Introduction

If passed by voters this fall, Denver’s citizen initiated Ordinance 305, “No Eviction Without Representation” would levy a new tax on landlords, of $75 per residential rental unit, to fund universal tenant legal representation for those facing an eviction or threat of eviction in the city. The measure requires the City of Denver to “establish, run and fully fund a program to provide legal representation as a matter of right for all tenants within the city who face a covered proceeding to the greatest extent possible based on the program’s funding.”

In addition, the initiative creates a city-wide tenant committee, which will be comprised of 7 members who are current tenants within the city. Committee members would be paid a yearly $1,000 stipend and be responsible for overseeing the effectiveness of the program.

Key Findings

The tax increase in the measure likely far exceeds what could reasonably be spent to cover the costs for universal eviction defense.

-

- The medium estimates across our three scenarios for annual levels of evictions, showed the program would only cost between 17% and 35% of tax revenue collected. This would leave an excess of funds between $9.9M and $7.8M of an approximately $12M tax increase.

- The measure does not include any provisions to reduce the tax on landlords to ensure that the total taxes collected remains in-line with costs. The City Council may elect to transfer excess funds to spend on other purposes outside of what is prescribed in the Ordinance measure, or the program administrators may develop ways to spend more of the funds related to eviction defense in less meaningful ways.

- Both the direct tax increase, and the increased legal costs to landlords from higher rates of tenant representation in eviction proceedings, will primarily be passed on to renters in the form of increased rents, larger security deposits or some other means. These additional pressures on rent come at the same time as rents have skyrocketed in past 12 months.

- The measure would institute a universal right to legal representation and makes no distinction between tenants who cannot afford an attorney and those who can. Additionally, the measure does not place limitations on the type of eviction covered and includes “just cause” evictions where the tenant has not paid rent or violated other lease provisions.

- Tenants represented by lawyers do have far more favorable outcomes however, those outcomes do not discharge a tenant’s monetary obligations under their lease. Federal, state, and local programs already exist for eviction related support funding in the form of rent and utility financial support and legal services. Though the funding for those programs will not change, the coverage of free legal services largely replaces existing funding, rather than complements it.

Fiscal and budgetary Impacts

Who Is the Tax Collected From?

The new tax will be collected from residential landlords in the form of an annual $75 excise tax per unit. This tax will be applied to all individual, non-exempt, residential properties leased by the landlord per year. Exemptions for the tax are narrow. Only rental units in which the landlord, or members of their family, are currently occupying may be exempted. The tax is to be adjusted for inflation annually.

How much does the new tax raise?

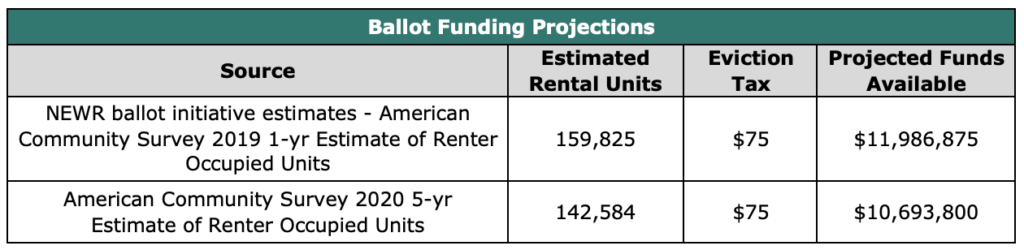

The fiscal estimate of the measure to appear before voters indicated that the new tax would collect $11,986,875 in its first full year. This comes from the 1-year 2019 American Community Survey which estimates that there are 159,825 rental units in Denver. According to the American Community Survey’s (ACS) 2020 5-year estimates, there are 142,584 rental units in Denver[i] which would amount to $10,693,800 in available funding.

How much will get spent?

