentives for the production of ADUs. These provisions further incentivize and promote the creation of ADUs in order to alleviate housing affordability for very low, low, and moderate income households.

In California, nearly 75% of residential land is zoned for single-family housing.[xviii] By allowing a homeowner to build up to two additional units on a single-family zoned property, and eliminating local governments’ discretion to deny these projects or impose additional conditions on approval, California has effectively eliminated single-family zoning. Yet, even with additional incentives to build and retooling by the state legislature over subsequent years, ADUs have not reached their desired potential in California. Between 2018 and 2019, permits increased from 5,911 to almost 15,571.[xix] During that same period, ADU completions more than tripled from 1,984 to 6,668.

However, challenges to scaling ADU development remain, particularly in the area of financing. Constructing ADU in California remains prohibitively expensive for many. The Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley found that the average ADU cost in California is on average $167,000 with large differences in regions based on labor costs. In fact, they found that ADU construction in the Bay Area can exceed $800 per square foot, equaling $400,000 for a 500 square foot ADU. Most of the homeowners taking advantage of the new ADU laws were in affluent areas with homeowners with high equity; suggesting a need for better financing tools for low-and moderate-income homeowners.

Unlike California, the state of Colorado has not made any statewide moves to encourage build by right development of ADUs to property owners and has left it up to individual zoning and permitting. Several pilot programs are underway to increase the production of ADUs in various cities. Like other states that are struggling with ADU production, the ability for an individual to navigate the sometimes wrought process of development is one of the main factors that inhibits ADU production. In Denver a collaborative in partnership with the Denver Housing Authority provides a one-stop shop to ADUs. The pilot program assists homeowners with developing ADUs on their property by providing design, entitlement, housing counseling, financing referrals, and construction services. As homeowners seek to take advantage of home equity, programs similar to this which looks at barriers to development can assist in the creation of more ADUs in the state. A valid, although not complete, solution to our housing deficit, ADUS allow property owners to add value to their property, allows seniors and others to age in place, and reduces sprawl. Prior to any build by right statewide legislation, infrastructure needs, design standards, parking requirements, and fees should be reviewed and streamlined in order to incentivize the creation of ADUs and alleviate housing affordability.

What Is The Hot Topic Of The Moment That Is Leading Us Astray? Rabbit Holes Anyone?

The entire nation is facing a housing shortage. So, while the conversation in Colorado has been ongoing, similar conversations are happening around the United States. But we know that housing is highly localized. What’s working in San Diego, may not necessarily work in Denver. And what’s not working in Bozeman, may possibly work in Grand Junction. But we wanted to get the conversation going. In an effort to “widen the lens” we asked, “what are the rabbit hole policy ideas?” and “are there any policy ideas that are overtaking the conversation in a nonproductive way?” We were not surprised at some of the answers, but we delved into the details to uncover if we could find the root of such a contradiction. Here’s what we found:

The Elimination of Single-Family Zoning, Panacea, Rabbit Hole or Possibly Much Ado about Nothing?

Much has been made about the elimination of single-family zoning. In 2019, the city council of Minneapolis approved ending single-family zoning throughout its jurisdiction by allowing duplexes and triplexes on all single-family lots. The much-lauded move was praised as “groundbreaking” and “historic” by the national media and liberal policy groups, yet when we asked our interviewees “what policy, be it recent or not, is leading us astray, all hat, no cattle,” time and time again the elimination of single-family zoning was the response. It is still too early to make a determination on long-term effectiveness of Minneapolis’ policy change, however, thus far it has not proved to be the boon that many hoped, either for the missing middle or affordable housing.