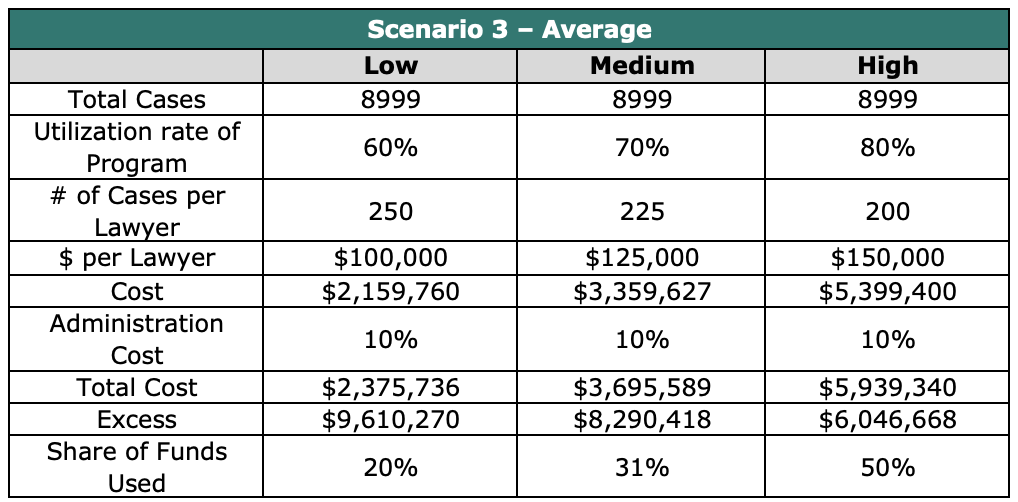

Between 2008 and 2021, there was an average of 7,882 evictions per year. However, as the table below shows, there were significant drops in the years of 2008, 2020 and 2021. These years stand out as they covered a period of significant economic decline and a federal and state eviction moratorium during the pandemic. After removing the down years, there was an average of 8,999 evictions between 2009 and 2019 with a range of between 7,907 and 10,241.

Given the lack of comprehensive data on eviction proceedings and the uncertainty of the utilization and cost of legal services, the following scenarios capture a range of the extent to which the revenue collected from the new tax will cover those that seek legal support in eviction proceedings in Denver. The scenario parameters include:

- Coverage from existing state and federal funds

- Utilization rate

- Cases per Lawyer

- Cost per lawyer

Coverage from Existing State and Federal Funds

The Ordinance states that “the city shall have no obligation to provide legal services under this Section where a state or federal program provide full scope legal representation to a tenant facing eviction proceedings as a matter of right.”

Currently, there are several resources available to renters’ facing eviction in Denver to receive free legal services although there currently is no requirement for legal representation as a “matter of right”.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) – Even prior to the historic events of the pandemic where the federal government appropriated $46.55 billion in emergency rental assistance (through the Department of the Treasury) for households unable to pay their rent, the federal government allows funding through several programs to be utilized for eviction prevention, including for the provision of legal assistance in eviction proceedings, often called eviction diversion programs. Programs aim to help renters stay in their homes and provide support services well before an eviction is filed since legal defense programs are limited to tenants who are already facing eviction. By assisting renters early on, both the landlord and tenant can avoid the costly and adverse outcomes of an eviction procedure. Funding from HUD focuses on the spectrum of activities that promote eviction diversion:

- Housing counseling grants are just one of many federal programs that can be utilized for financial literacy programs. Between 2016-2022, Colorado received over $3.5 million in grant funds that can be targeted toward eviction prevention, including for legal defense.

- Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) is one of the largest and most flexible programs run by HUD. It provides annual grants on a formula basis to states, cities and counties who determine the utilization of the funds based on consolidated planning done at the community level. Denver receives its own CDBG allocation, an average of $6.7 million annually toward its priorities, including eviction diversion or rental assistance.[ii]

- During the pandemic, supplemental funding was allocated to states and cities for emergency rental assistance in the first supplemental funding package. The CARES Act CDBG-CV funding was an effective vehicle for emergency rental assistance given fund recipients were already familiar with the CDBG program and the compliance requirements. Denver received $4 million in CDBG-CV funds to use for its priorities, including eviction diversion or rental assistance.[iii]

State Eviction Legal Defense Fund – State legislation in 2019 established a statewide fund to award grants to non-profits, to “expand availability of legal assistance for low-income persons who experience an eviction or an immediate risk of an eviction”[iv]. This program awarded $1.94 million in grants for nonprofit legal organizations in the state for both FY 2022 and FY 2023.

City of Denver- Denver’s Temporary Rental and Utility Assistance (TRUA) program is a housing stability program for residents at risk of involuntary displacement. TRUA provides rent and utility support for households earning 80% of the area median income that address critical and immediate needs including rental assistance and legal assistance for potential eviction. In 2021, Denver City Council approved the use of $1.1 million in funds expected to cover the legal expenses of 1,800 households over a three-year period[v]. The Department of Housing Stability (HOST) provides fundings for legal representation in eviction proceedings for renters in Denver at or below 80% of the area median income[vi].

Though these resources currently exist, the cost scenarios presented below do not assume that any evictions cases in Denver would be covered by existing state or federal funds if the measure passes.

Utilization Rate

Average expenditures per case for free tenant legal representation in San Francisco, which passed a similar measure “No Eviction Without Representation Act of 2018”, were, on average, $300 per case including a 15% overhead charge[vii]. While Denver’s costs are likely to be similar, we’ve included a range of potential costs to show how the ballot’s budget would be impacted.

To better understand how many eligible Denver tenants would use the program and the subsequent strain on the contracted free legal service providers, we’ve analyzed the utilization rate of fully implemented right to counsel programs currently operating in both San Francisco and New York. In San Francisco, 67% of tenants facing eviction received full-scope legal representation and New York reported a similar 71% of tenants obtaining free representation through their respective program[viii].

Cost per Lawyer

In order to estimate legal costs for the program, we gathered the salary range for both Colorado Legal Services and the Colorado Poverty Law Project, the predominant providers of legal services for low to moderate income individuals. Both organizations have previously worked to provide free eviction legal defense through existing programs. While the measure does not require the use of a nonprofit service providers, these organizations could be contracted to expand the scope of this defense to be universally available. Their salary ranges were similar: $59,000-$99,000 for CLS and $65,000-$85,000 for CPLP[ix]. We estimate these salaries to be slightly inflated to reflect the caseload and work requirements expected.

Cases per Lawyer

According to Denver’s Housing Stability Director, attorneys currently tasked with providing free eviction legal defense under existing programs operate with a caseload of around 250 cases per year[x]. Colorado Legal Services estimates their attorney caseload to be 200+ cases per year when dealing with evictions[xi]. We’ve included a range of caseloads within our model to better estimate this cost.

Scenarios

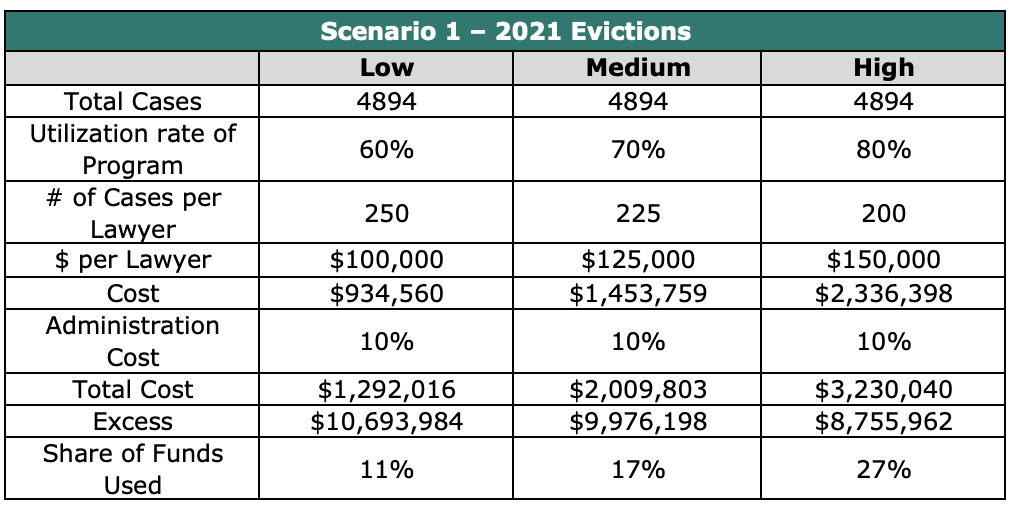

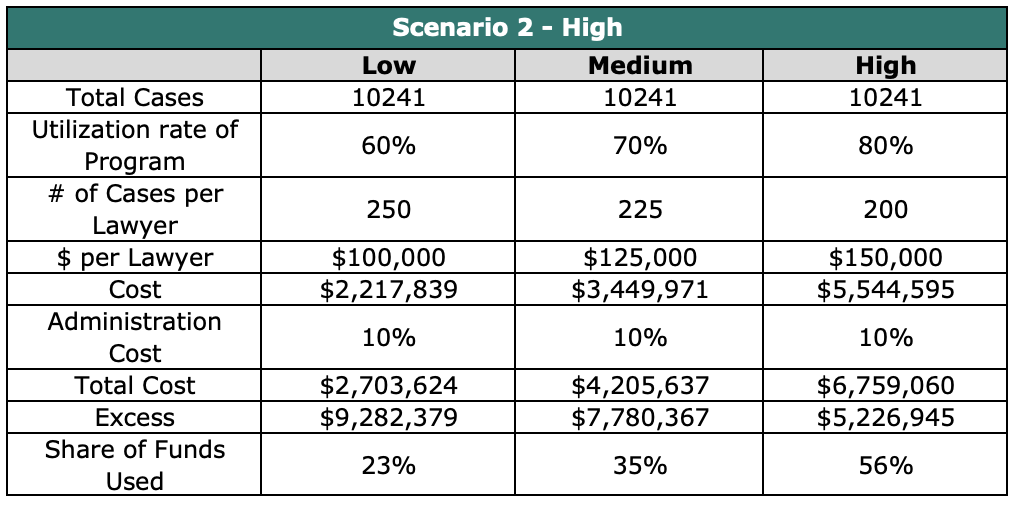

Using the various parameters listed above, the following table shows the potential cost, and level of excess funds, under three scenarios, each with a low, medium and high-cost estimate.

Scenario 1 – What if there were 4,894 evictions, the same number of evictions as there were in 2021?

Scenario 2 – What if there were 10,241 evictions, the highest level of evictions as seen in 2010?

Scenario 3 – What if there were the 8,811 evictions, the average amount between 2009 and 2019?

What happens to funds that don’t get spent?

According to the initiative, any unspent funds are to be retained by the program as a reserve to be used in the future. However, given the scenarios on the use of the funds, it is likely the program could become chronically overfunded.

Should this occur there are two likely scenarios:

- The City will transfer funds towards other city spending. In the case, the new tax acts as a general tax increase, rather than a new tax specific to universal access to eviction defense.

- The program will make attempts to increase the use of the funds by reaching more tenants or by increasing the level of legal coverage. It is likely that in this case, the new tenants who would be reached would benefit less from legal support and it will only further increase the legal costs to landlords with limited benefits to tenants.

Public Savings from Increased Tenant Legal Support

Existing federal and state eviction diversion programs seek to keep people housed by finding solutions to disputes between renters and landlords early in the process to avoid court mandated evictions. Once a court has issued a judgment in an eviction case, it can have long-lasting adverse impacts on the tenant. Eviction diversion programs include a mix of programs such as rental assistance, mediation, legal representation, and other resources and support services.

Research indicates that through increased legal services for those facing evictions, there are significant reductions in public expenses elsewhere through lower shelter costs, healthcare, job stability, regular school attendance, and other social support programs. Analysis of the city of Baltimore found that a right to counsel program for tenants facing eviction would generate $35.6 million in savings for an investment of $5.7 million, or just over $6 saved for every dollar spent[xii]. Similarly in Philadelphia, estimates place the savings for the city at $12 for every dollar invested into legal representation[xiii]. The study focused on Baltimore which subsequently implemented a right to counsel program funded by HUD pandemic supplemental funding. While the program does not include income limitations it does give priority based on income level and the program is subject to continued availability of funding. Data is not yet available on the impact of the program although an annual written report is required.

Though the research suggests these savings can be net positive to public budgets, this measure relies on a new tax to support the eviction fund and does not lower taxes elsewhere or reallocate existing funds. In contrast, the Denver measure focuses solely on providing legal representation to tenants much later in the process, and usually only delays an inevitable eviction, whereas a more holistic diversion program provides supports early in the process and can often prevent an eviction from being filed in the first place, saving both the tenant and the landlord the stressful and costly process of a court proceeding.

The ballot measure is part of a right to counsel movement that has been implemented in fifteen cities and three states over the last several years. The first city to adopt a right to counsel was New York City in 2017. Unlike the Denver measure, the New York City program is not a universal right; it includes income eligibility limits as well as non-profit provider requirements. The Denver measure is more similar to San Francisco’s right to counsel measure which provides a universal right to counsel without limitations for income, types of evictions, or types of service providers. However, unlike the Denver measure, the San Francisco ballot measure posed to voters did not include a separate source of funding. The San Francisco comptroller’s independent study prior to adoption estimated the program would cost taxpayers between $4.2 million and $5.6 million in the first year of implementation, beginning June 2019 but once adopted, the program requested doubled the estimate to $9.6 million in FY 2019-2020, prior to the pandemic.

The right to counsel movement for tenants is relatively new and programs newly implemented do not have measurable metrics to judge effectiveness. Most jurisdictions have funded this requirement with federal pandemic relief dollars or other HUD funding such as Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) or Housing Counseling grants, or from general revenue allocations. The Boulder, CO measure, adopted in 2020, is the only such measure similar to the Denver ballot measure where a $75 per unit excise tax is levied on the landlord to fund the program, however, the Boulder program allows for the funds to be used for rental assistance in addition to legal services.

The resulting program, the Eviction Prevention and Rental Assistance Services (EPRAS), was implemented in January 2021. In its first full year of operation, Boulder officials reported the tax was expected to raise $1.9 million in the first year.[xiv] The program was contacted by 390 tenants to access services before or at court and referred 204 tenants to an outside legal services nonprofit who received a grant to implement the program. In 2021, EPRAS was able to prevent 68 of 88 City of Boulder cases observed at eviction court.

The New Tax and Increased Landlord Legal Fees Get Passed on to Renters

Though the monthly tax of $6.25 ($75/year) to fund the program is collected from landlords, in all likelihood this tax will be passed on to renters upon renewal of a lease. According to RentCafe, a nationwide internet listing service, as of July 2022, 1 percent of apartment rent per month in Denver falls between $701 and $1,000, 21% are between $1,001 and $1,500, 39% are between $1,501 and $2,000 and 39% are greater than $2000[xv]. This regressive tax will effectively raise rents by 0.89 percent for the lowest cost rentals at a time when the lowest income segment of the population is being squeezed by the unavailability of low cast rental housing and high inflation.

The Colorado eviction process can take anywhere from two weeks to four months depending on whether the eviction is for illegal activity, or another type of eviction[xvi]. If the tenant files an answer with the court, the process could take longer. Having legal representation increases the probability that an answer will be filed with the court and thus the length of time the tenant can remain on the property while the eviction process proceeds. Lengthier eviction processes increase the cost to landlords via increased legal fees and potentially lost income in the case where the tenant has stopped paying rent.

According to data collected by TransUnion SmartMove, total eviction expenses for property managers average $3,500[xvii]. Despite a writ of restitution requiring the tenant to pay for filing fees and past due rent, realistically, the likelihood of the landlord receiving full restitution are low. According to the American Collectors Association, there is only a 17% success rate on the average debt collection[xviii].

In response to increased legal expenses, landlords will require higher rents, larger security deposits, the purchase of unpaid rent insurance, or all three, to offset potential lost revenue going forward. Data shows that landlords are extremely effective at passing on excess costs to their tenants with an estimated 80%-90% of increased costs for the landlord being absorbed through rent increases[xix]. The impact on tenants is an increase in monthly rental expenses as the landlord has no incentive to incur the full cost of these actions.

The less discussed aspect of these programs is the landlord who has their own obligations to meet such as mortgage payments, property taxes, and building upkeep and repairs. According to the 2018 Census data, most rental properties are owned by individuals who typically own just one or two properties. Individual investors own about 71.6 percent of properties nationally which means small business owners comprise the largest group of landlords. In the Denver Metro Area, the Colorado Apartment Association estimates 70 percent of rental properties are seven units or less. Therefore, focusing solely on the tenant in an eviction proceeding is injecting instability in the housing market as a whole as landlords try to meet their own obligations.

Universal Right

The right to counsel is a right guaranteed to criminal defendants by the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution. Evictions are civil proceedings are rooted in contract and property law. States have specific landlord-tenant laws that protect the interests of both the renter and the landlord. There is no corresponding right to counsel for civil cases in the Constitution and the expansion of this right for eviction proceedings has become a recent push in several communities across the United States. However, where enacted, either through legislative action, ordinance, or in limited cases, ballot measure, most programs in fact limit representation to low-income tenants and/or tailor the scope of program to evictions based on discriminatory or retaliatory actions, or other no-fault evictions. Additionally, programs usually are subject to funding limitations as well as a requirement that legal services are provided by non-profit providers to curb abuse of the system by unscrupulous attorneys who can extend proceedings to increase their own profits without regard to the legitimacy of the case. This measure specifically allows the use of private law firms and private attorneys.

No income limits are included in the ordinance, therefore the program would provide services regardless of the tenant’s ability to pay. The measure does not limit the type of eviction and so includes evictions proceeding where there is just cause for eviction. Colorado law already provides that landlords must have legal cause in order to terminate a lease. Legal causes include failure to pay rent or other violations of the rental agreement, as well as criminal or drug related activity at the property. Even if the landlord has cause for termination, the tenant may still fight the eviction with a valid defense such as failure to maintain the unit, retaliation, or discrimination.

While eviction proceedings can occur for multiple reasons, the leading cause is related to financial losses incurred by the landlord, primarily related to missing rental payments. Tenant evictions are a reality of our housing rental market when obligations under the lease, or contract, are broken. “Just cause” eviction policies support housing stability as it provides the reasons by which a landlord may evict a tenant. Evictions are disruptive, expensive, and time consuming for both the tenant and landlord. As such, publicly funded programs exist to support renters facing financial hardship, particularly if based on loss of income or inability to pay because of pandemic economic pressures. While every renter faces a different situation, substantial funding exists across a range of city, state and federal programs, aimed directly at avoiding eviction proceedings for both just cause, where material non-compliance with terms of the lease lead to an eviction, as well as unjust cause evictions for reasons such as discrimination or retaliation. These eviction diversion programs are aimed at keeping people in their homes and therefore focus on interventions before cases go to court, where an adverse judgment against a tenant can have long-term ramifications. Additionally, early mitigation programs such as mediation can benefit both the landlord and tenant by avoiding the expense and burden of litigation and working toward keeping the tenant in their home and allowing the landlord to recoup rent money.

Measure Oversight

To oversee the program, the measure would create the “Tenant’s Legal Services and Assistance Coordinator” to be chosen from within the City of Denver’s internal staff. The coordinator would report directly to the mayor and be responsible for contracting and supervising the legal service providers who are tasked with providing legal services.

In addition, the coordinator will also be responsible for creating a report to be released annually by September 1st to both the public and mayor’s office detailing the program’s effectiveness.

Based on this reporting, and other data expected to be collected, City Council should take action to “right-size” the program based on actual need. This would take the form of reducing the size of the tax increase along with revisiting eligibility requirements. Other jurisdictions with right to counsel laws, often restrict who can access a lawyer through some income threshold, or by limiting the types of evictions that can access a lawyer such as only those related to property damage, or behavioral issues. Given a large majority of evictions are related to late and missed payments this could significantly reduce the taxpayer and landlord burden.

Allowing for significant excess funds will lead to larger unintended consequences through higher costs to landlords, or use of funds not authorized by the voters.

Conclusion

If passed, Ordinance 305 would substantially increase the number of tenants receiving legal representation in eviction proceedings as evidenced by similar programs. Money spent towards eviction defense benefits the city through lower costs associated with homelessness, healthcare, and other societal expenses. However, the initiative will likely be overfunded for its purpose. Funding for the program will be collected from landlords, who will in turn pass off a large portion of these costs, and their additional legal expenses, onto their tenants resulting in higher rent costs and larger security deposits ultimately leading to a more unaffordable housing market and housing instability. In addition, the city of Denver has several resources available to renters in the form of rent and utility payment assistance, as well as free legal defense in eviction proceedings for those who qualify.

These existing community-based programs and safety nets are a more tailored and collaborative approach that focuses on those who have a genuine need. Designing a new program that helps renters without hurting landlords is difficult given most landlords are individuals who have their own mortgage and property tax obligations. At a time when rents are skyrocketing and housing deficits are impacting the availability of rental units, the ordinance measure only will increase the rental costs for tenants as well as administrative costs for landlords. Additionally creating a new program with a new infrastructure when supports already exist is a wasteful and inefficient use of funding. The measure’s over- estimating of fund needed does not take into consideration other existing programs, nor provide a rational estimate of costs to provide these supports.

© 2022 Common Sense Institute

[i] Table B25129: TENURE BY YEAR HOUSEHOLDER… – Census Bureau Table

[ii] https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/cdbg-state/

[iii] https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/budget/fy20

[iv] https://www.courts.state.co.us/Administration/Unit.cfm?Unit=eldfgp

[v] Denver gives initial approval for $1.1 million for low-income eviction legal defense fund – Colorado Newsline

[vi] Eviction & Foreclosure Assistance – City and County of Denver (denvergov.org)

[vii] Microsoft PowerPoint – Brian MOHCD TRC Hearing Presentation (civilrighttocounsel.org)

[viii] 2021 Universal Access Cover only 8.5×11 (nyc.gov)

[ix] Careers at Colorado Legal Services – CLS, Staff Attorney- Housing and Eviction at Colorado Poverty Law Project (gusto.com)

[x] Denver gives initial approval for $1.1 million for low-income eviction legal defense fund – Colorado Newsline

[xi] Microsoft Word – Document1 (amazonaws.com)

[xiii] Cost-Benefit Analysis for Philadelphia Right to Counsel | Stout

[xiv] City of Boulder Releases its First Eviction Prevention and Rental Assistance Services Report | City of Boulder (bouldercolorado.gov)

[xv] https://www.rentcafe.com/average-rent-market-trends/us/co/denver/

[xvi] Colorado Eviction Process (2022): Grounds, Steps & Timeline (ipropertymanagement.com)

[xvii] https://www.mysmartmove.com/SmartMove/blog/true-cost-eviction.page

[xviii] ACA International Benchmark Survey.

[xix] Can Landlords really pass on higher property taxes to tenants? – Center for Real Estate Center for Real Estate (mit.edu)